Commenting on an exhibition of contemporary Mexican architecture in Rome in 1957, the polemic and highly influential Italian architectural critic and historian, Bruno Zevi, ridiculed Mexican modernism for combining Pre-Columbian motifs with modern architecture. He referred to it as ‘Mexican Grotesque.’1 Inherent in Zevi’s comments were an attitude towards modern architecture that defined it in primarily material terms; its principle role being one of “spatial and programmatic function.” Despite the weight of this Modernist tendency in the architectural circles of Post-Revolutionary Mexico, we suggest in this paper that Mexican modernism cannot be reduced to such “material” definitions. In the highly charged political context of Mexico in the first half of the twentieth century, modern architecture was perhaps above all else, a tool for propaganda.

In this political atmosphere it was undesirable, indeed it was seen as impossible, to separate art, architecture and politics in a way that would be a direct reflection of Modern architecture’s European manifestations. Form was to follow function, but that function was to be communicative as well as spatial and programmatic. One consequence of this “political communicative function” in Mexico was the combination of the “mural tradition” with contemporary architectural design; what Zevi defined as “Mexican Grotesque.” In this paper, we will examine the political context of Post-Revolutionary Mexico and discuss what may be defined as its most iconic building; the Central Library at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico. In direct counterpoint to Zevi, we will suggest that it was far from grotesque, but rather was one of the most committed political statements made by the Modern Movement throughout the twentieth century. It was propaganda, it was political. It was utopian.

The political backdrop to the artistic and architectural revolution of twentieth century Mexico

The history of Mexican architecture is of course a long, rich and deep rooted phenomenon that has given the world numerous “styles” of ancient architecture; generally associated with its diverse Pre-Columbian heritage.2

The Pre-Columbian heritage of Mexican architecture can be found in numerous texts. The civilizations most commonly considered under this title conclude the Olmec, the Teotihuacan, the Maya, the Toltec and the Aztec. Typical reference texts include Ignacio Marquina, Arquitectura Prehispánica (1964); Paul Gendrop, Compendio de Arte Prehispánico (1988); De Robina, Arquitectura Prehispánica (1969); Gene S. Stuart, America’s Ancient Cities (1988); Fernando R. Winfield-Capitaine, Pueblos Prehispánicos de México (1994); Alejandro Mangino Tazzer, Arquitectura Mesoamericana: Relaciones Espaciales (1990).

With the imperial domination of the country between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries however, the architecture of Europe superimposed itself on traditional forms of living at both an urban and individual level. With independence from the Spanish yoke in the early years of the nineteenth century, there followed a number of decades of political instability during which an internationally recognized and independent Mexico eventually emerged; albeit one seen as weakened by internal struggles and constant conflict with an expansionist United States. This state of independence was temporarily lost in the 1860s with indirect French rule through the figure of the Second Habsburg Archduke Ferdinand Maximilian. Once again, the architecture imposed on Mexico by its colonial masters was to be one that followed the European model and which can generally be described as Neo-Classical.3The history of Mexico’s Colonial architecture is equally well documented as its Pre-Columbian period. Typical in this regard are texts such as: Jesús T. Acevedo, Disertaciones de un Arquitecto (1967, originally published in 1920); Hans Beacham, The Architecture of Mexico: Yesterday and Today (1969) with an introduction by Mathias Goeritz; and Enrique X. de Anda, Evolución de la Arquitectura en México (1987). All of these texts are analyzed concisely by Louise Noelle, “Bibliografía Analítica,” in La arquitectura Mexicana del Siglo XX, ed. Fernando González Gortázar (Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1996), 485–517.

Although French rule in the nineteenth century was short lived, the preponderance for Neo-Classicism in Mexico continued during the next period of independence under the leadership of Porfirio Díaz.4

Porfirio Díaz was a former general during the French Imperial period who came to power after his involvement in the rebellions against the French. See: Juan Brom and Dolores Duval. Esbozo de historia de México (Mexico: Grijalbo, 1998). Also interesting from a historical perspective with a literary narrative is Fernando del Paso, Noticias del Imperio (2006, originally published in 1987). For books dealing specifically with the approach to architectural and city design during this period, see: Elena Segurajáuregui, Arquitectura Porfirista: La Colonia Juárez (1990); Ramón Vargas Salguero, ed. Historia de la Arquitectura y el Urbanismo Mexicanos. Volume III: El México Independiente. Afirmación del Nacionalismo y la Modernidad (1998).

Ruling between 1876 and 1911 the Porfiriato5The period of rule of José de la Cruz Porfirio Díaz was, in essence, a continual dictatorship. It became known as the Porfiriato.

oversaw a then unprecedented process of industrialization in Mexico which, once again, took as its models of development, culture and architecture, the European traditions inherited from previous Colonial powers. However, during the Porfiriato there was a noticeable emphasis placed on the incorporation of Pre-Columbian references into the then “contemporary” Neo-Classical architecture of the country.Consequently, what was to emerge architecturally from this period was not a clearly new architectural style that totally distanced itself from the past, but rather a timid move towards the recognition and celebration of Mexico’s past. This eclectic mix was perhaps most clearly seen in the Palace of Fine Arts and the unfinished Palace for Federal Legislators; both enormous projects designed by foreign architects. The first was the work of the Italian Adamo Boari and the second by Émile Bernard of France. The eclecticism found in their work was also evident to some degree in the modernization for the Port of Veracruz; a project developed by the English entrepreneur Weetman D. Pearson. As with the Europe of the time, although these works were challenging from a technical and industrial perspective, they were new constructions clad in the clothing of an historical style6

In this regard the architecture of Mexico perfectly reflects the “battle of the styles” evident in Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom.

which, in the case of Mexico, was associated with imperial domination.7For broad explanations of the role of foreign influences and architects working in Mexico before the Revolution, see: Ramón Vargas Salguero, “Las Fiestas del Centenario: Recapitulaciones y Vaticinios,” in La Arquitectura Mexicana del Siglo XX, ed. Fernando González Gortázar (Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1994), 19–33; Ernesto Alva Martínez, “La búsqueda de una identidad,” in La arquitectura mexicana del siglo XX, ed. Fernando González Gortázar (Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1994), 35-57; Luis R. Campa, “El Porfiriato (1902-1911),” in Imágenes de un Siglo de Historia Construida 1902-2002, ed. CMIC Delegación Veracruz (Veracruz: Delegación Veracruz de la Cámara Mexicana de la Industria de la Construcción, 2003), 12-33; Priscila Connolly, El Contratista de Don Porfirio: Obras Públicas, Eeuda y Desarrollo Desigual (Mexico: Colegio de Michoacán, Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Azcapotzalco and Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1997); Fernando N. Winfield Reyes, “En Torno a la Práctica del Urbanismo y la Adopción de Referentes Extranjeros en México 1876-2000.” Cuadernos de Investigación Urbanística/ Ci[ur] 47 (2006): 37-48.

