After the white-nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, on 11 August 2017, opinions are divided whether to remove or keep Confederate monuments. As someone born and raised in the Deep South, as a Jew, and as an art historian and educator, I too would like to weigh in. I have thought a lot about the subject since I needed to discuss the issue with my students in the City University of New York. I perceive the controversy as someone who, growing up in Atlanta, Georgia, experienced antisemitism and observed racism and Confederate pride.

The icons of the Confederacy were always a part of my childhood. In the Atlanta public schools and even at a Jewish summer camp in North Carolina, we sang without questions, the words of “Dixie”: Oh, I wish I was in the land of cotton,/ Old times there are not forgotten.” This song was a mark of belonging. Never mind that my ancestors had only arrived in the South as immigrants from Eastern Europe in the early twentieth century. They were grateful to flee oppression against the Jews and settle in Mississippi and Georgia, making their lives and raising their families in the Deep South in the heart of the Bible Belt. Coping with racism, antisemitism, and the threat of violence by the Ku Klux Klan was just part of their lives.

Growing up in Atlanta, the Old South and the Confederacy were never far away. I lived on Margaret Mitchell Drive and attended Margaret Mitchell Elementary School, proudly named after the bestselling author of Gone with the Wind, the 1936 novel set in Georgia during the Civil War and Reconstruction Era. Although we students escaped having any portraits of Confederate generals or President Jefferson Davis, the auditorium in our school did display a portrait of Mitchell and, from the 1939 movie, a huge portrait of Vivien Leigh as the Southern belle, Scarlett O’Hara.

I am not sure when I first heard about the Confederate cabinet officer Judah P. Benjamin (1811–1884), who became the first Jew to hold such high office in North America. By the time I entered high school, he was known to me, probably from reading about him and other Jews of accomplishment in Sunday School classes. These were held at Atlanta’s Ahavath Achim (Brotherly Love) synagogue, which was founded in 1886 by Jews of Eastern European descent, who felt uncomfortable in the established Reform synagogue, the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation (The Temple), whose members, mainly of Jews from Germany, practised more liberal doctrine. Yet neither Benjamin’s history as a slave owner nor the fact that he had not married a Jew, but a Catholic, would have made a Jewish hero out of him at the time of the Civil Rights struggle in Atlanta.

In public school, however, as in the Atlanta community at large, we were officially encouraged to take pride in a romanticized and nostalgic vision of the Old South. For example, when I won the school’s spelling bee, the prize was a trip with my teacher to see the twentieth-anniversary showing of Gone with the Wind, where it had premiered – the Loews Grand Theater, adorned with a columned facade that was supposed to recall Tara, the plantation of Scarlett’s family. Yet, for many, this movie is Hollywood’s glorification of slavery.

