Introduction

The Spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people, mediated by images.1

Hong Kong is known as a city with glitzy, towering skyscrapers. Victoria Harbour, reminiscent of a postcard image of Hong Kong with spectacular views of the city’s iconic buildings, has witnessed a massive transformation in recent years – large media walls have occupied the façades of many buildings. The cityscape now has dynamic information visible as a new urban skin. Beyond the postcard views of the skyline, zooming in at a street level, one can see digital screens of different shapes and sizes dotted around every corner. Media façades integrated with architectural structures are prevalent, significantly interlinking ‘architecture, media, space and message’ – a hybrid ‘mediatecture’2 constantly morphing into a spectacle across people’s everyday lives in Hong Kong.

This article takes as a case study Artificial Landscape, a site-specific media art project presented by the Sogo department store and Videotage.3 I was invited by both parties to curate several video works on CVision in March 2019; a 1400 square-metre LED screen equivalent to five full-sized tennis courts mounted on the façade of the department store.4 It is Asia Pacific’s largest LED outdoor screen. It is located in the heart of Causeway Bay,5 one of the busiest shopping districts, which is also the world’s most expensive shopping street in rent per square feet.6 It attracts 11.7 million viewer impressions per month.7 Therefore, the screen mediates a complex relationship between architectural structures, media and social life. It becomes a unique case for an artistic project and screen-based public art in the city.

Like many public screens in Hong Kong, CVision normally showcases various forms of advertisements. For example, the screen once featured a model’s face for a Japanese cosmetic brand. The hard-to-miss visual spanned seven floors of a building, resembling the sci-fi future portrayed in Blade Runner,8 the powder-white geisha’s face on a digital billboard in the film becomes the epitome of a sprawling cityscape based on late capitalism. In Causeway Bay, public screens showcasing commercial products have become a significant part of shopping malls, subway stations and various retail spaces. The everyday life of Hong Kong residents is enveloped with images of products. The media screens represent a potent visual symbol of Hong Kong as a financial hub, a landscape reinforcing consumerism as a core value in the city. Beyond commercial products, many companies and government bodies have also used public screens to construct a collective identity in recent years. Indeed, China and Hong Kong’s flags are constantly illuminated with LED lights on buildings on both sides of Victoria Harbour. Occasionally, CVision presents government advertising campaigns to reassure a coherent value of place while addressing certain political goals.

This article is divided into three parts. The first revisits the context and curatorial process of Artificial Landscape by drawing on the preparation of the project and interview with Jesse Liu, who was the head of Sogo Arts and Culture. The project represents a shift in practice from curating an exhibition in a white-cube space towards a community-oriented public project. Therefore, this part illustrates how Artificial Landscape adopts strategies to embrace a new form of spectatorship in public space. The second part focuses on the interviews with the four artists involved in this project. This part exemplifies how art can explore the subversive potential and create new contexts for urban spaces by illustrating the artists’ concepts, including critical reflection on issues surrounding surveillance, consumerism and rapid urban growth. Beyond the curatorial and production process, it is particularly crucial to consider how the public perceived the screen during the month-long project. The article’s third part draws on observations at the site. It illustrates how the project has introduced new modes of social interaction. Freedom in public spaces has been dramatically shrinking in Hong Kong. This article highlights how Artificial Landscape offers insights on how art’s presence in urban spaces can remediate a new reality – a break from the highly controlled and hyper-consumerist environment – and subsequently engage the public in an alternate reality that promotes civic creativity.

Context and curatorial process: the politics of urban space

I was invited by Jesse Liu, the former head of Sogo Arts and Culture, to explore using CVision in an artistic context in October 2019. Sogo is one of the largest department store chains with numerous branches in Japan. Since commencing its operations in Hong Kong in 1985, the store has become a retail landmark. In 2000, it was acquired by Lifestyle International Holdings, a company owned by local business magnate Thomas Lau.9 Since then, the store remains one of the busiest and most profitable in Hong Kong. Sogo established a new department specialising in cultural projects in 2019. Artificial Landscape is the debut project for the newly established department.