There was not any great change in this situation until some years after Mexico’s next rebellion; the revolution that overthrew Porfirio Diaz and which is generally considered to be the first socialist inspired revolution of the twentieth century. The Mexican Revolution began in 1910 and lasted years in one form or another. Diaz went into almost immediate exile in France in 1911 and Francisco I. Madero assumed the presidency later that same year. However, Madero was later killed in a coup-d’état in 1913 and the country suffered yet another period of political instability.8

José Victoriano Huerta led a military coup against the elected government in 1911. He then ruled the country until Venustiano Carranza forged the “Plan of Guadalupe” with collaboration from rebel leaders including Emiliano Zapata and Francisco ‘Pancho’ Villa. After the struggles that followed Huerta eventually resigned the presidency in the summer of 1914.

This was finally put to rest with the passing of the 1917 constitution in which the government of Venustiano Carranza was installed on the basis of promises of drastic changes in the distribution of property and land, better employment conditions for the working class and noticeable improvements in the spheres of health, education and housing. 9This period of Mexican history gave the world the Revolutionary figures of ‘Pancho’ Villa and Emilio Zapata amongst others.

From this moment onwards the socio-political scenario that had conditioned Mexican architecture along Neo-Classical lines for centuries shifted significantly. The consequences in architectural terms however would not be seen until the 1930s and 1940s; a time defined in Mexican history as the Post-Revolutionary period.10

The term Post-Revolutionary’ refers to the period between 1921 and 1946 and is used to describe the political as well as cultural context of the country during this period. Architecture and the visual arts such as Muralism are defined by the same turn. In these cases, it is defined as continuing until the early 1950s when some of the nation’s principal modernist buildings and art works were produced.

Given the socialist leanings of the revolutionary leaders, and the political parties they eventually formed, the Soviet Union became an early model upon which the Mexican State sought to base itself.11Although the principle political influence throughout most of the Post-Revolutionary period was staunchly socialist (and generally associated with Soviet Union) from the mid 1940s onwards there was a shift to centre-right ideas and an increase in the cultural influence of the United States.

This was inevitably reflected in intellectual and artistic circles with artists, architects, writers and thinkers from across Mexico drawing inspiration, and directly seeking contacts, with the left-wing avant-garde ideas coming out of Europe and particularly the Soviet Union in the 1920s.Embracing the Modern Movement

In Mexico the Modern Movement, as with its Soviet manifestations, was seen as encompassing the expression of “a new aesthetic and technological utopia” that promoted social changes in line with the policies of the new political establishment. Consequently, the art and architecture of the period sought to combine political and formal ideas, and to instill a new artistic-political philosophy through theories, manifestoes and practical works. The influence of the left wing avant-gardes of Europe evident in these manifestos was to be reinforced by an influx of foreign figures into Mexico in the 1920s and 1930s; a phenomenon further reinforced by the willingness and ability of Mexican architects and artists to work abroad.

In this regard, there was a deliberate attempt to emulate the cross fertilization of ideas that was seen as taking place across the diverse artistic movements of Europe. The perception that Russian Constructivists, members of the Bauhaus, De Stijl and the Futurists for example, could all collaborate and learn from one another’s work quickly took hold in Mexico and wetted the appetite for cross cultural avant-garde influences.12

This history is of course well known and documented. It is mentioned here to highlight the overall context in which the Mexican art and architecture of the period operated.

It was seen to be one of the characteristics of the Modern Movement that made it “international” in style and scope, and was thus seen as in perfect accord with the cross national objectives of international socialism as practiced by the Mexican state in the political sphere.Another aspect of the Modern Movement to take hold in Mexico was the idea that design could be a phenomenon for the transformation of ways of living. This was to be operative at all its scales; industrial and product design addressing domestic needs was celebrated alongside the importance of architecture in improving living standards and, of course, the importance of urban design in the planning of cities and large regions. In this regard, the Athens Charter of 1938 in which CIAM put forward its “universalist” approach to city planning was well known and very influential in the Mexico of the period.13

See: Eric Mumford, The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928-1960. Foreword by Kenneth Frampton (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000), 59.

All these standard readings of the Modern Movement would influence Mexico in much the same way they would influence the United States throughout the 1920s and 1930s; through the dissemination of magazines and images but also through the emigration of key avant-garde artistic and political figures.The most famous intellectual to find a place in Mexico was of course Leon Trotsky. However, many other intellectuals and artists passed through the “new” socialist Mexico of the time. Not all of these figures were fleeing political repression; many were simply visiting one of the few countries of the period in which a new socialist and modernist utopia seemed a possibility. In all cases, the official government policy was to welcome the influx. Amongst the figures that came to Mexico at this time were Hannes Meyer and Mathias Goeritz from the Bauhaus; the architects Max Ludwig Cetto and Vladimir Kaspe, from Germany and the Russian enclave of Harbin respectively; key figures of Surrealism such as André Breton and Luis Buñuel; and the photographers Tina Modotti and Edward Weston. All these figures found fertile ground in Mexico and, in some cases, political refuge. They were key to the artistic and cultural development of the nation and, as a result, the “foreign” became a strong theme in the mindset of Mexican modernism.