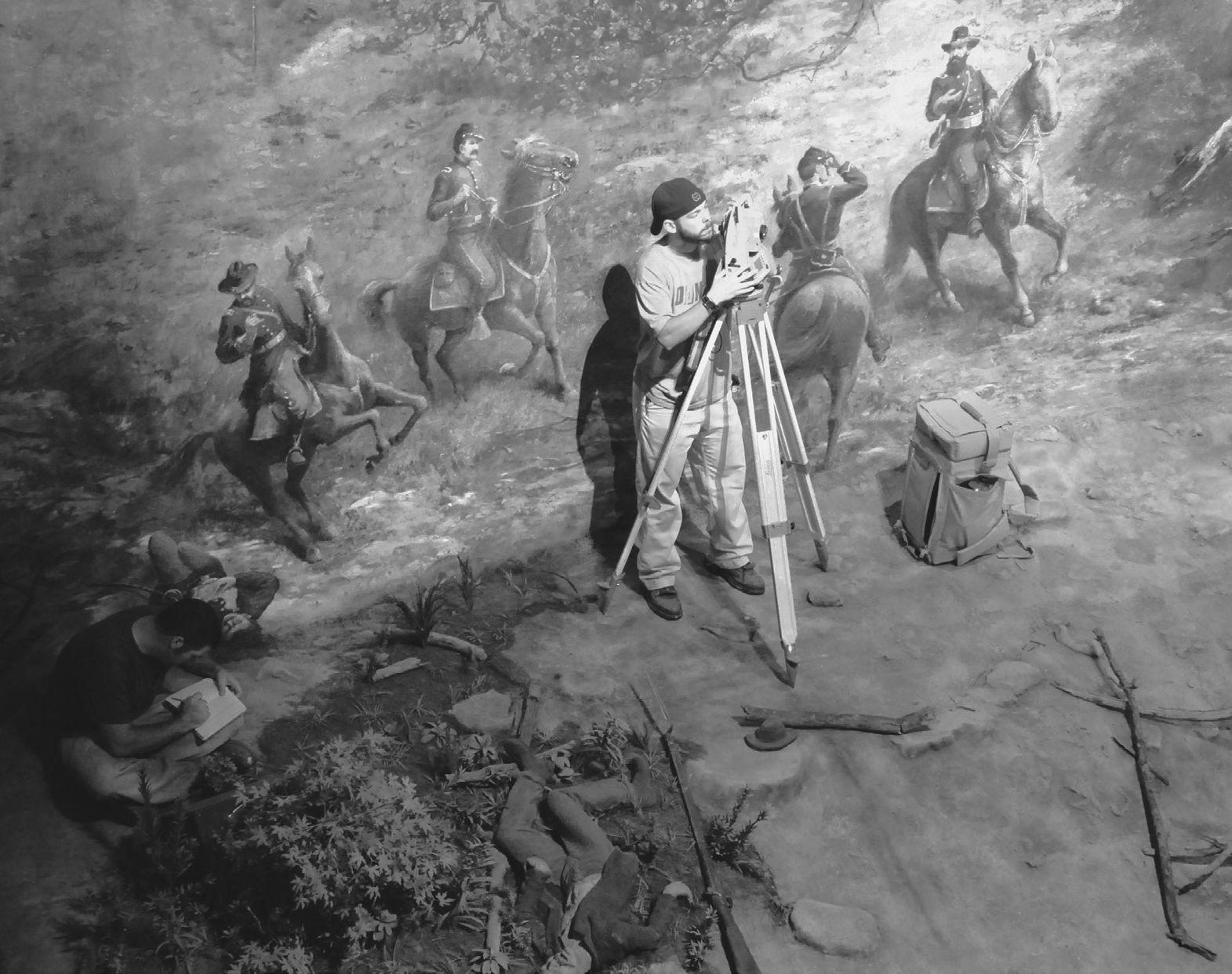

Despite General Sherman’s defeat and burning of the city, pride in the Civil War prevailed in Atlanta when I was growing up there in the early 1960s. The state flag (from 1956 until 2001) featured the stars and bars that the Confederate Army carried into battle. Our school took trips to the Atlanta Cyclorama, a huge panoramic painting from 1886, depicting the Battle of Atlanta. Later I learned with surprise that that it had been painted for the American Cyclorama Company by ten German artists working in Milwaukee. Three-dimensional figures were added by the WPA, during the New Deal, between 1934 and 1936, creating a kind of large-scale diorama. One viewed this assemblage from a turning platform in the centre of the long circular painting, while listening to a dramatic recorded narrative about the fierce fighting as Confederate defenders of Atlanta unsuccessfully counter-attacked the Union army on 22 July 1864. I learned early on that the symbol for Atlanta was the phoenix, the mythical bird that, like our city, rose from the ashes after Sherman’s attack.

Surveying the Battle of Atlanta cyclorama, 1886, with three-dimensional figures added 1934–36, after its move to the custom-built Lloyd and Mary Ann Whitaker Cyclorama Building, Atlanta History Center, to be reopened in autumn 2018. Courtesy of the the Kenan Research Center, Atlanta History Center