In a recent interview, Liu indicated that Sogo has been increasingly interested in art because of the company’s ambitions for another significant real estate project. In 2017, Lifestyle International Holdings bought a large piece of land at Kai Tak, the site of Hong Kong’s former airport and one of the city’s last pieces of prime land. Sogo plans to build the city’s first iconic twin towers and art-themed department store to house several large-scale commissioned artworks within the mega-redevelopment plan, consisting of retail, office, entertainment, cultural and housing units.10

In recent years, displaying famous artwork has become an indicator of a quality real estate project. Many companies combine art and commerce in their real estate projects. One notable example is K11, a museum and mall hybrid. Its founder, Adrian Cheng, calls it ‘the Silicon Valley of Culture’.11 Over the past few years, Cheng has worked with many notable curators, artists and institutions, such as Hans Ulrich Obrist, Serpentine Galleries, New Museum and MoMA PS1. His lifestyle retailing strategy includes opening 38 new branches of art-themed malls across China by 2024.12 Many art exhibitions will take place inside Cheng’s new shopping malls and real estate projects, presenting a popular approach to contemporary art.

Before joining Sogo, Liu worked at K11, gaining significant experience in incorporating art into malls as a marketing strategy. Sogo wanted to leverage the store’s mega screen to raise the brand’s values since the Kai Tak project was still in its early stages. The company was rebranded by foregrounding arts to pave the way for developing the future project at Kai Tak. The initial idea of using the mega screen was highly market-driven, yet motivated by a desire to draw attention to the building via the presence of art – an ideology similar to the conditions of neoliberal capitalism, in which the value of art is increasingly marked by commodification and the dominance of market-driven calculations. The free market is approached as a public arena, examined through the possibilities of knowledge production and sustained by economic interest.13

As a company listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, Lifestyle International Holdings was selective in choosing a partner to present the programme. ‘It was clear that Sogo did not want to exhibit political works or sexually explicit images. It was also why we wanted to work with Videotage, with whom I previously collaborated when I was working at K11. Ultimately, it is important to work with organisations that are easy to work with’, said Liu.14

In recent years, under the backdrop of the rising political tension in Hong Kong, exhibiting public art with political connotations has drawn great attention to the government. The government often takes a cautious approach in defining what is permitted to be exhibited in public space. For example, Human Vibrations, an exhibition presented by the government’s arts council, taking place on the LED façades of Hong Kong’s tallest building, the International Commerce Centre, raised great concern for freedom of expression and art in public spaces in 2016. The conceptual Countdown Machine, representing the end of ‘one country, two systems’, was suspended before the opening of the exhibition.15 Before this incident, the Countdown Machine’s artists, Sampson Wong and Jason Lam, installed an outdoor projector to project blessing messages on the façades of the government’s headquarters during the 2014 Umbrella Movement. Both artworks used building façades to present critical social issues, drawing connections between art and activism against the backdrop of heightened political awareness in Hong Kong.

As a consequence of taking down the Countdown Machine, the International Commerce Centre owner, Sun Hung Kai Properties, stopped inviting artists to use the exterior of the building, leaving its once successful award-winning light show to float with moving clip arts and tacky greeting messages ever since. Liu invited me to submit a proposal to the steering committee of Sogo in December 2018. As the curator of the project, I was well aware of the political dynamics of presenting artwork on a public screen, yet hoped to open certain possibilities for artistic interventions.

I went to the site regularly and familiarised myself with the culture every day. Under the skyscrapers and in front of the store, I saw trams crisscrossing between a flow of people and cars. Observations were taken on the street’s design, pedestrians’ behaviour towards the screen and the hive of activity taking place in the neighbourhood. The repeated field visits indicated that the unwritten social rule to survive in the neighbourhood is to keep moving – within a high level of unpredictability, one can also find moving as a synchronised rhythm that coordinates everyday life on the street.

A screening video works in a white cube or black box, where viewers are conditioned by cinema or gallery settings. In contrast, the viewing experience on a public screen sees a displacement of moving images from a linear cinematic configuration. Pedestrians are always in flux. Therefore, choosing certain artworks was not directed by the artwork’s immediate concern but to acknowledge that there was no single perspective to view art in such a context. As such, I consciously addressed the importance of making sense of the site’s situational nature in the curatorial process. I selected four video works produced by Shi Zheng, Carla Chan, Howard Cheng and Lawrence Lek, respectively, by January 2019. The curatorial process was developed interactively to allow the artists and me to critically exchange ideas about the spatial environment where the works were to be displayed to disrupt taken-for-granted ways of showing video art. A bricolage of a human-made environment characterised by excessive use of technology was implemented to embrace Causeway Bay’s unique environment. I also decided to use the title Artificial Landscape.

