Introduction

It was eighteenth-century tourists seeking the Picturesque who promoted perceptions of sui generis Eryri (Snowdonia) through their writings and paintings, framing it as inspiring horror and pleasure. Landscape remains a concept tied to the visual.1 Historic framings of Eryri perpetuate ideologies and ambivalences that have hampered, and could continue to hamper, the much-needed landscape change and local collaboration required to tackle today’s multiple crises. It is increasingly recognised that people’s knowledge of the past, including changes in land use, impacts their understandings of, and preferences for, current and future landscape change.2 Eryri’s landscape has been studied extensively over the past century by ecologists and geologists.3 However, there has been insufficient study of how public and landscape decision-makers’ perceptions and expectations interrelate and inform change within the park.

Eryri is the largest national park in Wales, covering 2,130 km2 of northwest Wales (Figure 1). In the public consciousness, it is perceived as sublime: an unspoilt landscape which shelters significant ecology and cultural heritage.4 Proof of this are the layerings of designations, including a national park and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. However, Eryri is being impacted by climate change and the loss of biodiversity – with those who live, work and play in the landscape, as well as those who manage it, facing changes.5 The UK’s Climate Change Committee calls this ‘the decisive decade’ to act, advising that transforming land use is one of four key areas Wales can take action on to reach net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050.6 Anticipating future change, and understanding the need for different management and land uses, can we still afford for Eryri to be perceived as a sublime and static landscape?

Patricia Stokowski writes that ‘social and cultural values of place ... become sustained in the language, culture, and history collectively experienced, imagined, and remembered across groups and communities of people.’7 This article exposes how past perceptions and expectations shaped Eryri and examines the actions that have perpetuated specific values of place since the early eighteenth century. It explores the historical fascination with representing a ‘truly British’ landscape, and the ‘top-down’ elitist view of the environment that fuelled the emergence of specialised industries and government legislation to rationalise land. The article establishes connections between these actions, the prevailing ideas of the time, and their influence on current understandings of the national park. In conclusion, the article proposes an active reframing of Eryri that would involve amplifying diverse voices, integrating various forms of knowledge, and incorporating new representation methods within the landscape decision-making process.

Evolving perceptions of Eryri

‘The fag End of Creation’

‘The Country looks like the fag End of Creation; the very Rubbish of Noah’s Flood; and will (if anything) serve to confirm an Epicurean in his Creed, That the World was made by Chance.’8 This quotation captures the impression of a traveller visiting Eryri in the early eighteenth century. The early 1700s saw the ‘Augustan’ phase of landscape design in the UK, where writers, architects and artists tried to recreate the energy and creativity achieved during the reign of the Roman emperor Augustus. Seeking out the mysteries of that specific antiquity became highly desirable as elites, and the landed gentry, embarked on month-long trips across Europe. They wished to be inspired, and energised, by what they saw and felt while at ancient Roman and Greek sites. They took with them artists and classical reading material, and brought back paintings, tales and ideas to impress their estates and peers.

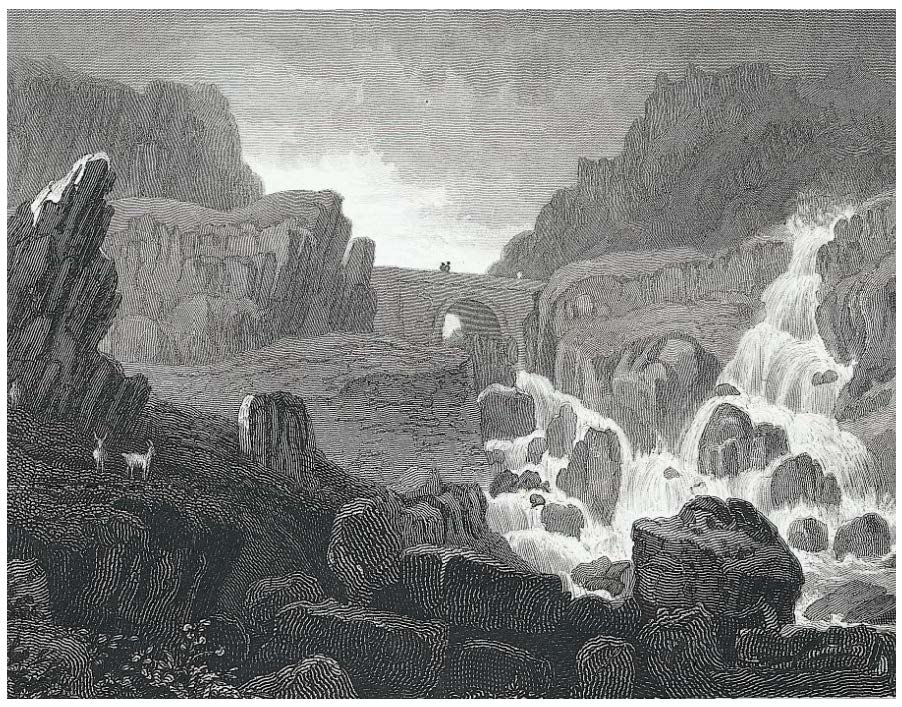

At a time when lavish gardens were being constructed in England, such as Studley Royal in Yorkshire and Stowe Gardens in Buckinghamshire, the landscapes of northwest Wales were seen as places of revulsion. These landscapes were framed as unimproved and unlikely to ever be transformed into productive agricultural land or beautiful scenery – and were thus described as distant, unpleasant places.9 To an Augustan observer, the mountains, valleys and bogs of northwest Wales were a sight unfit for a modern (geometric and rational) society (Figure 2). A proposal, not entirely in jest, suggested that places like Eryri were dumping grounds for the rubble of those more desirable private paradises typified by the already mentioned Studley Royal and Stowe Gardens.10

Fall of the Ogwen in Nant Frangon, Caernarvonshire by Henry G. Gastineau, engraver: H. Lacey, 1831, steel engraving, 9.3 x 14.5 cm (Source: The National Library of Wales. Accessed 27 July 2023. https://hdl.handle.net/10107/4675691)

During the eighteenth century, however, there was a noticeable change when it came to landscape design. Tom Turner explains that the Augustan phase ended in 1750, being supplanted by the ‘Brownian’, which saw landscape designers taking inspiration from ‘nature’s serpentine lines’.11 A third phase – ferme ornée – set out to create ornamental farms where their owners could appreciate the joint joys of nature and production.12 Turner also notes the changes in the design process, whereby in the Augustan phase a design was well planned and almost symmetrical, by the late 1700s a plan was subject to the owner’s particular beliefs about beauty and use. This evolution, from the symmetrical to the more natural, meant that the notion of a ‘true Britain’, with idyllic landscapes and pleasant rurality, came to the forefront.