During the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas del Río (1934-1940) and Manuel Ávila Camacho (1940-1946), the explicit policy of welcoming these people continued. There were a number of reasons. As with the early years of the Soviet regime under Lenin, the government saw avant-garde artistic ideas as a key way of distancing itself from the policies and imagery of previous regimes. On a more practical level, it was also assumed that these Europeans would bring knowledge of new cultural, scientific and political practices. Furthermore, in some cases (as with the Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel exiled from Fascist Spain) it represented a form of “ideological solidarity.”14

It was not just the influx of modernist architects and artists into Mexico however that played a part in this regard. The freedom to travel afforded to Mexican artists during this time was also significant as was the case for Diego Rivera who spent time in France, the Soviet Union, Spain and Italy. The most noticeable stylistic influence in Rivera’s work as a result of this was from Robert Delaunay. See: Frank Whitford, “The City in Painting,” in Unreal City: Urban Experience in Modern European Literature and Art, eds. Edward Timms and David Kelley (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1985), 45-64.

Opening its doors to political and cultural exiles, Mexico presented an international image of progressive and tolerant socialism. The embracing of the architectural, artistic and cultural ideas of Modernism then, also had a political aim.15A definition of these aims and their cultural implications are dealt with by Jorge Camberos Gabiri, “Hannes Meyer, su Etapa en México,” in La arquitectura mexicana del siglo XX, ed. Fernando González Gortázar (Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1994), 88-89.

It was not just a response to internal needs, and was not just for internal propaganda consumption, it was part of foreign policy.The politicization of modernism

What all this reveals is that from day one of the Post-Revolutionary period modern art and architecture in Mexico was supported by the government. At the level of infrastructure, it seemed to offer a form of construction that was both relatively quick and relatively cheap. Consequently, it could facilitate the type of nationwide construction programs seen as necessary to improve people’s lives and clearly establish the legitimacy and effectiveness of the new socialist governmental system. Throughout the 1930s and 1940s schools, hospitals, housing and large infrastructure projects were envisaged and, in many cases, even the most ambitious and speculative were actually realised. Whether built or not however, these projects were presented by the various manifestations of left wing parties emerging at the time, as socially progressive.

The political situation in which these architectural and urban projects were being envisaged was complex and it was not until 1929 that Plutarco Elías Calles founded the National Revolutionary Party (PNR), which encompassed what were up until that point a diverse range of factions. It was renamed the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in 1938 in response to further internal struggles regarding direction and policy. Despite the instability this level of political change produced, and despite the inevitable infighting that accompanied it, successive government administrations support and commissioned public projects which, in architectural and urban terms, were defiantly modernist and thus, symbolic of the Revolution.

Indicative of this embracing of modernism on a symbolic and practical level was the official welcome given to Hannes Meyer who first visited Mexico in 1938. Meyer was particularly influential due to his political stance and his insistence on architecture as a political tool. As not only a former leader of the Bauhaus, but also an architect who had participated in the first Five Year Plan in the Soviet Union, he was seen as the epitome of the architect-socialist. He was valued for what he represented but also for what he could do, or help to do, in terms of construction. On the practical level, it was assumed that he could advise on housing and city planning projects that would not only improve the lives of ordinary Mexicans but also function as symbols of the new government.16

The first years of Meyer in Mexico coincided with a time of great support for avant-garde social and left-wing artistic (and cultural) movements. In the final analysis however, the influence of Meyer was based on his theoretical stance and design proposals rather than his built work. Various obstacles were placed in the way of him realizing construction projects in Mexico, including personal rivalries. See Ibid., 86 and 93.

This politically and practically motivated acceptance of Modern Movement architecture by the government in Mexico opened the door to a group of young architects who were “fully enthused” with the social agenda and radical aesthetic of the Modern Movement.17

These architects saw themselves as “enemies” of the old aristocratic structures and of their forms of cultural expression. They were “addicted” to the postulates of Mexican Revolution and “enthusiastic” observers of the achievements of the First Five Year Plan’. See Enrique Yáñez, Arquitectura, Teoría, Diseño, Contexto (Mexico: Limusa, 1982), 176.

Amongst them were figures like Juan O’Gorman, José Villagrán, Juan Legarreta, Enrique Yáñez, Mario Pani and Enrique Del Moral18For a definition of their work, particularly that of O’Gorman, see: Xavier Guzmán Urbiola, Arquitectura Mexicana: Vivienda, Escuela y Hospitales (Mexico: Random House, 2008), 25-26.

; all of whom were in collectives such as the Union of Socialist Architects, and all of whom produced art works and political manifestoes as well as buildings. Early in their careers these architects participated in constructing different types of socially orientated government buildings; Villagrán built a rationalist-style hospital in Huipulco (1929); O’Gorman built schools on a low budget and proposed the ‘One Million Pesos’ schools program (1932)19This terms refers to the construction of 23 and renovation of another 28 schools by O’Gorman for the then Education Minister, Narciso Bassols. It was seen as a celebration of modernism’s “social” potential as the whole project cost less than one million pesos. It was also seen as a development of previous educational projects carried out by Carlos Obregón under the previous Secretary of Education, Vasconcelos. See Ibid.

; Yáñez designed worker’s housing and later specialized in modern hospitals while Pani would become the main promoter of high rise housing in the Centro Urbano Presidente Alemán (1947-1949).In his essay, The Labyrinth of Solitude, Octavio Paz deals with the relationship that formed between the successive Post-Revolutionary governments of the 1930s and this generation of architects and artists.20

See: Octavio Paz, ‘La “Inteligencia” Mexicana’ in El Laberinto de la Soledad. Volume 27. Lecturas Mexicanas. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1984), 135-155.