Concepts: different forms of artistic intervention

Artificial Landscape was launched in March 2019. Four video works were screened in the first three minutes of every hour during the whole month. At the premiere, the site became a panorama simultaneously virtual and real when looking at the four works on the mega-scale public screen, as if it was a public gallery. During the production process, ongoing conversations between the artists and me shed light on how certain artworks could create a break from the existing urban environment and allow the public to communicate through a remediated landscape. This section highlights my conversations and post-project interviews with the artists and illustrates how each artist has turned their ideas into an artistic intervention.

Shi Zheng: a landscape in between virtuality and reality

Shi Zheng’s Embers is an adaptation of a work originally commissioned by the Shanghai Biennale in 2016 (see Figure 1). This work’s inspiration is the artist’s personal experience in the virtual world of Second Life, an online game where users act as avatars and navigate virtual meeting places. Instead of socialising with other users, Zheng enjoys going to places where no users are present. Spending time in the abandoned places in Second Life gives him a sense of absolute solitude. Unlike the conventional beauty of civic places, he feels like he could find his authentic self in a deserted and unknown environment. Zheng has been collecting images and sounds from his virtual world journey for years. In Embers, Zheng uses the noise collected from his favourite spot in Second Life and processes it with algorithms written in software.16 In the final work, Embers transforms the noise collected into abstract black-and-red sceneries resembling pyroclastic molten rock streams. The sceneries are divided into six horizontal planes, each of which asynchronously flows at apparently random speeds.

I began the project by taking photos and collecting sounds in Second Life a few years ago. I have a collection of images and sound clips. Then I started to think about how to make use of them. For me, Embers is like a moving Barnett Newman painting, it is also about digital sublime.17

Abstract expressionists’ interest in myths and human consciousness makes them think about how the art style’s visual and philosophical implications can be applied in digital animation.18 For Zheng, the core idea of abstract expressionism can be articulated through the application of technology. He applies the automatic and subconscious process of art creation to examine the notion of the digital sublime, a concept proposed by scholar Vincent Mosco. In The Digital Sublime: Myth, Power, and Cyberspace, Mosco explores the notion of how contemporary societies are compelled to believe in myths surrounding new digital technologies.19 In contemporary art, artist Elwira Skowrońska borrows the concept and produces images with algorithmic technologies, depicting film representations of spaces impossible to create without recent coding techniques.20 Inspired by Mosco and Skowrońska, Zheng seeks to examine the distinctions between appearances and received interpretations by generating a realistic landscape that only exists digitally.

I found it interesting that the landscape portrayed in Embers is very realistic but also uncanny. Audiences can see the details of the landscape I created very clearly, but it is ultimately generated by computer programs … To put Embers at Sogo is particularly interesting. You know there is a real tree standing in front of the screen showing my animated landscape. I thought the imagery was very intriguing. It was a real mixture of the virtual and the real.21

Embers questions whether a non-physical space generated by a computer constitutes a reality, despite being perceptible by human optics. Situating the work in the urban context where hyperreal images, such as advertisements and news, are ubiquitous and more real than reality itself, Zheng seeks to create an environment that is simultaneously substance and human-made, a spectacle capable of blurring reality and simulating reality.22

During the monthly exhibition, one could feel the massiveness of Embers when looking at the screen from the Hennessy Road. It consumed a significant amount of space, enveloping the entire neighbourhood and its visitors. The scenic backdrop consisted of bright red colour, reflecting towards the road, trams and cars. Despite the massive screen, pedestrians’ perceptions of Zheng’s work were partial. Zheng notes,

In Second Life, the mouse and the keyboard are an extension of my body to navigate. In Artificial Landscape, the difference is that the pedestrians could never see the work in full because of the massive scale of the screen … Interestingly, they might see the reflection of the bright red colour of my work on their phone and they would then look up, and they see my work on the screen.23

Indeed, pedestrians’ sensory perceptions of Zheng’s work were not directed towards discrete objects, colours or shapes but arose from ‘a sense of atmosphere’.24 Considering the divided attention of pedestrians crossing the busy street and many factors affecting their actions, the viewing experience in such a context is always partial, encapsulated in the dynamic activities that take place at the site. While images morphed into the building’s surface during the exhibition, they were being transformed into something else – an aesthetic meaning mediated by fragments of the artist’s projected reality and illusion.