‘Lads on tour’ … esque

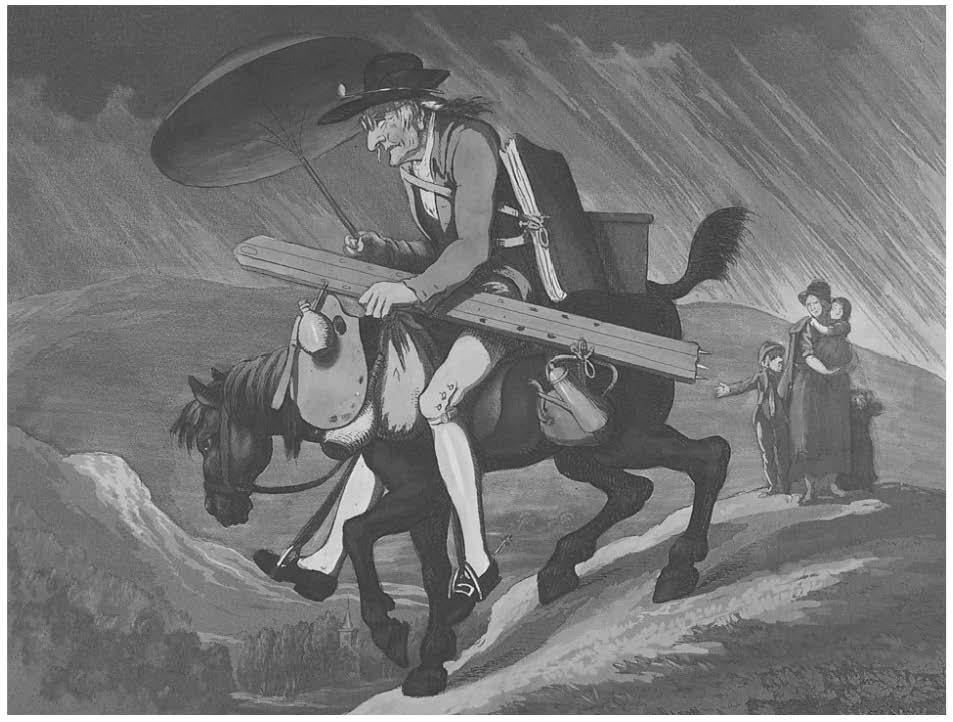

The tendency to describe Eryri as ‘the fag End of Creation’,13 ‘a fragment of a demolished world’14 or a ‘dumping ground’15 began to change by the late eighteenth century. Following many years of elites, and the landed gentry, exploring Europe on the Grand Tour, eyes began to search inwards. The call of the Scottish Highlands, Welsh mountains and peaks of England grew louder as industrialisation and modernisation were seen to be taking over (Figure 3). William Gilpin’s series of essays and published works about his Picturesque tours (published between 1782 and 1809) ‘awakened English tourists to the rugged delights of North Wales’.16

An Artist Travelling in Wales, after Thomas Rowlandson, etcher: Henri Merke, 1799, etching and aquatint with hand colouring, 33.5 x 39.4 cm (Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed 27 July 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/377646)

The first noted Picturesque tour of northwest Wales was undertaken in 1771 by Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn, who, just two years earlier, had finished touring and buying art in France, Switzerland and Italy.17 With him on his two-week tour was Paul Sandby, founder member of the Royal Academy and now remembered as the ‘Father of English Watercolour’. Sir Watkin was one of the wealthiest and most important men in eighteenth-century Wales, and his tour certainly set a trend. Their trip inspired many to take up the journey and, within only ten years of the first tour, the Welsh Tour became a standard undertaking for elites and the landed gentry.

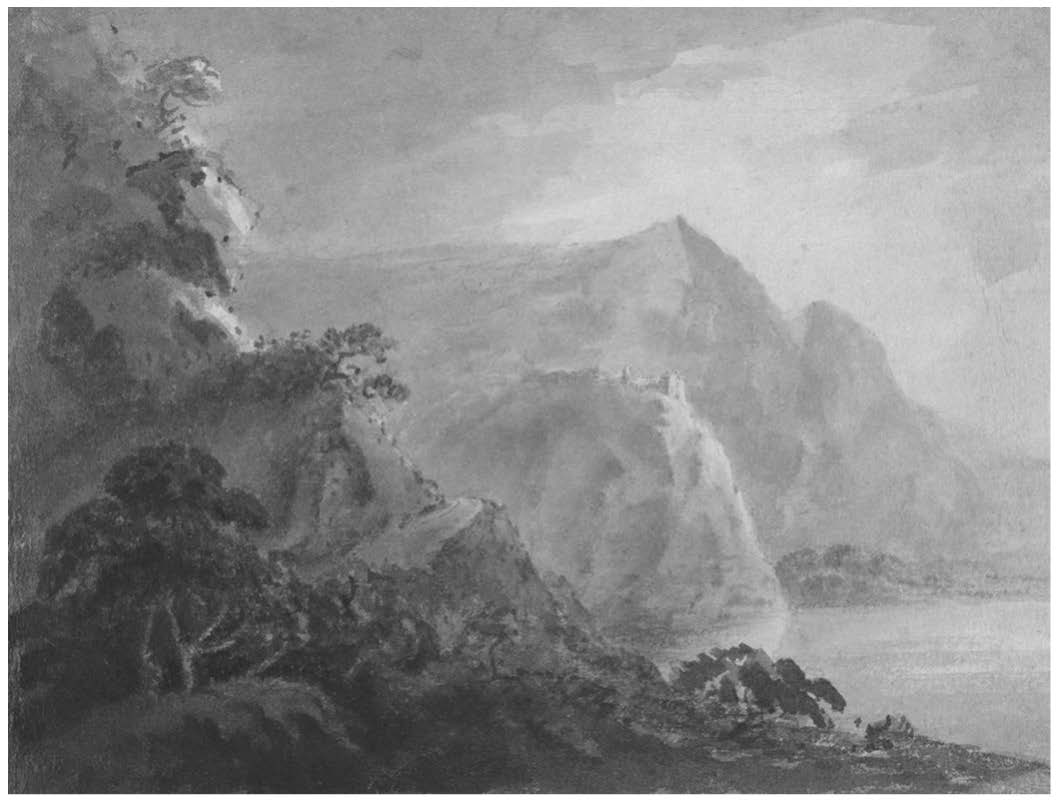

What were these tourists looking for? In the words of Gilpin, they searched for a ‘peculiar kind of beauty, which is agreeable in a picture’ (Figure 4).18 In the northwest of Wales, tourists searched for worlds ‘left forgot’, focusing on seeing the sublime, the beautiful and the picturesque – choosing to overlook the changing circumstances on the ground.19 An example of this can be found in Scotland, where William Gilpin’s observation differed from that of a tourist who followed his path 30 years later. When seeing Glen Croe, the pass west of Loch Lomond in Scotland, Gilpin’s description was of a pastoral idyll. ‘A lonely cottage, sheltered with a few trees, and adorned with its little orchard, and other appendages. We might call it the seat of empire,’ he wrote.20 The partiality of this description is countered by a closer observation made by a later tourist, who noted the tiny size of the cottage and the sub-standard conditions in which the cowherd and his family were living.