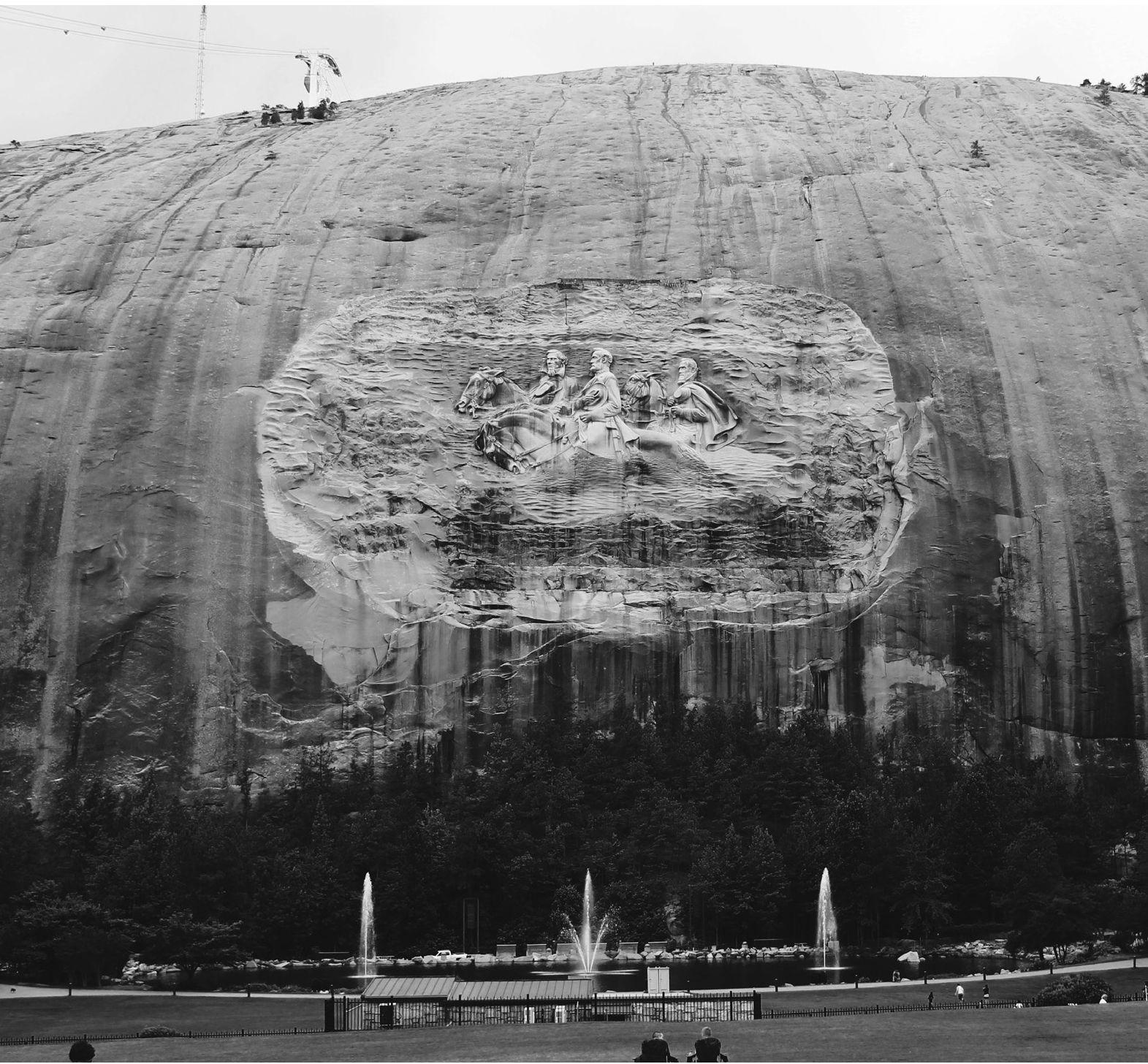

Thus, I grew up Jewish in Atlanta, in the shadow, so to speak, of the Confederacy. The monumental carving on the granite face of Stone Mountain, features Confederate “heroes” – Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, and Jefferson Davis – who literally loom larger than life. This carving is advertised as the largest bas-relief in the world. The State of Georgia purchased the mountain with the relief still unfinished in 1958, but it was “completed” from 1964 to 1972, supervised by the sculptor Walker Kirkland Hancock of Gloucester, Massachusetts. It is ironic that Hancock served as one of America’s “Monuments Men”, who rescued art treasures looted by the Nazis during the Second World War. Stone Mountain remains the one Confederate monument that you can hardly avoid seeing because of its huge size and location. It was well known during my childhood that the mountain was linked to the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) that menaced Blacks, Catholics, and Jews.

The 500-metre high granite outcrop with carvings of the Confederate generals Robert E. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and Jefferson Davis, Stone Mountain, Georgia, “completed” 1972. © Sarah Pascual, http://https://oursforever.wordpress.com/2013/07/18/stone-mountain-park

Stone Mountain, long after the federal government had suppressed the original KKK in the early 1870s, was in 1915 the site of the founding of the second Ku Klux Klan. This revival of the KKK has been linked to the Atlanta showing of D. W. Griffith’s film The Birth of a Nation in December 1915, and to the August 1915 lynching of Leo Frank, a Jewish man falsely accused of murdering a young girl, who worked in the pencil factory that he managed. Frank’s fate remained in the Jewish collective memory, striking so much fear in Jewish southerners that it is said to have shaped their behaviour for the next fifty years. That pattern changed only with the Civil Rights Movement and the arrival of many Jewish Freedom Riders from the North.