Carla Chan: a feeling of tranquillity in disorder

Like Zheng, Carla Chan uses computer software to create a simulated natural landscape in her work Black Move (see Figure 2). She wants to give the audience an extraterrestrial journey by immersing pedestrians into an abstract spherical space. ‘I am interested in the concept of chance and randomness. I thought anything created in the natural world is a result of randomness, and randomness represents something that is impossible to be created by human.’25 Chan deliberately created her work randomly throughout the production process of Black Move. By using 3D animation software Cinema 4D, Chan created noise particles resembling aesthetic patterns found in nature. Following this, she set a specific algorithmic parameter, subjecting the noise particles to random spatial and temporal variations so that she could produce dramatic effects on spreads and speeds.26 As one further examines Black Move, the animation’s apparent randomness also coordinates with an underlying pattern within the dynamic landscape. Chan uses it as a metaphor to represent the built environment in Causeway Bay – a cityscape that seems chaotic yet arranged in a hidden order, where actors, locations and architectures are constantly renewing themselves in a self-generating process.

Even though Chan and Zheng both created their animations using algorithms, their intentions of presenting abstract landscapes at Sogo are vastly different. Instead of creating an illusion of the real and virtual as in Embers, Chan seeks to create resistance to the built environment and inspire pedestrians to search for an alternative sensibility within reality.

Because the screen serves a very commercial purpose, my initial idea is to offer something that is not there. The pace of Black Move is very slow; it takes time to digest. I want the pedestrians to give time to watch my work so that they could feel the contrast between Causeway Bay and my world.27

At Sogo, the built environment is organised symbolically and narratively around consumerism. Like many urban centres, advertisements presented on public screens represent the logic of ‘semiocapital’ – human sensibility involved in the consumption of data, signs and symbols.28 Values are constructed by information technology and networked productivity. The pace of Black Move contrasts the city’s fast-paced rhythm. It disrupts the ‘continuous excitation’ and ‘mental environment’ normally shaped by the Causeway Bay screen.29

I would call the viewing experience of my work ‘trippy’. It is like the moment when someone slows down, picture the universe and imagine something out of what he or she usually thinks. As a Hong Kong person, my brain is always occupied by unnecessary information. My piece is contradictory to Causeway Bay. I want to offer the pedestrians a moment of stillness.30

On some occasions when Chan visited Causeway Bay during the month-long project, she observed many pedestrians caught by her work, not because of visual bombardment, but a sense of tranquillity. For many Hong Kong people, her work provides an alternative to the desensitisation of advertisements on public screens. Black Move is like therapy for pedestrians, to restore a sense of wholeness under the backdrop of the highly commoditised lifestyle, as if there is a way to feel tranquillity in disorder. Black Move helps construct a different atmosphere in Causeway Bay, directing an alternative form of imagination for those who participate in city life.

Lawrence Lek: a question about now and the future

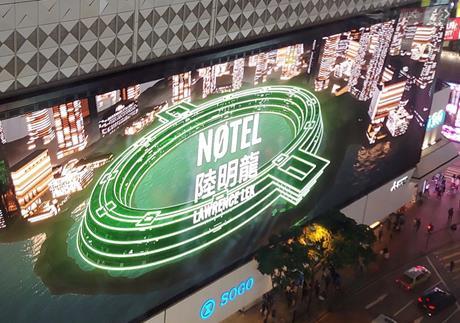

While Zheng and Chan intentionally replace advertisements with abstract landscapes in their works, Lawrence Lek satirically plays with the fact that Sogo’s public screen is used primarily for advertising. In Artificial Landscape, Lek presents Nøtel, a work that resembles a television commercial set in the future (see Figure 3). Nøtel is a simulation of a fully automated luxury hotel. According to Lek, the hotel is a machine, where artificial intelligence workers do the chores, and guests are constantly under surveillance from advanced technologies during their stay. The first version of Nøtel was presented as an audiovisual performance in two music festivals in 2016 and 2017. Since then, Lek expanded the work to different versions at arebyte Gallery in London and Stroom den Haag in the Netherlands. The one presented in Artificial Landscape is produced with imagery drawn from installations mentioned above and re-rendered as a super-widescreen advertisement.31

According to Lek, Nøtel represents ‘sinofuturism’, a term representing a future world when artificial intelligence takes over ‘flows of populations, of products, and of processes’32 with the aid of China’s advanced technology.