Gilpin’s oversight was due to his framing. He chose to base his understanding on the virtues of a simple rural life taken from Italian painters and classical authors. He went a step further and gave it an ‘English vernacular flavour’, which combined with a newly emerging eighteenth-century English (or British) national pride.21

While the Picturesque tours tried to discover ‘true Britain’ in northwest Wales, the landscape of Eryri was about to see a great change. In 1768, Richard Pennant consolidated the Penrhyn estate through inheritance and marriage, amassing a large amount of land. In doing so, he became one of the wealthiest and most influential men in North Wales. Pennant invested considerably in the area and transformed its working patterns, including by buying out the independent quarries and employing the independent quarrymen as wage labourers. The Crown lands were leased, and considerable infrastructure and transport links were built to make way for new heavy industry and agricultural production.22 Like much of Britain, Eryri was to be modernised as capitalist extractive practices were rolled out over the Penrhyn estate.

Landscape with Hill, Lake and Figures by William Gilpin, ca. 1772, pen and black ink, brush and grey wash on buff paper, 26.4 x 35.9 cm (Source: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Accessed 27 July 2023. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/417459)

Power, ownership and pompousness

Landscape remains a concept tied to the visual. This could be down to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) entry, which reads that landscape is ‘a picture representing natural inland scenery’.23 The OED also notes that the word landscape first entered the English language sometime in the 1600s and stems from the Dutch word landschap. Both Kenneth Olwig and Simon Schama, in their analysis of the word landscape, agree that it had been imported by the end of the sixteenth century from the Netherlands.24

As the word embedded itself in British culture, it evolved, taking on new meanings and overtones. This etymological change resulted in a strong relationship between landscape and the aesthetic. Denis Cosgrove explains that,

The growth of map making, surveying and estate drawings in the seventeenth century depended heavily on surveyors who were often artists.26 This coupling of roles and perspectives ushered in a top-down and scientific way of framing land which ‘revolutionised perception … [and] created a new way of conceptualising and thinking about landscape that was based on the point of view of an individual rather than on the experience of a local community of people sharing the land’.27 The individual – the painter, poet, writer, surveyor, map maker or land owner – became the one who chose the ‘framing’ of the landscape on paper, the one in control.28 The concept of ‘landscape’ in the UK, and the West, revolves around a ‘scenic, elitist “viewpoint”’.29at both the local and national level, and in their political rivalries too, landscape emerged from Landschaft with a totally transformed meaning, and the transformation was at once social and spatial. Socially, landscape was divested of attachment to a local community and its customary law and handed to the ‘distanciated gaze’ of a property owner whose rights over the land were established and regulated by statute. Spatially, landscape was constructed as a bounded and measured area, an absolute space, represented through the scientific techniques of measured distance, geometrical survey, and linear perspective. In this respect, landscape should be understood as a direct expression of modernization.25

The developing industry of representing landscapes cannot be separated from the wider capitalist and colonial system of the time. Maps and surveys strengthened landowners’ claims and their control over physical land – allowing, for example, the clearing and developing of Crown and common lands.30 Upholding these power dynamics and helping to legitimise these actions were ties to the military.31 Often, estates had access to high-ranking officials, while some surveyors and artists were, or had been, part of the military. Archive material in Bangor University’s Penrhyn Estate Archives shows that a Colonel Claudius Shaw was responsible for an 1840 map of the lower part of Llandygai parish for the Penrhyn estate.32 Before joining Sir Watkin Williams-Wynn on his tour of Eryri, Paul Sandby was a military draughtsman and map maker for the Board of Ordnance.33

The representation of landscape through topographical maps helped foster the newly emerging eighteenth-century English (or British) national pride. Denis Cosgrove writes about the ‘centrality of landscape in framing national identity’ and how topographical maps are used as representations of a nation.34 Owning and being able to read the nation’s landscape using a map, along with knowing how to behave in accordance with the map’s guidance, can be held as a sign of citizenship.35 This top-down guide on conducting oneself in the landscape adds to the layers of control instilled within the ways in which maps, and other historical modes of representation, perpetuated certain power dynamics. Maps, along with other modes of representing landscape, enabled ideas and attitudes towards order, power and meaning to be expressed and shared widely.36 Even the simple acts of gardening and drawing instilled specific values towards nature within society.37 Through the tours, surveying and painting of Eryri, it became a site ‘of specific ideological attitudes and ambivalences’.38 These attitudes, together with particular meanings fixed and circulated on maps and other modes of representation, continue to inform the ways our society perceives landscapes such as Eryri.39

The main frames through which landscape was understood were influenced by the ways of representing those same landscapes, and vice versa. Additionally, the tools and methods – such as painting, drawing and mapping – became intrinsic to the frames which substantiated, and expanded, the emerging capitalist and colonial society.40 With the changes brought about by the agricultural and industrial revolutions, land became increasingly seen as something that could be spatially divided into compartments – a thing that could be measured and labelled ‘wild nature’, ‘country’ or ‘urban’.41 The ideologies and values that framed the landscape informed the actions and, in turn, shaped both the physical space and ‘life experienced and performed there’.42

Influencing legacies

In 1942, the minister of works and buildings, in consultation with the minister of agriculture, appointed the Scott Committee to identify the problems within rural society and provide solutions. The Scott Committee report concluded that the key solution was ‘to put agriculture back on its feet through subsidies while keeping the town at bay through establishing a comprehensive, centralised system of town and country planning’.43 The report also recommended the creation of national parks and nature reserves, which later led to the establishment of Parc Cenedlaethol Eryri (Eryri National Park) in 1951.