Underlining the contradictory nature of collaborations between government (and thus establishment institutions) and avant-garde artists, he points out that in Mexico the ‘contradiction’ was particularly noticeable; these ‘independent’ architects and artists actually becoming political advisers in both the public and private sphere. The intrinsic relationship that emerged as a result of this meant that the avantgarde in Mexico did not really play a role in socio-political criticism at the time, but rather became a ‘means of political action’’; an arm of government.The closeness of this relationship was evident in the official backing for artistic and intellectual groupings such as the Ateneo de la Juventud (The Athenaeum of the Youth),21

The Ateneo de la Juventud had over one hundred members and included writers, philosophers, musicians, painters, architects and engineers. It was operative between 1912 and 1914. One of their members was José Vasconcelos, later to be Secretary of Education in 1921 and Rector of the National Autonomous University.

the Contemporáneos (the Contemporaries),22This group was formed around a publication of the same name first published in 1928. One of their members, Jaime Torres Bodet, would later enter politics directly as Secretary of Education (1943-1946 and 1958-1964), Secretary of Foreign Affairs (1946) and General Director for the UNESCO (1948).

or the Estridentistas (the Stridentists)23The Stridentists were established in 1921 and later developed their work in the city of Xalapa. They were a collection of artists, thinkers and designers form different fields including: the poet Manuel Maples Acre, the painter Fermín Revueltas Sánchez, the print maker Leopoldo Méndez and the illustrator Ramón Alva de la Canal. They were influenced by Cubism, Futurism and Dada which they attempted to interpret in the Mexican context. See Germán List Arzubide, El Movimiento Estridentista (Mexico: Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1987), and also Silvia Pappe, Estridentópolis: Urbanización y Montaje (Mexico: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana_Azcapotzalco, 2006).

; organisations that were either established, or officially recognised, during this period. Of all of these, the Estridentistas were seen as the most radical and from their camp came projects such as the Edificio del Movimiento Estridentista (Stridentist Movement Building) by Ramón Alva de la Canal (1926) and the Estadio Modernista (Modern Stadium) at Xalapa, (1925) southeast Mexico; a building designed by Modesto Rolland and constructed in reinforced concrete. In both its elimination of ‘colonial’ classical motifs and its construction techniques, it was seen as a ‘model’; an icon of the progress of the Post-Revolutionary ideology.24For more information n this building, see: Lourdes Cruz González Franco, ed. El Estadio Olímpico Universitario. Lecturas Entrecruzadas (Mexico City: UNAM, 2007), 44; and Daniel Martí Capitanachi, and Fernando N. Winfield Reyes, “Interpretaciones Singulares de Visiones Colectivas: Estridentópolis,” in La Arquitectura Moderna desde la Calle: Un Recorrido de Ciudades Mexicanas, eds. Eloy Méndez et al. (Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, 2011), 303-317.

In the arts, this tendency was perhaps most evident in the government projects carried out by Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros and José Clemente Orozco; all of whom collaborated on important government works and supported the principal government message of the time. This message was also supported by women artists who, under the progressive policies of the Post-Revolutionary regime, also began to find openings and opportunities to establish themselves. Among the figures to receive recognition at this time were Antonieta Rivas-Mercado (a member of the Contemporaries), Naui Ollin (an associate of the Contemporaries, the Stridentists and the Surrealists)25

As with many of the male artists of the time Naui Ollin had travelled in Europe and had met with Pablo Picasso and Diego Rivera in Paris before 1921. The influence of these visits was evident in the work she did upon her return to Mexico.

, Tina Modotti (an Italian photographer who also worked with the Stridentists) and Frida Kahlo who, despite operating in the shadow of Diego Rivera much of her life, was also officially recognised in her own right.26Kahlo was categorised as a Surrealist painter, although her paintings are not easily classified and she relentlessly refused to accept the classification. See: Adriana Malvido, Nahui Olin: La Mujer del Sol (Barcelona: Circe Ediciones, 2003); Giovanna Uzzani, Surrealismo (Florence: Scala, 2011) and Rafael Vargas, “Repaso para Mirar la Exposición del Surrealismo.” Proceso 1868. August (2012): 68-69.

Receiving governmental recognition, albeit in a timid form initially, these female artists also became representative of the “new,” progressive socialist Mexico and reflect just one more way in which modern art and design tendencies took on symbolic importance for the Mexican governments of the time.The “new” Mexico: Post-Revolutionary tradition and modernity

The involvement of all these artists and architects in “modernizing” both the image and the infrastructure of Mexican life and culture was intrinsically linked with the aims of the government; to portray a progressive image internationally, to physically build a new Mexico, and to both construct and communicate a new identity for itself and its people; an identity linked to the rejection of the imperial past and the embracing of modernity. In a sense, this new national political identity can be defined as based on the standard modernist, proto-socialist ideology also evidenced in Post-Revolutionary Russia. Crucially, in Mexico however, it acquired a distinct hue based on a recuperation of long standing traditions and symbols.

In embracing modernization, the Post-Revolutionary ethos, perhaps contradictorily, also attempted to regain a grasp of Mexico’s Pre-Columbian roots. It could be argued that this dual futuristic and historical perspective was motivated by a desire to erase the intervening years of Colonial influence. More pragmatically perhaps, it may simply be read as an attempt by the government to distance itself, and the country, from the still latent memory of the Pre-Revolutionary government. Tied into this was the fact that after centuries of colonial rule, Mexican society was inherently hybrid; the Pre-Columbian heritage having lived alongside the Hispanic heritage for over four centuries. If a Post-Revolutionary government was to be a government for all, it would have to be a government of a diverse range of peoples and traditions. The creation of a political identity capable of balancing these factors would have to be one that celebrated and embraced diversity; an identity that celebrated the past while it looked to the future.

Nobody promoted this idea more forcefully or successfully than José Vasconcelos; the teacher, philosopher and education minister between 1921 and 1924. Vasconcelos was not only a respected intellectual who would publish treatises on subjects ranging from education to aesthetics, and genealogy to sociology, he was also a committed political activist and teacher. He taught at the best universities in Mexico and the United States and would be forever associated with the social philosophy of “indigenismo”; a series of arguments that promoted the social and cultural benefits of mixed races.