I see so many parallels between artificial intelligence and Chinese labour. For example, in Western news outlets, from Infowars to Fox News, the arguments against automation and artificial intelligence are the same as those against globalisation and China – ‘They’re stealing our jobs’, ‘They work for less pay’. Also, I thought that the computers used for deep learning research and the nameless Chinese workforce have much in common: programmed for endless work.33

Lek equates artificial intelligence with China’s rising economy, reflecting on the current power relations crisis embedded within globalisation and standardisation.34 For him, presenting Nøtel in Causeway Bay is particularly meaningful. It echoes to the notion of ‘sinofuturism’. In Causeway Bay, a retail landmark filled with consumer products is an epitome of laissez-faire capitalism. Since Hong Kong’s 1997 handover to China, the city has become a prominent intermediary city for technology exchange and commodity transaction between China and the rest of the world. In this context, Nøtel subtly raises a timely question of Hong Kong’s future – will the increasingly closer financial and political linkage to mainland China live up to the promises of a utopic future, alongside China’s role as a global technology leader? Lek added:

In older forms of science fiction, there is often a critical worldview – either they presented alternative or dystopian or apocalyptic futures that humanity should divert from, or offered fictions where artificial boundaries like gender, or race, or class were broken down. I think this critical worldview is still present in science fiction today, but now that the rate of change is much faster, and technology pervades and even accelerates so many developments, it becomes even more crucial to think about these critical worldviews are no longer black and white but much more complex.35

The scenario envisioned in Nøtel teases Hong Kong’s conflicting political nature in a technology-infused neighbourhood, creating a present that is far more out there than the existing settings in Causeway Bay.

Howard Cheng: a reflection on the post-panoptic city

Beyond animations, Artificial Landscape also presented a documentary shot by drone. In O, Howard Cheng uses several drones to capture an aerial view of Hennessy Road (see Figure 4). The three-minute flyover video of Causeway Bay reveals the unique pattern and movement of city dwellers. The video begins with a mass of cars moving on Hennessy Road in a mirrored manner as if they are being pulled together into a hole. When the cars stop at traffic lights, large groups of pedestrians start to dart across the road. Within a minute, a special effect appears as lines and dots connecting the pedestrians one by one. The effect is produced via visual tracking technology. As the pedestrians are in flux, the graphic looks like a spider making spiral orb webs, but constantly changing in shape.

My initial idea was inspired by the fact that Hong Kong is a place with a very high density of population. I once heard research saying that people’s comfortable distance with strangers is around 1.2 metres. In Hong Kong, it is impossible for strangers to keep this distance on the streets. Although we are physically close to each other, the emotional bonds between us are, however, low. I want to reflect this notion in my work.36

Cheng describes his experience of living in Hong Kong as being comparable to living in a cage. He elaborates this visual by using the example of railings as barriers on the streets.37 In Causeway Bay, one can easily notice that sidewalks are lined with railings. The ubiquitous fences lead to a drastic reduction of usable area in the urban space. On normal days, many of the railings are designed to direct pedestrians to retail spaces. On occasions such as public rallies, the railings are also used to reduce traffic flow and prohibit people from gathering in the streets. ‘In Hong Kong, urban design is not so much about people. In such an environment, we don’t have the space to imagine, and it really affects our bonding with other people’, continued Cheng.38 In locating O on the screen in the most densely populated place, Cheng wants to bring pedestrians back to ‘reality’ and encourage them to reflect on how the highly controlled urban environment has become an inescapable part of their everyday life.

Beyond critiquing urban design in Hong Kong, another issue evident in the work is the surveillance network in the city. ‘The repression Hong Kong people face is not only from physical restrictions but also on a mental level … Surveillance cameras are installed everywhere. We are so passive, and there is no escape’, continued Cheng.39 According to an article in the South China Morning Post in 2014, there are more than fifty thousand CCTV cameras over Hong Kong’s sky.40 Hong Kong residents are increasingly concerned about their privacy being compromised. Throughout the project, many pedestrians constantly looked up to the screen trying to make sense of O and wondering if they were being recorded in real time. While the pedestrians appear to be under surveillance and projected onto the screen, Cheng queries whether Hong Kong residents live in a post-panoptic urban space.41

Observations: spectatorship and situational awareness

During the project, Liu and I regularly went to the site to observe how audiences reacted to the screen. In a typical day, one could find pedestrians constantly finding their way around and in a hurry. At times, some pedestrians stood still and watched the works, while others took a fleeting glimpse at the screen as they were waiting for public transport or moving between places. The bulk flow of pedestrians moved swiftly, with many activities under the massive screen’s backdrop, constituting a complex spatial phenomenon during the monthly project.