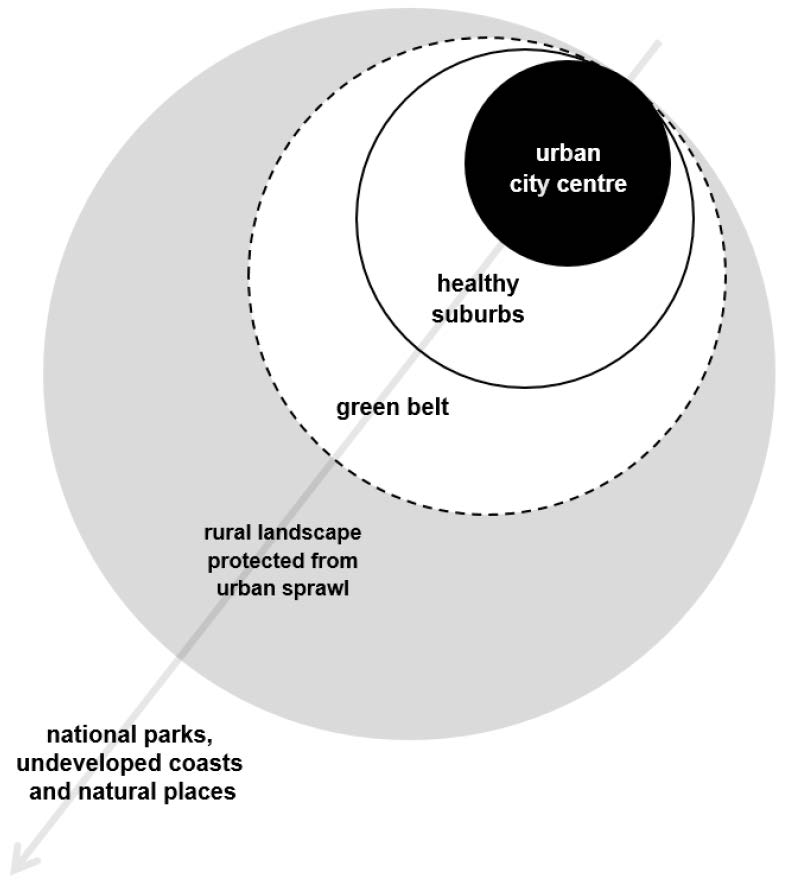

The Scott report’s recommendation to keep ‘the town at bay’ stems from negative experiences, and memories of landscape change, during the Industrial Revolution and could be attributed to the landscape designer Uvedale Price’s thinking in the late eighteenth century.44 Uvedale Price, along with scholar Richard Payne Knight and landscape designer Humphry Repton, were the proponents of the ‘transition style’. Their collective works and theories of the Picturesque became the first port of call for nineteenth-century landscape theorists considering landscape aesthetics.45 The transition style, a term coined by Tom Turner, describes the theory championed by Price, Knight and Repton.46 The style, much like in a painting, focuses on organising a landscape garden to facilitate a transition from the ‘Beautiful’ foreground, through a ‘Picturesque’ middle ground to a ‘Sublime’ background.47 The theory sought to add to Edmund Burke’s 1757 treatise on aesthetics, where he defines Beauty as that which stimulates love and the Sublime as that which causes astonishment.48 The Picturesque, in the middle ground, was an area that has attributes of both the Beautiful and the Sublime. Beyond the landscape garden, Price conceived a way that this style could be implemented to negotiate the relationship between urban and rural areas, as shown in Figure 5.

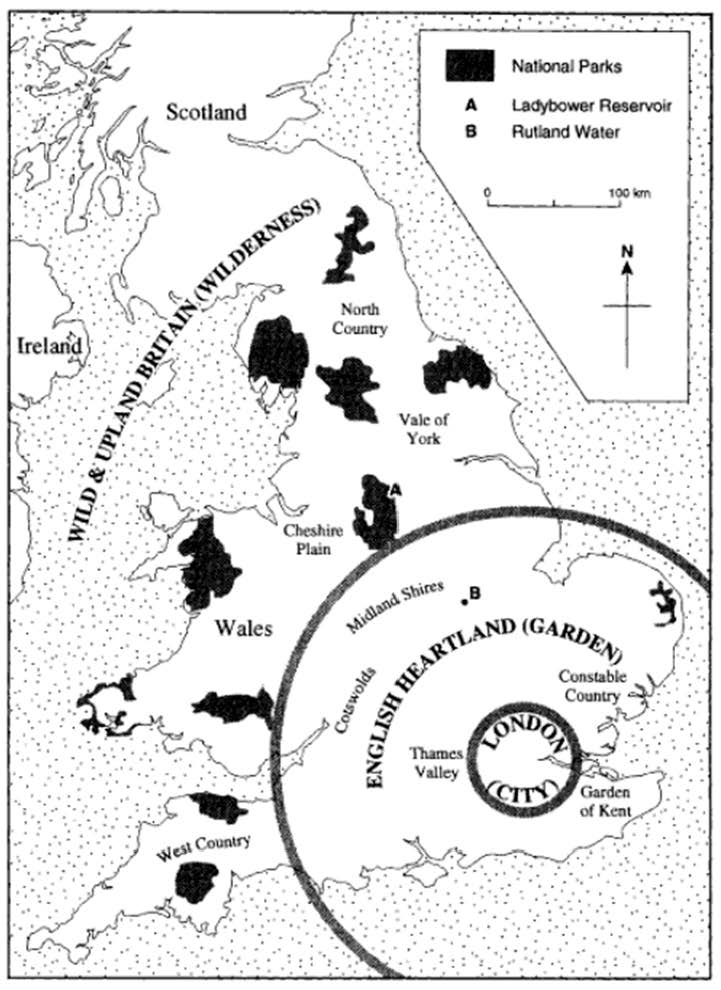

In the post-war years, the preservation of the countryside, and threats to rural Britain, were the main impetus for the Scott report and the three Acts that followed: the Agriculture Act (1947);49 the Town and Country Planning Act (1947);50 and the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act (1949).51 These three Acts laid the ground for Britain’s current landscape decision-making system.52 Notions of Price’s preservation thinking can be observed in the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act of 1949, which states that a national park compromises ‘those extensive tracts of country’ chosen ‘by reason of (a) their natural beauty and (b) the opportunities they afford for open-air recreation, having regard both to their character and their position in relation to centres of population.’53 As shown in Figure 6, the relationship of Eryri to ‘centres of population’54 situates such a landscape as a background to urban living, instilling it with the expectation of being a ‘distant place’, a ‘destination’ or highly associated with nature and health – presenting those qualities as integral to its understanding.55

Current understandings and expectations of landscapes such as Eryri are intimately linked to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century ideas and theories. Jala Makhzoumi writes that those theories ‘played a pivotal role … in shaping the contemporary meaning of the word “landscape” … They influenced public expectations of the landscape profession towards the scenic and pictorial’.56 John Walton substantiates this by writing that ‘the second half of the eighteenth century … transformed perceptions … making maritime and upland landscapes attractive, evocative and exciting under the rubrics of the Picturesque’.57

The development of the three Acts in the late 1940s provided a system to control and order the landscape, allowing for what Harriet Atkinson calls the ‘New Picturesque’ movement. Together with the New Towns Act of 1948, new uses or developments in the landscape were subject to control by local planning authorities, or county councils, to ensure that they were in line with new plans.58 London was the linchpin for the New Picturesque movement, with the government and public authorities used as instruments to spread the ideas across the UK.59 However, the assumptions and dreams outlined in the Acts – of a ‘traditional’, ‘picturesque British landscape’ – failed to anticipate the change in post-war farming and the consequences of that change on rural communities.