Upon leaving government in 1925 he would publish his most influential text; The Cosmic Race, in which he promoted the idea of the “fifth race” in the Americas; a cultural fusion of peoples for whom division along the lines of colour or creed had ceased to exist.27

See: Vasconcelos, 1997. (Original, 1925)

He postulated that indigenismo could lead to a new civilization that he defined with the term Universópolis. Although the ideas of Vasconcelos were never adapted explicitly as public policy, his vision of a progressive, inclusive and hybrid Mexico was to be the core of the “new identity” the Post-Revolutionary government was to attempt to build. Key to the construction of this new identity however, was its promotion to the people, and it was in this context that the architecture defined by Zevi as “Mexican Grotesque” was to emerge.Although the Post-Revolutionary government promoted all the arts, and saw each one of them as capable of communicating the government message, there was one particular art form that came to be considered of primary importance in this “communicative / propagandistic” context; the mural. The reason why murals became so important in Mexico at this juncture are found firstly in its public nature, and secondly, in the generally low levels of literacy still evident in Mexico in the early years of the Post-Revolutionary period. As Education Minister for example, Vasconcelos argued for a use of public art to convey political messages visually. As murals are inherently displayed in public, they were seen as ideal vehicles for the communication of the government agenda and, as such, one could argue that they took on a the role similar to that assigned to painting by the Catholic Church.

Although the three main figures identified with the Mexican Muralism are Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros, other painters were also involved including Ramón Alva de la Canal, Manuel Lozano and the architect of the building we will discuss in more detail later, Juan O’Gorman. These artists all gained significant government commissions and were famed for reinterpreting foreign avant-garde ideas and techniques in hybrid expressions of the modern mestizo Mexico; the image of Mexico promoted by Vasconcelos in particular, but also the government in general. 28

In Mexico the term “mestizo” is an imprecise term used to refer to mixed cultural, racial and biological notions. For a period it appeared on the Mexican censuses as an option for self definition.

Octavio Paz underlines the role played by Vasconcelos in the elevation of murals to a position of key political importance by identifying him as a figure central to the granting of major commissions.29

See: Octavio Paz, La “Inteligencia”, 11.

As a result of his intervention, nationalistic murals were painted on various public buildings including the National Palace, the San Ildefonso College, the Fine Arts Palace and the Secretary of Public Education building. In each case we see a celebration of the past and the present fused with the presentation of multiple cultures. In Rivera’s mural for the National Palace in the late 1920s for example, we have an epic representation of Mexican history and culture; native Indians, the Spanish conquerors and successive foreign forces including the French and North Americans are all depicted in a collage of life throughout the nineteenth and into the twentieth centuries.These features that combine the historic with the present, and the regional with the universal, can be seen as precursors to developments in the art and architecture of the Post-Modern period some thirty to forty years later. In a sense, they echo the ideas of critical regionalism, as put forward by Kenneth Frampton,30

See: Kenneth Frampton, Modern Architecture: A Critical History. 3rd edition (London: Thames & Hudson, 1992).

and the contemporary ideas of Post-Modern eclecticism,31These ideas attributed primarily to Robert Venturi and Charles Jencks were developed in the context of the apolitical United States. In Mexico the context was of course completely different and explicitly politicized. The use of the term in this context does not carry the pejorative and superficial connotations it tends to in North American context. Neither is it associated with a rejection of modernism. In the Mexican context it was a “political” rejection of the architecture of the late 19th century - seen in its day as “modern”.

that would come to dominate the arts and architecture scenes of the United States and Europe in the 1970s. In Mexico however, this celebration of varied cultural, historical and contemporary references was very different to the apolitical context in which it was to emerge in these countries. In Mexico, it was fully integrated into the politics of the state.In addition to the use of politically orientated murals on existing, and thus historic buildings such as the National Palace however, the coming years would see murals used on newer buildings. Typical examples in this regard include the covering of walls at the Gertrudis Bocanegra Library in Pátzcuaro, the use of modernist plain surfaces at Mexico City Airport and the incorporation of murals in a whole series of the schools designed by Juan O’Gorman in the 1930s as part of the “One Million Pesos” project. Murals would also be used on later modernist projects such as The Insurgents Theatre and The National Stadium; both modernist buildings from the early 1950s that carried murals by Diego Rivera.

In certain ways this mixing of modern architecture with Pre-Columbian imagery, symbolism and decoration through the mural echoed the tendencies of the government funded architecture of the Porfiriato and its own attempts at cross cultural eclecticism. There were two crucial differences however. Firstly, in the eclecticism promoted by the Post-Revolutionary government there was a rejection of the Colonial styles expressly associated with particular countries; France and Spain specifically. Such references were to be replaced by an architecture (and an art) that was seen to be “universal” or “international”; the abstract art and architecture of the Modern Movement. Secondly, the content of the art in question, and the intentions behind the architecture that carried it, were seen to be poles apart. In place of the “decadent” Neo-Classicism of the Porfiriato and its associations with imperial and class hierarchies, the art and architecture of the Post-Revolutionary government was geared towards the “betterment of the life” for the working class and the celebration of the efforts to achieve it.

Seen in this light, these projects are almost completely opposed to the art and architecture of the Porfiriato. They are Gesamtkunstwerk that represent a mixture of the modern and the historic, a fusion of one cultural tradition with another, and a combination of art and architecture intended to represent a completely new Mexico.32

See: Valerie Fraser, Building the New World: Studies in the Modern Architecture of Latin America 1930-1960 (London: Verso, 2000).

Clearly, the Gesamtkunstwerk was a perfect metaphor for the multi-faceted vision of culture and identity practiced by the government and, appropriately enough, it was an approach closely associated in Mexico with a mestizo figure; the Mexican artist of German dissent, Mathias Goeritz.33The integration of the arts was not a completely new phenomenon in Mexico. However, it did become an explicit objective during this period and took on its political hue. See: Enrique Del Moral, El Estilo: La Integración Plástica (Mexico: Seminario de Cultura Mexicana, 1966), 30.