Based on the site’s field observations, there were a few spectator types simultaneously getting on with their urban life while experiencing the contents presented on the screen. First, the screen tended to be viewed most by pedestrians waiting for a green light on the crosswalk’s opposite side. Whenever traffic lights on Hennessy Road turned red, these pedestrians stood idle. It was a transitional moment when they were transiently drawn towards the screen. The second type of spectators were those who rushed through and were not aware of the screen’s presence, until their attentions were captured by a sudden change in the screen’s imagery. Regardless of their intense or gentle ambience, unexpected atmospheric changes garnered these pedestrians’ attention, despite them being on the go. The third type were those located in the buildings surrounding the screen. The screen is on a massive scale; therefore, the surrounding buildings became a perfect spot to view the artworks. At Hysan Place, a shopping complex with expansive glass windows located opposite Sogo, commuters on escalators, foodies in restaurants and shoppers at storefront windows were drawn to the screen. Beyond the above, peer influence also appeared as a factor determining when and where pedestrians looked at the screen. On 30 March 2019, Videotage and Sogo organised a guided tour. A group of twenty audience members, including myself, listened to wireless headphones standing across the road. As soon as the group gathered, many pedestrians turned their heads to examine what the group was watching. In time, they realised it was an art show. Some tagged along, and the rest started to take selfies, immediately posting them on social media. This type of spectator was influenced by others’ behaviours and actions as if they were conforming to an implicit social norm on the street.

All in all, the project offered a renewed spatial experience that disrupted the initial functions and activities prescribed in various places surrounding the screen. Regardless of whether the spectators were waiting for a traffic light, rushing through the road, dining in a restaurant in the opposite shopping mall or tagging along with the guided tour, their viewing experiences were framed somewhere between ‘here’ on the ground and ‘elsewhere’ on the screen.42 In Causeway Bay, these spectators were simultaneously audiences, performers and co-producers of the event, rendering a ‘situational’ picture – the consumption of the screen was mediated by the immediate circumstances.43 The mutually constitutive relationships among the public, architecture and public screen formed a unique atmosphere, where the actions, decisions and perceptions of the pedestrians were constantly in flux. As the screen’s surface flickered, these pedestrians were momentarily drawn into the city’s perceptually shifting landscapes.

Conclusion: art’s role in creating a broader public sphere

In Hong Kong, beyond a cityscape containing buildings mashed together with incredible density, the public space experience is increasingly permeated by screen technologies, where ‘spatial experiences of streetscape and datascape’44 are intertwined. The real estate’s urban design informs a broader social fabric of society indicative of a capitalist-driven mentality, infiltrating Hong Kong residents’ everyday experience. Artificial Landscape, a project that remediated the context in Hennessy Road, has offered certain insights into the public screen’s mode of spectatorship, public space quality and curatorial strategies in the urban context. There are three possible points of relevance to consider from the project.

In terms of the public screen’s spectatorship mode, this project created a renewed atmosphere in Causeway Bay, where four entirely different landscapes temporarily enveloped the pedestrians. The colour, composition, flow, rhythm and content of the artworks formed a picturesque backdrop on Hennessy Road, casting reflections onto the road and surrounding buildings. The project offered multiple unique perspectives and consciousness for the public from ground level looking up or thousands of feet above. During the project, urban life was extended across multiple spatial and temporal encounters on the street, crisscrossing trams, cars and the flow of people. Pedestrians were collectively shaped by a distinctive mood, coordinated in a shared atmosphere. However, their experience was also mediated by an individual’s choice, interpretation and reflection within the collective experience. The coexistence of the screen, architectures and daily encounters ran alongside the artwork’s remediation of how various agencies provide new mutually constitutive relationships within an urban space. The performative possibilities elicited in this project evidence that art plays a prominent role in refiguring an individual’s sense of being.