‘Productionist incentives and pressures led farmers to expand both at the extensive and intensive margins. Farmers brought new land into use, or upgraded the use of existing agricultural land, by draining marshland, ploughing up moorland, grubbing up woods and removing hedgerows’.60 These actions were a result of the Acts being written at a time when ‘agricultural exceptionalism’ was believed to be the answer. The main proponents of the Acts, as well as planners of the 1940s, believed that the largest threat to the countryside was urban expansion, leading to the assumption that rural landowners could be exempted from nearly all planning controls as long as they kept their land in agricultural use.61

The Picturesque movement of the eighteenth century, as well as its resurgence as the New Picturesque in the early twentieth century, promoted a limited frame through which to understand the British landscape. The culture of the eighteenth-century elite ‘created environments of the mind and the soil [that] fantasized the harmony of human production and natural sustainability.’62 This fantasy of the elite, positioned at a privileged vantage point,63 fuelled Gilpin’s guidance for finding a ‘peculiar kind of beauty’ and wrote the ruling on land having a single, exclusive function as assumed in the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act of 1949. However, the fantasy had real-world impacts, with people’s livelihoods being greatly affected. The contribution of the three Acts alone to the biodiversity crisis has been significant and the transformation of the British countryside that they ushered in has been extensive.64

Towards an active reframing of Eryri

The frames through which we understand and then negotiate landscapes are, in and of themselves, impactful.

In the study of environmental conflicts, framing ‘refers to the process of constructing and representing our interpretations of the world around us’ and ‘involves a representational process in which we present or express how we make sense of things’.65 These framings can change and evolve with time, which we can see in the changing perceptions and representations of Eryri since the 1700s. Figure 7 presents the key moments that these changes occurred through the lens of landscape studies. There is a dramatic shift from the 1700s, when Eryri’s landscape features were described as a revulsion, to the mid-twentieth century, when Eryri was enshrined as a national park – one whose landscape features should be protected.

However cherished and protected, landscapes such as Eryri are undergoing change. Natural Resources Wales (NRW) warns that climate change is projected to increase the frequency and intensity of heatwaves, droughts, and river and coastal floods. These are all expected to reduce ecosystem resilience further.66 The Climate Change Committee advises that transforming land is one of four key areas in which Wales can take action to reach net zero.67 Adaptation measures and the sustainable management of landscapes are increasingly making their way into the plans of land-owning organisations and into national and local policy.68 However, the University of Reading’s Review of Key Trends and Issues in UK Rural Land Use concluded that ‘land use decision-making in the UK remains extremely fragmented and still insufficiently democratised’.69 The review continues, writing that ‘tensions between stakeholders, and between stakeholders and policymakers … have persisted against themes of development, recreation and conservation’.70 These tensions between insiders and outsiders have been at the centre of developments within procedural planning theory over the last few decades.71

The Welsh government itself calls for ‘every citizen, community, group and business in Wales to embed the climate emergency in the way they think, work, play and travel’.72 Engaging and involving all aspects of society is integral to tackling climate change and biodiversity loss.73 Public opinion is recognised as a vital part of successful policy responses to mitigate climate change.74 However, a project as recently as 2022, led by the organisation Land Use Consultants and commissioned by NRW, lacked the involvement of local collaborators and members of the public.75 The aim of the project was to develop a map of visually tranquil places in Wales, a resource which is ‘to be an evidence base to inform policy intent, practice and provision for well-being benefits’.76 The report’s key output was a series of indicators generated in two stakeholder workshops. The workshops only involved landowners, staff from local councils and land management organisations, instilling the indicators with a limited understanding and perception of the landscape.

National parks are ‘inevitably a reflection of the beliefs, values and desires of those in power at the time of their creation’.77 This article presents the beliefs, values and desires that led to the enshrining of Eryri as a national park and shows how they are the foundations of its perception and long-term management. How do we challenge these narrow understandings of landscapes such as Eryri? How can we instil different expectations and disrupt the systems that perpetuate unequal power relations and embedded politics? Questions such as these are of central importance in stimulating an ‘ethical enterprise’,78 or enquiry, concerning a subject like Eryri. This article exposes ‘the dominant ideology … as manufactured instead of natural’,79 thus helping to define the underlying problem with current prevailing framings of Eryri. ‘Defining a problem is a political act’ and maybe a political act is what is needed.80 An active reframing of Eryri would challenge current power dynamics and representations embedded in the landscape decision-making system of northwest Wales.

There is already a body of work on which this active reframing can draw. Projects following the same trajectory of thought have focused on other national parks in Europe. In the Drents-Friese Wold National Park, in the Netherlands, Arjen Buijs conducted a series of focus groups with local residents to stimulate exchanges to understand their framings of the park and of ongoing issues.81 Buijs’s tabulation of findings gathers the three dominant ways represented in the focus groups (see Table 1).82 Buijs reveals how these representations are used by the National Forest Service and the Woodland Giant (a local pressure group) to communicate with the park’s management. By combining framing theory with social representations theory, this ‘enables one to disentangle the volatile discourses in the framing of environmental disputes from the more stable cultural values and opinions on which the cultural resonance of a frame is based’.83

In the Lake District and the Trossachs, in the UK, Nick Hanley and his fellow researchers used a questionnaire to survey local residents and visitors to ‘investigate the effects of providing information on past landscapes on preferences towards future landscape change’.84 In the Lake District, they presented respondents with historical travellers’ accounts, whereas in the Trossachs they shared maps from different periods showing considerable woodland change. In both case-study areas, respondents were more likely to prefer change when ‘learning that landscape evolves in physical terms but also in terms of how it is perceived reduces peoples’ [sic] desire to keep the current landscape as fixed and un-changing.’85

These studies show that an active reframing of Eryri is possible when research and landscape decision-making processes collaborate with the public and incorporate, and help to expose, the underlying ideologies within a given landscape.