Goeritz arrived in Mexico towards the end of the Post-Revolutionary period, 1949, and would die there over forty years later. He was hired by the Faculty of Architecture of the University of Guadalajara in western Mexico as a result of previous collaborations with Joseph Albers in the Bauhaus and a desire on the part of the Faculty director, Ignacio Díaz Morales, to promote the ‘integration of the arts’ ideas developed by the then iconic German school.34Goeritz is attributed as defining the School of Architecture of Guadalajara as a ‘Mexican Bauhaus’. See: Cristóbal A. Jácome Moreno, “Composiciones Visuales: Mathias Goeritz en Guadalajara.” Estudios Jaliscienses, no 81, 2010: 56-67.

By the late 1940s and early 1950s then, Mexico had produced a number of iconic buildings. In addition, some of its architects had become known worldwide and modernism had installed itself as the “national style”. However, it was a national style with a clear and marked difference from modernism as understood in the Bauhaus and across Europe. In the Mexican context, architecture was expected to be explicitly political. Its abstract forms were not always seen as formal ends in themselves but, more commonly, as vehicles for the promotion of the mixed message of hybridity, historicism and modernity enveloped in a socialist philosophy of industrialisation and equality. As vehicles for the presentation of this political message, they could struggle to work alone and it was for this reason that many of them were also expected to work alongside the art form that was most favoured by the government for its propaganda aims; the mural. The Gesamtkunstwerk, what Zevi referred to as the “Mexican Grotesque,” had definitively installed itself at the heart of the country’s architectural mindset. However, it had yet to produce its most powerful works.

La Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM): The “icon” of modern Mexico

For the various Post-Revolutionary Mexican governments there were numerous key objectives throughout the period from the 1920s to the early 1950s; building a health system, ensuring employment, ensuring political stability and improving education levels across the country. The driving force behind this educational concern was the one time Education Minister, Rector of the University and social philosopher, José Vasconcelos. On a personal level Vasconcelos believed in the potential of education to transform the nation, and thus placed it at the heart of his own political agenda; particularly when he himself stood for election as President in 1929.

However, even when Vasconcelos was out of government, education was a primary concern for the Post-Revolutionary governments of the period and central to their political program was a school building program. Included in that program was the construction of primary and secondary schools as well as university buildings. Juan O’Gorman, as with numerous other architects throughout the 1930s and into the 1940s, had been heavily involved in this construction program and had set the tone for “educational architecture” long before the construction project for the UNAM was first discussed in 1943.35

Among the earlier educational projects carried out by O’Gorman one finds: the Benito Juárez Primary School and Library (1924), the Amado Nervo Public Library (1922), the national School for Librarians and various children’s libraries at existing state schools across the country. For information on the educational policies underlying this, see: Martha Alicia Añorve Guillén, “Propuestas de Juana Manrique de Lara a la Política Bibliotecaria de Vasconcelos,” Investigación Bibliotecológica 20, no 41, July/December (2006): 63-90.

The University of Mexico was initially founded in the final months of the Porfiriato in 1910 and was envisaged, even then, as a symbol of modernity; it was to be a secular institution teaching the subjects deemed necessary for the 20th Century. It was however, to be under complete government control; a situation that did not change until the mid 1920s when, under the leadership of Vasconcelos and after numerous student protests, it became the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, UNAM.36

For a more detailed information, see: Juan B. Artigas, La ciudad universitaria de 1954. Un recorrido a cuarenta años de su inauguración (Mexico: UNAM, 1994).

In line with the philosophy of its then Rector, Vasconcelos, it adopted the motto; “The Spirit shall speak for my race.”When in 1943, under new leadership once more, and with the direct support of the government of Lázaro Cárdenas, the decision was taken to move the disperse university buildings to one site, the university campus would become the biggest single building project ever undertaken by the Post-Revolutionary government.37

The campus was the biggest single building project in Mexico since the period of the Aztecs.

It was also a project associated with one of their flagship policies; education. As a result, it inevitably became a symbol, the symbol, of the government and the modern Mexico it still sought to build.The campus, known as Ciudad Universitaria, was enormous. Located in San Ángel in the south area of the city, it occupied a site of two hundred hectares and was to be crossed by the symbolically named Insurgents Avenue. The inauguration of the construction process took place with much pomp and ceremony in 1952, with the then President Miguel Alemán Valés, present to witness the event in front of the press and the assembled public. The complex itself was the work of two of Mexico’s leading architects and urban designers; Mario Pani38

Mario Pani was a leading figure in Mexican architecture and urbanism. Numbered amongst his other major projects are numerous large housing schemes such as the Urban Center Presidente Alemán and Unidad Habitacional Nonoalco-Tlatelolco; the Normal School of Teachers and the National Consevatory of Music. He would also later found the National College of Architects (Mexico) in 1946. For more information, see: Louise Noelle, Mario Pani (Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2008).

and Enrique del Moral39Enrique del Moral was also a key figure in Mexican architecture. He designed and built more thanover 100 public and private projects would hold numerous offical and influential positons including Chairman of the Board of Architects of Mexico and the Mexican Society of Architects; Government buildings for the UNAM; Founder and member of the Academy of Arts and Fellow of the Bolivarian Society of Venezuela Architects and President of the Seminary of Mexican Culture, to name but a few.

. In addition to its various educational facilities, their scheme included a national sports stadium, later used as the Olympic Stadium in 1968, numerous theatres and various cultural centres.40These include UNIVERSUM, the Science Museum; the University Museum for the Sciences and Arts; the University Museum of Contemporary Art; the Teatro Juan Ruiz de Alarcón; Foro Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and the Centro Universitario de Teatro.

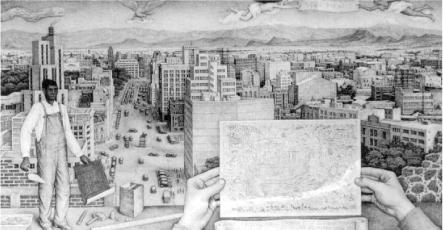

Following modernist urban principles, its buildings were grouped according to function and separated by expansive areas of public space. Most of the buildings however are relatively small scale with the exception of its two principle structures; the Rectorate Tower and the Central Library. The Rectorate Tower was designed Pani and Moral and is adorned by a mural by David Alfaro Siqueros. The Central Library, opened in 1956, was designed by Juan O’Gorman and would be covered by a mural of his own design.41

For a description of the history of the project, see: Edward R. Burian, “La Arquitectura de Juan O´Gorman. Dicotomía y Deriva,” in Modernidad y Arquitectura en México, ed. Edward. R. Burian (Mexico: Gustavo Gili, 1998), 143.