Regarding the quality of public space and publicness, this project represents values largely absent in Hong Kong. During the month, the restrictive screen, which primarily functioned for commodity promotion, was radically transformed into an art project. This project reveals how a public screen can serve as a mediating agent for destabilising the capitalist mentality within the economic sphere. It offers artists an opportunity to provoke ideas absent in the public space and allows the public to participate in an alternative context where negotiations of perceptions and subjectivities are possible. Through an artistic intervention, Artificial Landscape reframed the relations between the built environment, media technologies, artists, public and everyday encounters towards a broader social and public sphere.

As for curatorial strategies, this project offered insights into mediations among artists, commercial ventures and the broader public. Real estate companies are increasingly interested in presenting art for commercial interests. However, the freedom to present certain political works in the city is dramatically shrinking, prompting the question of how a curator could tactically manoeuvre through webs of power to curate a meaningful public project. Suppose the public screen is part of the ‘strategies’ imposed on urban space, where certain political and economic rationalities are constructed with the artists and public. In that case, it should tactically create a space that belongs to the other.45 This project provided insight into how capitalising on art’s advantages and creatively developing new forms of experience remains vital in destabilising the ubiquitous power of the commodity spectacle and surveillance.

As this article was being written, Liu left Sogo, while the department store’s arts and culture division has also been shut down. A few months after Artificial Landscape, Causeway Bay became one of the major sites of the ongoing anti-extradition social movement. Simultaneously, another new screen has been erected opposite Sogo. All these show that Hong Kong is ever-changing; the city is contested as much as shared. The present is relevant for using art to intervene in public spaces, given that Hong Kong’s residents are living through a period of the most unprecedented changes in the city’s history.

Notes

- Debord, Society of the Spectacle. ⮭

- Lam, Scenography as New Ideology, 59. ⮭

- Founded in 1986, Videotage is one of the most active non-profit organisations in the region. It is dedicated to collecting and presenting political media works. Its collection contains works produced since the 1980s. It preserves many experimental videos addressing diverse political issues. ⮭

- See https://www.cvision.com.hk ⮭

- Ap, ‘Sogo department store’. ⮭

- Sito, ‘Causeway Bay’s Russell Street’. ⮭

- See https://www.cvision.com.hk ⮭

- Krajina, Negotiating the Mediated City, 23. ⮭

- Nason and Fernandez, SOGO, 2. ⮭

- Li, ‘Sogo operator lifestyle international wins’. ⮭

- Tomlinson, ‘100 creatives, 10 years, 1 vision’. ⮭

- Biondi, ‘Adrian Cheng’. ⮭

- Scholte, ‘Civil society’, 28. ⮭

- Jesse Liu, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Cheung, ‘Lights out for controversial 2047’. ⮭

- Shi Zheng, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Shi Zheng, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Shi Zheng, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Mosco, The Digital Sublime. ⮭

- See https://www.elwiraskowronska.com/bio ⮭

- Shi Zheng, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Baudrillard, Simulacra, 1. ⮭

- Shi Zheng, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Papastergiadis, Barikin and McQuire, ‘Conclusion’, 223. ⮭

- Carla Chan, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Carla Chan, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Carla Chan, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Cubitt, ‘ Defining the public’, 84. ⮭

- Berardi and Genosko, ‘BIFO’, 94. ⮭

- Carla Chan, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Lawrence Lek, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe, ‘Lawrence Lek’. ⮭

- Lawrence Lek, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Lawrence Lek, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Lawrence Lek, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Howard Cheng, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Howard Cheng, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Howard Cheng, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Howard Cheng, discussion with author, November 2020. ⮭

- Lam, ‘50,000 CCTV cameras in Hong Kong’. ⮭

- Basturk, ‘A brief analyse’, 2. ⮭

- Krajina, Negotiating the Mediated City, 146. ⮭

- Krajina, Negotiating the Mediated City, 41. ⮭

- Papastergiadis, Barikin, McQuire and Yue. ‘Introduction’, 22. ⮭

- Certeau, Practice of Everyday Life, 29–42. ⮭

Acknowledgements

This research is partially funded by the Subvention Fund of The Faculty of Arts, The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Declarations and conflict of interests

The author declares no conflicts of interest with this work.