The dominant social representations of nature held by the local residents of Drents-Friese Wold National Park (Source: Buijs, 2009)

| Social representations of nature | Normative elements | Cognitive elements | Expressive elements | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value of nature | Value orientation Management focus |

Boundary of nature | Dominant beliefs about nature | Emotions evoked by nature | |

| Wilderness | Ecocentric | Natural processes No management |

Narrow (only purely autonomous life forms) | Nature as fragile Scientifically intelligible |

Beauty of nature: Uncultivated Awe Fascination |

| Inclusive | Biocentric | Limited management Management focused on nature |

Wide (every life form) | Nature as fragile Nature as dynamic Nature as unpredictable |

Beauty of nature: Uncultivated + well-groomed Fascination Vitality |

| Aesthetic | Weak anthropocentric | Landscape management | Moderately wide (non-cultural) | Nature as fragile Balance of nature |

Beauty of nature: Well-groomed Sensory experiences Diversity of landscape Attachment |

Conclusion

In the early eighteenth century, according to Ann Bermingham,

The historical modes of representation (paintings, drawings, maps and plans), the then newly established, specialised industries (surveyors and map makers) and twentieth-century government legislation, have all helped to strengthen and perpetuate a limited framing of landscape. The top-down, elitist rationalisation of the environment and the legacies of longing to find a ‘truly British’ landscape continue to not only influence people’s perceptions and expectations of Eryri but also to impact its nonhuman entities and physical elements. This article argues that the ‘seemingly organic operations’ embedded into our society in the early eighteenth century continue to influence our perceptions and expectations of landscape today.87 Recognising that certain underlying ideologies exist, and exploring how they underpin the dominant representations and values of Eryri, is a first step towards ‘reframing’ the landscape. With the environment being ‘a central component of the functioning of … British democracy’,88 it is important for more research to be conducted on how the public’s perceptions and expectations interrelate and inform landscape change in Britain.a reordering of the representational field into a variety of specialized areas of knowledge and experience … internalized … intricate, multileveled, seemingly organic operations … such a reordering of representation had important implications … for it ultimately reconfirmed the need for order without seeming to do so.86

An active reframing of Eryri requires an approach which is collaborative, creative and caring. It needs to be grounded in multiple voices, involve diverse forms of knowledge and incorporate different ways of understanding within the landscape decision-making process.89 It should ‘not only direct reactions to management options, but also [to] the representations that underpin public attitudes towards the management of the natural environment’.90 It would incorporate the questioning of current, and possible future, perceptions and representations of the landscape. The process of reframing Eryri should be reiterative, responding to the ongoing threats of climate change and biodiversity loss.

The next step to actively reframe Eryri is to develop an approach, alongside local people and those already involved in the landscape decision-making process. The approach would contribute towards answering the following questions:

-

1)

What are the dominant frames held by the public and landscape managers about the landscape of Eryri?

-

2)

How do the dominant framings of the landscape influence decision making?

-

3)

What alternative frames are available to understand current and future change?

-

4)

What are the creative practices, and visual representations, that can help reframe Eryri in the public mind?

This is the decisive decade; the methods and practices we use to represent and frame landscapes are, in and of themselves, impactful. This is an opportune moment to tackle the embedded politics, power relations and responsibilities connected to landscapes such as Eryri. Through our choices, we can either perpetuate ideologies and past ambivalences or make a break to tackle climate change and biodiversity loss. We can choose the frames through which we see our landscapes and can aim to ‘not see them as simply scenic texts’ but as places that require substantive understanding.91

Notes

- Makhzoumi and Pungetti, Ecological Landscape Design and Planning. ⮭

- Hanley et al., ‘The impacts of knowledge of the past’. ⮭

- See, for example, Williams, ‘The geology of Snowdon’; Bennett, ‘The landscape beneath our feet’. Also, Sheddon, ‘Late-glacial deposits’; Good, Bryant and Carlill, ‘Distribution, longevity and survival of upland hawthorn’. ⮭

- Eryri National Park Authority, ‘Landscapes & wildlife’. ⮭

- Eryri National Park Authority, ‘Climate change’. ⮭

- Climate Change Committee, Advice Report. ⮭

- Stokowski, ‘Languages of place and discourses of power’, 373. ⮭

- Anon., ‘Tour in the summer’, 109. ⮭

- Andrews, The Search for the Picturesque. ⮭

- Andrews, The Search for the Picturesque. ⮭

- Turner, English Garden Design, 83. ⮭

- Turner, English Garden Design. ⮭

- Anon., ‘A trip to North Wales’. ⮭

- Lyttelton, Account. ⮭

- Andrews, The Search for the Picturesque. ⮭

- Turner, English Garden Design. ⮭

- Amgueddfa Cymru, ‘The Williams-Wynn collection’, https://museum.wales/collections/art/williams-wynn (accessed 8 February 2023). ⮭

- Gilpin, An Essay upon Prints. ⮭

- Andrews, The Search for the Picturesque. ⮭

- Gilpin, High-Lands II, 11–12. ⮭

- Andrews, The Search for the Picturesque. ⮭

- Jones, The North Wales Quarrymen. ⮭

- OED Online, ‘landscape, n.’. ⮭

- Olwig, The Meanings of Landscape. ⮭

- Cosgrove, ‘Landscape and Landschaft’. ⮭

- Cosgrove, ‘Landscape and Landschaft’. ⮭

- Olwig et al., ‘Introduction to a special issue’. ⮭

- Daniels, ‘Marxism, culture and the duplicity of landscape’. See also Cosgrove, ‘Prospect, perspective’. ⮭

- Makhzoumi, ‘Landscape in the Middle East’. ⮭

- Jones, ‘The North Wales Quarrymen’. ⮭

- Bermingham, ‘System, order and abstraction’. ⮭

- Bangor University Archives and Special Collections [Map of the Lower Part of Llandegai Parish]. ⮭

- Bishop, The Mountains of Snowdonia in Art, 20. ⮭

- Cosgrove, ‘Landscape and Landschaft’. ⮭

- Cosgrove, ‘Landscape and Landschaft’. ⮭

- Bermingham, ‘System, order and abstraction’. ⮭

- Bermingham, ‘System, order and abstraction’. ⮭

- Bermingham, ‘System, order and abstraction’. ⮭

- Dodge, Kitchin and Perkins, The Map Reader. ⮭

- Mitchell, Landscape and Power. ⮭

- Cosgrove, ‘Modernity’. ⮭

- Cosgrove, Geography and Vision. ⮭

- Burchardt, Doak and Parker, Review of Key Trends and Issues in UK Rural Land Use. ⮭

- Turner, English Garden Design. ⮭

- It is important to note that Uvedale Price and Richard Payne Knight were landowners and incredibly wealthy. ⮭

- Tom Turner now calls the transition style the ‘landscape style’. ⮭

- Townsend, ‘The Picturesque’. ⮭

- Burke, A Philosophical Enquiry. ⮭

- United Kingdom, Public General Acts, The Agriculture Act 1947, adopted 6 August 1947. ⮭

- United Kingdom, Public General Acts, Town and Country Planning Act 1947, adopted 6 August 1947. ⮭

- United Kingdom, Public General Acts, National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949, adopted 16 December 1949. ⮭

- Burchardt, Doak and Parker, Review of Key Trends and Issues in UK Rural Land Use. ⮭

- United Kingdom, Public General Acts, National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. ⮭

- United Kingdom, Public General Acts, National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. ⮭