It is fourteen stories high, contains 428,000 books in its general stores and approximately 70,000 in its historical collection.42For discussions on the building itself, see: Jorge A. Manrique, “El Futuro Radiante: La Ciudad Universitaria” in La arquitectura mexicana del siglo XX, ed. Fernando González Gortázar (Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1994), 142-143.

It has 3,507 periodical titles, is the most important library in the country and, indeed, one of the most significant in the region as a whole.Although clearly “academically” significant, its function as a symbol of the Post-Revolutionary government is not played out at a programmatic or pedagogical level however. On the contrary, it is played out in the arena of its architecture, and of course, its fusion with the art of the mural. The building, as with those across the entire campus, is decidedly modern; a concrete rectangular block that dominates the site and the people around it. In and of itself, it is a typical of the symbols of industrialization and modernity central to government policy and their construction of political and national identity throughout the period we are dealing with.

Despite this however, its most powerful symbolic feature was the mural; and it was through this that it would take on its iconic status inside and outside Mexico, and through which, its “communicative function” would most clearly be played out. The mural itself, by then a standard feature of Mexican modernist architecture, was to be made of thousands of colored tiles; a technique that had never been applied on such a scale before.43

It was a mural technique that O’Gorman experimented with a few years before when working with Diego Rivera in his Anahuacalli studio during 1944.

It was to cover all four sides of the building and, in effect, turn the architecture into little more than a canvas for the presentation of a political message.44O’Gorman envisaged it as “a great unfolded canvas” that would allow the creation of “a didactic architecture; symbolic, allegoric and depicting mythological images and pre-hispanic motives”. It would be defined as “one of modern Mexico’s most important symbolic landmarks that reconnects with a mythical past for political purposes”. See: Burian, La Arquitectura de Juan O´Gorman, 144.

Such is the dominance of the mural here that the building completely disappears behind an all engulfing visual ensemble of symbolic decoration.45With its 4,000 square meters of stone covered almost entirely by this painting, it would be the largest mural in the world, becoming the symbol of the National Autonomous University of Mexico and its architectural insignia.

On the north wall O’Gorman envisaged a collage of Mexico’s Pre-Colombian past and uses motifs and symbols from different cultures in what amounts to a rough collage representation of an ancient Mexico City. By contrast, the south wall contains multiple references to Mexico’s colonial past, while the east wall is used as a canvas for the presentation of the international contemporary world of industrialization and urbanization. The west wall is a collage representing the university itself and the modern socialist Mexico. Despite its modernist underbelly and its “pragmatic function,” both political reflections of the progressive Post-Revolutionary government, it is also defiantly of the new mestizo Mexico. It is thus a reflection of government policy in both general and specific terms; a feature also reflected in the whole campus masterplan which, despite its inspiration in Modern Movement urbanism, has also been identified as making reference to pre-Columbian planning; a combination of open spaces populated with isolated buildings surrounded in general by natural landscape.

Conclusion: from the grotesque to the political

When we place the Central Library in the highly charged political context we have set out here, it becomes understandable why it was not only considered a material success by the government of the day, but also one of its most important propaganda achievements. In its very existence, it supported their argument that the Post-Revolutionary effort had responded to the very real educational needs of the Mexican Revolution. However, it also functioned as a symbol of a new and prosperous modern country. Furthermore, it was also the site of the city’s most impressive mural and thus represented the showpiece of the government’s open cultural and artistic agenda. Through the content of that mural, the government was also able to demonstrate, with the greatest clarity possible, its political aspirations, ideology and intended national identity.

Despite being heavily criticised as an absurd anomaly in the modernist / functionalist canon, as “Mexican Grotesque,” the Mexican Gesamtkunstwerk as represented by this building, was what had come to epitomise modern architecture in Mexico; at least large projects funded by the state.46

It should be noted that state housing projects in the “Modernist” style in Mexico do not necessarily carry political murals. It was a technique reserved for key and highly visible public projects.

In this context, architecture was called upon to do more than respond to practical or programmatic needs; it was called upon to help communicate a new national identity. In this scenario, functionalism could not be reduced to questions of program or construction. The function of architecture was to serve as a canvas for visible political symbolism.At the Central Library of UNAM, the politico-artistic image is superimposed on the architectural form with such force that we may say that the building’s ‘content’ (its thousands of books and reams of research material) and its programmatic objectives (supplying book storage and research space) are less important (less functional) than what can be seen on the surface. As with many examples of this typology in Mexico then, we are faced with a contradiction when considering modern architecture. The spatial properties, formal characteristics, programmatic intentions and, indeed, the inherently minimal aesthetic of the building are all identifiably “modernist,” however, they are pushed into the background by the superimposition of a form of surface decoration.

At first glance, it would seem that form and function are either separated or seen as unimportant. Their supposedly intrinsic relationship is continually called into question. However, if we consider the objective of the building, its “function”, in purely propagandistic terms, its “form” and “function” begin to resonate in perfect harmony. If we allow ourselves to read the building in its “communicative” terms, the flat, large faced surface that O’Gorman produced as an architectural form are perfectly functional and appropriate for the superimposition of his mural. The communicative message of that mural, as we have seen, was to present an “image” and an “ideal” to the Mexican people and to the world at large. It was intended to present Mexico as a mixed, and possibly therefore tolerant nation with deep cultural roots which, despite centuries of foreign intervention, had not been destroyed. However, it was also intended to present a modern image of Mexico as a prosperous, forward looking socialist nation; again to itself and to the outside world. In this regard, the function of the modernist and universal Central Library, and its hybrid and eclectic surface form “follow” one another perfectly.