References

Ap, Tiffany. (2017). ‘Sogo Department Store unveils APAC’s largest screen’. WWD, October 27 2017 https://wwd.com/fashion-news/fashion-scoops/sogo-department-store-hong-kong-largest-led-screen-apac-11036543 . Accessed 22 January 2020

Basturk, Efe. (2017). ‘A brief analyse on post panoptic surveillance: Deleuze & Guattarian approach’. International Journal of Social Sciences 6 (no. 2) : 1–17.

Baudrillard, Jean. (2019). Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Berardi, Franco; Genosko, Gary. (2011). ‘BIFO: After the future’. After the Future. Gary, Genosko, Nicholas, Thoburn Thoburn (eds.), Edinburgh: AK Press.

Biondi, Annachiara. (2021). ‘Adrian Cheng on Hong Kong growth, China’s future’. Vogue Business, January 13 2021 https://www.voguebusiness.com/companies/adrian-cheng-interview-k11-musea-hong-kong-retail . Accessed 28 June 2021

Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe. (). Lawrence Lek: Sinofuturism (1839–2046 ad). https://zkm.de/en/sinofuturism-1839-2046-ad . Accessed 28 June 2021

Certeau, Michel de. (2011). The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cheung, Elizabeth. (2016). ‘Lights out for controversial 2047 “Countdown Machine” art installation on Hong Kong’s ICC building’. South China Morning Post, May 23 2016 https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/education-community/article/1951495/lights-out-controversial-2047-countdown-machine . Accessed 22 January 2020

Cubitt, Sean. (2016). ‘Defining the public in Piccadilly Circus’. Ambient Screens and Transnational Public Spaces. Nikos, Papastergiadis (ed.), Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 81–94.

Debord, Guy. (2016). Society of the Spectacle. Detroit, MI: Black & Red.

Krajina, Zlatan. (2016). Negotiating the Mediated City: Everyday encounters with public screens. London: Routledge.

Lam, Lana. (2014). ‘50,000 CCTV cameras in Hong Kong’s skies causing “Intrusion” into private lives’. South China Morning Post, March 16 2014 https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/article/1449669/cctv-cameras-run-tens-thousands-across-hong-kong . Accessed 28 June 2021

Li, Sandy. (2016). ‘Sogo operator Lifestyle International wins Kai Tak site for HK$7.39b’. South China Morning Post, November 23 2016 https://www.scmp.com/property/hong-kong-china/article/2048683/sogo-owner-lifestyle-international-wins-kai-tak-site-hk739b . Accessed 22 January 2020

Mosco, Vincent. (2005). The Digital Sublime: Myth, power, and cyberspace. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nason, Emily M.; Fernandez, Joseph. (2018). SOGO: Leveraging digital technologies to enhance customer engagement and drive growth. Hong Kong: HKUST Business School.

Papastergiadis, Nikos; Barikin, Amelia; McQuire, Scott. (2016). ‘Conclusion: ambient screens’. Ambient Screens and Transnational Public Spaces. Papastergiadis, Nikos (ed.), Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 211–38.

Papastergiadis, Nikos; Barikin, Amelia; McQuire, Scott; Yue, Audrey. (2016). ‘Introduction: screen cultures and public spaces’. Ambient Screens and Transnational Public Spaces. Papastergiadis, Nikos (ed.), Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, pp. 3–28.

Scholte, Jan Aart. (2014). ‘Civil society and financial markets: What is not happening and why’. Citizens vs. How Civil Society Is Rethinking the Economy in a Time of Crises. Fioramonti, Lorenzo, Thümler, Ekkehard Ekkehard (eds.), London: Taylor & Francis, pp. 13–31.

Sito, Peggy. (2018). ‘Causeway Bay’s Russell Street Trumps 5th Avenue in New York as the world’s most expensive retail rental market’. South China Morning Post, November 14 2018 https://www.scmp.com/business/article/2173072/hong-kongs-causeway-bay-takes-over-new-yorks-5th-avenue-worlds-most . Accessed 22 January 2020

Tomlinson, Peta. (2019). ‘100 creatives, 10 years, 1 vision: how Hong Kong’s K11 Musea, part shopping mall, part museum, came to life’. South China Morning Post, December 2 2019 https://www.scmp.com/lifestyle/arts-culture/article/3039908/100-creatives-10-years-1-vision-how-hong-kongs-k11-musea . Accessed 28 June 2021