- Cosgrove, Roscoe and Rycroft, ‘Landscape and identity’. ⮭

- Makhzoumi, ‘Landscape in the Middle East’. ⮭

- Wood and Walton, The Making of a Cultural Landscape, 32. ⮭

- MacEwen and MacEwen, National Parks. ⮭

- Atkinson, ‘A “New Picturesque”?’. ⮭

- Burchardt, Doak and Parker, Review of Key Trends and Issues in UK Rural Land Use. ⮭

- Burchardt, Doak and Parker, Review of Key Trends and Issues in UK Rural Land Use. ⮭

- Porter, ‘In England’s green and pleasant land’. ⮭

- Townsend, ‘The Picturesque’. ⮭

- Burchardt, Doak and Parker, Review of Key Trends and Issues in UK Rural Land Use, 21. ⮭

- Gray, ‘Framing of environmental disputes’. ⮭

- Natural Resources Wales, Executive Summary of The State of Natural Resources Report 2020. ⮭

- Climate Change Committee, Advice Report. ⮭

- See, for example, Welsh government, Prosperity for All; National Trust, ‘Upper Conwy catchment project’. ⮭

- Burchardt, Doak and Parker, Review of Key Trends and Issues in UK Rural Land Use. ⮭

- Burchardt, Doak and Parker, Review of Key Trends and Issues in UK Rural Land Use. ⮭

- Bourassa, The Aesthetics of Landscape. ⮭

- Welsh Government, Climate Change. ⮭

- Natural Resources Wales, Executive Summary of The State of Natural Resources Report 2020. ⮭

- Pietsch and McAlister, ‘“A diabolical challenge”’. ⮭

- Green, Manson and Chamberlain, Tranquillity and Place. ⮭

- Green, Manson and Chamberlain, Tranquillity and Place. ⮭

- Suckall, Fraser and Quinn, ‘How class shapes perceptions of nature’. ⮭

- Robb, ‘A framework for feminist ethics’. ⮭

- Robb, ‘A framework for feminist ethics’. ⮭

- Robb, ‘A framework for feminist ethics’. ⮭

- See Moscovici, La psychanalyse. ⮭

- Buijs, Public Natures. ⮭

- Buijs, Public Natures. ⮭

- Hanley et al., ‘The impacts of knowledge of the past’. ⮭

- Hanley et al., ‘The impacts of knowledge of the past’. ⮭

- Bermingham, ‘System, order and abstraction’. ⮭

- Bermingham, ‘System, order and abstraction’. ⮭

- Kelly, ‘The politics of the British environment since 1945’. ⮭

- Rahman et al., ‘Locally led adaptation’. ⮭

- Buijs et al., ‘Looking beyond superficial knowledge gaps’. ⮭

- Olwig, The Meanings of Landscape. ⮭

Declarations and conflicts of interest

Research ethics statement

Not applicable to this article.

Consent for publication statement

Not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of interest statement

The author declares no conflicts of interest with this work. All efforts to sufficiently anonymise the author during peer review of this article have been made. The author declares no further conflicts with this article.

References

Andrews, Malcolm. (1989). The Search for the Picturesque: Landscape aesthetics and tourism in Britain, 1760–1800. Stanford, CA: Scholar Press.

Anon. (1989). ‘Tour in the summer 1776. Through Wales’, National Library of Wales MS.2862.A., f. 37. Quoted in The Search for the Picturesque: Landscape aesthetics and tourism in Britain, 1760–1800, by Malcolm Andrews, 109. Stanford, CA: Scholar Press.

Anon. (1738). ‘A trip to North Wales’. A Collection of Welsh Travels, and Memoirs of Wales, Torbuck, John (ed.), London: : 4–5.

Atkinson, Harriet. (2008). ‘A “New Picturesque”? The aesthetics of British reconstruction after World War Two’. Edinburgh Architecture Research 31 : 24–35.

Bangor University Archives and Special Collections. (2015). [Map of the Lower Part of Llandegai Parish, Surveyed by John Jones, Linen backed; coloured; scale 1 inch 4 chains]. (1840). Penrhyn Castle Additional Manuscripts (1. Maps and Plans, PENRA/2214), Bangor University, Bangor, United Kingdom. Peter Bishop, The Mountains of Snowdonia in Art. Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, p. 20.

Bennett, Matthew R. (2022). ‘The landscape beneath our feet’. Our Dynamic Earth: A primer, by Matthew Bennett, 85–100. Cham: Springer.

Bermingham, Ann. (2002). ‘System, order and abstraction: The politics of English landscape drawing around 1795’. Landscape and Power. 2nd edn. Mitchell, William J. T (ed.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 77–101.

Bishop, Peter. (2015). The Mountains of Snowdonia in Art. Llanrwst: Gwasg Carreg Gwalch.

Bourassa, Steven C. (1991). The Aesthetics of Landscape. London: Belhaven Press.

Buijs, Arjen E. (2009). Public Natures: Social representations of nature and local practices. Wageningen: Wageningen University and Research.

Buijs, Arjen E; Fischer, Anke; Rink, Dieter; Young, Juliette C. (2008). ‘Looking beyond superficial knowledge gaps: Understanding public representations of biodiversity’. International Journal of Biodiversity Science & Management 4 (2) : 65–80, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3843/biodiv.4.2:1

Burchardt, Jeremy; Doak, Joe; Parker, Gavin. (2020). Review of Key Trends and Issues in UK Rural Land Use: Living Landscapes project, final report to the Royal Society. Reading: University of Reading.

Burke, Edmund. (1779). A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful. The sixth edition. With an introductory discourse, concerning taste... to which is added, a vindication of natural society, etc. London: Gale ECCO.

Climate Change Committee. (2020). Advice Report: The path to a net zero Wales. London: The Climate Change Committee.

Cosgrove, Denis. (2008). Geography and Vision: Seeing, imagining and representing the world. London: I.B. Tauris.

Cosgrove, Denis. (2004). ‘Landscape and Landschaft’. Lecture delivered at the ‘Spatial Turn in History’ Symposium, German Historical Institute, Washington, DC, USA. February 19 2004

Cosgrove, Denis. (2006). ‘Modernity, community and the landscape idea’. Journal of Material Culture 11 (1–2) : 49–66, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1359183506062992

Cosgrove, Denis. (1985). ‘Prospect, perspective and the evolution of the landscape idea’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 10 (1) : 45–62, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/622249

Cosgrove, Denis; Roscoe, Barbara; Rycroft, Simon. (1996). ‘Landscape and identity at Ladybower Reservoir and Rutland Water’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 21 (3) : 534. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/622595

Daniels, Stephen. (1989). ‘Marxism, culture and the duplicity of landscape’. New Models in Geography, the Political–Economy Perspective, Vol. 2. Peet, Richard, Thrift, Nigel Nigel (eds.), London: Unwin and Hyman, pp. 196–220.