When we examine Mexico’s most iconic modern building from this perspective, we cannot view it in only one regard. It may be a building that takes on all the traits of the Modern Movement in its materials, spatial layout, aesthetic treatment and construction methods, but it is clearly operating on other levels too. It is, in and of itself, representative of the political and social aspirations of the Post-Revolutionary period; as the University’s main hub, it symbolizes the belief of the new regime in the education of the masses and is thus inherently symbolic in essence. Superimposed on this however, is its other related function; its role as a canvas for a more specific and complex political message about Post-Revolutionary Mexican identity.

In contrast to the views of Bruno Zevi then, we suggest here that the building does not totally contradict the aims of the Modern Movement; perhaps too simply and readily defined as “functional” in very limited terms. On the contrary, once we allow ourselves to view the building as a site of propaganda, it becomes a building that can be interpreted in “communicatively functional” terms. If function is not reduced to purely material terms, the form and function of the building take on a symbiotic relationship much deeper than that of other ‘standard’ modernist buildings. As we have attempted to underline in this paper, the socio-political and historical context in which this building emerged not only makes such a reading possible but, we suggest, necessary and inevitable. Read in these terms it cannot be dismissed as “Mexican Grotesque”, but should be seen as a highly politically charged example of Mexican Post-Revolutionary modernism; a modernism that can only be fully appreciated in the context of a politically communicative function or, if one prefers, as utopian propaganda.

Bibliography

Añorve Guillén,, Martha Alicia. “Propuestas de Juana Manrique de Lara a la Política Bibliotecaria de Vasconcelos”. In Investigación Bibliotecológica 20, no 41, July/December (2006): 63-90.

Brom,, Juan and Dolores Duval. Esbozo de historia de México. Mexico: Grijalbo, 1998.

Burian,, Edward R. “La arquitectura de Juan O´Gorman. Dicotomía y Deriva.” In Modernidad y Arquitectura en México, edited by Burian, Edward R., 129-151. Mexico: Gustavo Gili, 1998.

Camberos Gabiri,, Jorge. “Hannes Meyer, su Etapa en México.” In La arquitectura mexicana del siglo XX, edited by González Gortázar, Fernando, 86-93. Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1994.

Cruz González Franco,, Lourdes, ed. El Estadio Olímpico Universitario. Lecturas Entrecruzadas. Mexico City: UNAM, 2007.

Del Moral,, Enrique. El Estilo: La Integración Plástica. Mexico: Seminario de Cultura Mexicana, 1966.

Frampton,, Kenneth. Modern Architecture: A Critical History. 3rd edition. London: Thames & Hudson, 1992.

Fraser,, Valerie. Building the New World: Studies in the Modern Architecture of Latin America 1930-1960. London: Verso, 2000.

Guzmán Urbiola,, Xavier. Arquitectura Mexicana: Vivienda, Escuela y Hospitales. Mexico: Random House Mondadori, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes and Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 2008.

Jácome Moreno,, Cristóbal A. “Composiciones Visuales: Mathias Goeritz en Guadalajara.” Estudios Jaliscienses 81 (2010): 56-67.

List Arzubide,, Germán. El Movimiento Estridentista. Mexico: Secretaría de Educación Pública, 1987.

Malvido,, Adriana. Nahui Olin: La Mujer del Sol. Barcelona: Circe Ediciones, 2003.

Manrique,, Jorge A. “El futuro radiante: la Ciudad Universitaria.” In La arquitectura mexicana del siglo XX, edited by González Gortázar, Fernando, 125-161. Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1994.

Martí Capitanachi,, Daniel and Fernando N. Winfield Reyes. “Interpretaciones Singulares de Visiones Colectivas: Estridentópolis.” In La Arquitectura Moderna desde la Calle: Un Recorrido de Ciudades Mexicanas, edited by Méndez, Eloy et al. Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, 2011.

Mumford,, Eric. The CIAM Discourse on Urbanism, 1928-1960. Foreword by Frampton, Kenneth. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000.

Noelle,, Louise. “Bibliografía Analítica.” In La arquitectura Mexicana del Siglo XX, edited by Gortázar, Fernando González, 485-517. Mexico: Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes, 1996.

Noelle,, Louise. “La Arquitectura y el Urbanismo de Mario Pani: Creatividad y Compromiso.” In Modernidad y Arquitectura en México, edited by Burian, Edward R., 179-191. Mexico: Gustavo Gili, 1998.

Noelle,, Louise. Mario Pani. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2008.

Pappe,, Silvia. Estridentópolis: Urbanización y Montaje. Mexico: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana Azcapotzalco, 2006.

Paz,, Octavio. ‘La “Inteligencia” Mexicana’ in El Laberinto de la Soledad. Volume 27: 135-155. Lecturas Mexicanas. México: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 1984.

Uzzani,, Giovanna. Surrealismo. Florence: Scala, 2011.

Vargas,, Rafael. “Repaso para Mirar la Exposición del Surrealismo.” Proceso 1868. August (2012): 68-69.

Whitford,, Frank. “The City in Painting.” In Unreal City. Urban Experience in Modern European Literature and Art, edited by Timms, Edward and Kelley, David. Manchester: Manchester University Press. 1985. 45-64.

Yáñez,, Enrique. Arquitectura, Teoría, Diseño, Contexto. Mexico: Limusa, 1982.

Zevi,, Bruno. “Grottesco Messicano.” In L’Espresso, December 29, 1957: 16. Reproduced in Arquitectura México 62, 1958: 110.

Footnotes

-

Zevi’s comments were made in reaction to an exhibition of Mexican architecture held in Rome, 1957. He criticized the mixture of modern forms with pre-Columbian motives typical of much of the work produced during the Post-Revolutionary period and, of course, the most iconic example of that tendency, the Central Library by O’Gorman. He defined this typology as ‘Mexican Grotesque’. He put forward this argument in an article originally published in L’Espresso, December 29 (1957), 16. It was later reproduced in the most famous journal of architecture in Mexico at the time: Arquitectura México, no. 62 (1958): 110.

⮭