Dodge, Martin; Kitchin, Rob; Perkins, Chris. (2011). The Map Reader: Theories of mapping practice and cartographic representation. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell.

Eryri National Park Authority. (). ‘Climate change’. https://snowdonia.gov.wales/protect/challenges/climate-change/. Accessed 21 June 2023

Eryri National Park Authority. (). ‘Landscapes & wildlife’. https://snowdonia.gov.wales/discover/landscapes-and-wildlife/. Accessed 19 July 2023

Gilpin, William. (2014). An Essay upon Prints: Containing remarks upon the principles of picturesque beauty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gilpin, William. (1989). High-Lands II, pp. 11–12. Quoted in The Search for the Picturesque: Landscape aesthetics and tourism in Britain, 1760–1800. Andrews, Malcolm (ed.), Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, p. 6.

Good, J. E. G; Bryant, R; Carlill, P. (1990). ‘Distribution, longevity and survival of upland hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) scrub in North Wales in relation to sheep grazing’. Journal of Applied Ecology 27 (1) : 272–83, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2403584

Gray, Barbara. (2003). ‘Framing of environmental disputes’. Making Sense of Intractable Environmental Conflicts: Concepts and cases. Lewicki, Roy, Gray, Barbara; Barbara and Elliott, Michael Michael (eds.), Washington, DC: Island Press, pp. 11–34.

Green, Chris; Manson, Diana; Chamberlain, Kimberley. (2022). Tranquillity and Place, NRW Report No: 569. Cardiff: Natural Resources Wales.

Hanley, Nick; Ready, Richard; Colombo, Sergio; Watson, Fiona; Stewart, Mairi; Bergmann, E. Ariel. (2009). ‘The impacts of knowledge of the past on preferences for future landscape change’. Journal of Environmental Management 90 (3) : 1404–12, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.08.008 [PubMed]

Jones, R. Merfyn. (1981). The North Wales Quarrymen, 1874–1922. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

Kelly, Matthew. (2023). ‘The politics of the British environment since 1945’. The Political Quarterly 94 (2) : 208–15, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-923x.13275

Lyttelton, George. (1775). Account, quoted in A Gentleman’s Tour through Monmouthshire and Wales, in the months of June and July, 1774, by Henry Wyndham, Wyndham, Henry (ed.), London:

MacEwen, Ann; MacEwen, Malcolm. (1982). National Parks: Conservation or cosmetics?. London: Allen & Unwin.

Makhzoumi, Jala. (2002). ‘Landscape in the Middle East: An inquiry’. Landscape Research 27 (3) : 213–28, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01426390220149494

Makhzoumi, Jala; Pungetti, Gloria. (2003). Ecological Landscape Design and Planning. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis.

Mitchell, William J. T. (2002). Landscape and Power. 2nd edn. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Moscovici, Serge. (1961). La psychanalyse, son image et son public. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

National Trust. (). ‘Upper Conwy catchment project’. https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/visit/wales/upper-conwy-catchment-project. Accessed 21 July 2023

Natural Resources Wales. (2020). Executive Summary of the State of Natural Resources Report 2020, by Natural Resources Wales. Cardiff: Natural Resources Wales.

Olwig, Kenneth. (2019). The Meanings of Landscape: Essays on place, space, environment and justice. London: Routledge.

Olwig, Kenneth R; Dalglish, Chris; Fairclough, Graham; Herring, Peter. (2016). ‘Introduction to a special issue: The future of landscape characterisation, and the future character of landscape – between space, time, history, place and nature’. Landscape Research 41 (2) : 169–74, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2015.1135321

Oxford English Dictionary Online. (2022). ‘landscape, noun,’. Oxford University Press. May 26 2022 https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/105515?rskey=EXPb0n&result=1&isAdvanced=false#eid. Accessed 8 September 2023

Pietsch, Juliet; McAlister, Ian. (2010). ‘“A diabolical challenge”: Public opinion and climate change policy in Australia’. Environmental Politics 19 (2) : 217–36, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09644010903574509

Porter, Roy. (2000). ‘In England’s green and pleasant land’. Culture, Landscape, and the Environment: The Linacre lectures 1997. Flint, Kate, Morphy, Howard Howard (eds.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 15–43.

Rahman, M. Feisal; Falzon, Danielle; Robinson, Stacy-ann; Kuhl, Laura; Westoby, Ross; Omukuti, Jessica; Schipper, E. Lisa F; McNamara, Karen E; Resurrección, Bernadette P; Mfitumukiza, David; Nadiruzzaman, Md. (2023). ‘Locally led adaptation: Promise, pitfalls, and possibilities’. Ambio 52 (10) : 1543–57, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13280-023-01884-7 [PubMed]

Robb, Carol S. (1981). ‘A framework for feminist ethics’. Journal of Religious Ethics 9 (1) : 48–68.

Seddon, B. (1962). ‘Late-glacial deposits at Llyn Dwythwch and Nant Ffrancon, Caernarvonshire’. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological Sciences 244 : 459–81, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rstb.1962.0002

Stokowski, Patricia. (2002). ‘Languages of place and discourses of power: Constructing new senses of place’. Journal of Leisure Research 34 (4) : 368–82, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2002.11949977

Suckall, Natalie; Fraser, Evan; Quinn, Claire. (2009). ‘How class shapes perceptions of nature: Implications for managing visitor perceptions in upland UK’. Drivers of Environmental Change in Uplands. Bonn, Aletta, Allott, Tim; Tim and Hubacek, Klaus; Klaus, Stewart, Jon Jon (eds.), London: Routledge, pp. 421–31.

Townsend, Dabeny. (1997). ‘The picturesque’. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 55 (4) : 365–76, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1540_6245.jaac55.4.0365

Turner, Tom. (1986). English Garden Design: History and styles since 1650. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors Club.

United Kingdom. (). Public General Acts, The Agriculture Act 1947, adopted 6 August 1947. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/10-11/48. Accessed 21 August 2023

United Kingdom. (). Public General Acts, National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949, adopted 16 December 1949. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/12-13-14/97. Accessed 21 August 2023

United Kingdom. (). Public General Acts, Town and Country Planning Act 1947, adopted 6 August 1947. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1947/51. Accessed 21 August 2023

Welsh Government. (2022). Climate Change – A strategy for public engagement & action, Consultation Document. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

Welsh Government. (2019). Prosperity for All: A climate conscious Wales: A climate change adaptation plan for Wales. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

Williams, Howel. (1927). ‘The geology of Snowdon, North Wales’. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London 83 (1–5) : 346–96, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1144/GSL.JGS.1927.083.01-05.14

Wood, Jason; Walton, John K. (2013). The Making of a Cultural Landscape: The English Lake District as tourist destination, 1750–2010. London: Routledge.