When I was a child in the late 1950s, the Klan was still holding rallies in downtown Atlanta. I have a traumatic memory of emerging from a Saturday morning matinee for children at the Rialto Theater downtown, only to see masked figures milling about in white sheets. I knew that this group was violent and that they did not like Jews. I now know that the KKK had drawn new strength from resistance to federal mandates for desegregation ordered by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. On top of Stone Mountain, the reorganized KKK staged a large rally in 1956, complete with a huge cross burning. These became annual events.

I was only ten years old on 12 October 1958 when I heard that The Temple, then prominently located on Peachtree Street, had been bombed and extensively damaged. It was not our synagogue, but some of my cousins’ families were members. Among the five suspects, only one was even tried. His first trial ended with a hung jury and his second with an acquittal. Among his legal defence team was James R. Venable, a white supremacist whose ancestors owned Stone Mountain. He later became the Imperial Wizard of the National Knights of the Ku Klux Klan. One of the jurors in favour of acquittal told reporters that “You can’t send a man to the penitentiary for life just because he’s a Jew-hater.”1 No one was ever convicted of the bombing. The Temple’s rabbi, Jacob Rothschild, had a high profile as an early supporter of civil rights and integration. He was known to be a friend of Martin Luther King Jr.

Detective W. K. Perry and a fireman surveying the Hebrew Benevolent Congregation (later known as simply The Temple) following its bombing, Atlanta, Georgia, 12 October 1958. Copyright Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Courtesy of Georgia State University. AJCNS1958-10-00h, Atlanta Journal-Constitution Photographic Archives. Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library

As a child, I feared that desegregation would lead to violence that would force our public schools to close. I had already seen images of closed schools in Little Rock, where Arkansas’s Governor Orville Faubus had ordered the closure of all four public high schools in an effort to prevent black and white students from attending the same schools. I was going into eighth grade when it was announced that my new high school would admit a token number of black students through a programme of “forced busing”. Although I did not mind integration, I implored my parents to send me to a private school so that I would not be prevented from finishing high school and be able to go to college. My father assured me that our public schools would not close and that he believed in public education.

He had taught me something about race. As a child, I had encountered at the Atlanta Airport public restrooms and water fountains marked either “White” or “Colored”. He told me that this was wrong, that all people were created equal, and that it would not matter if a black family lived in the house next to ours. He used to recite Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address. When I was about twelve years old, I saw that my father was reading The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, a thick 1960 book by William L. Shirer that chronicles Nazi Germany from Hitler’s birth in 1889 to the end of the war. This coincided with my father encouraging me to read both Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables and Gone with the Wind. Perhaps my father wanted me to read Hugo not just for its literary merit, but so that I would understand how poverty can degrade. But why, I wonder now, did my father want me to read Mitchell’s version of the Old South? Perhaps beyond the pleasure of best-selling fiction, he wanted to make sure that I understood the culture around me that named both my street and my elementary school. He was probably confident that I already had the ability to know right from wrong and that I would see through the novel’s rather benign view of slavery.

The Civil Rights Movement was then getting into high gear. A token number of black students attended my high school and, as my father predicted, it did not close. But racism continued to loom large. When we heard at school on 22 November 1963 the announcement that President Kennedy had been assassinated, our American history teacher had to remove Kennedy’s photograph from her classroom wall, which she had been displaying upside down. She was rumoured to belong to the John Birch Society, which we knew as a radical far-right group.

That same year, in that same school, my English teacher, Miss Mary Binns, suggested that I read James Baldwin’s somewhat autobiographical 1953 novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain. Recommending Baldwin, who was then known as a spokesperson for civil rights, was radical for that time and place. I began to read other books by Baldwin as well, who for me opened up a number of possibilities. Unquestioned assumptions about the South began to crumble.

An opportunity came in November 1964 to hear Martin Luther King, Jr. preach at his father’s Ebenezer Baptist Church. I cannot take credit for knowing about King’s appearance in Atlanta. My best friend’s sister was dating a college student from the North who attended Georgia Tech. He invited us to join him to go and hear King’s Sunday sermon and drove us there, to a black neighbourhood we did not know. We sat in the balcony – four white kids made welcome by the black congregation. I remember that I was moved by King’s message and by the call and response to his sermon.

After that, I wanted out of the South and all that it represented. I graduated from high school and went off to college in Boston at the age of seventeen. When my parents insisted that I come home to Atlanta the summer after my freshman year, I signed on to teach in an all-black school in a poor neighbourhood in Project Head Start, a programme for pre-schoolers in the second year of President Lyndon Johnson’s “War on Poverty”. The summer programme was intended to teach disadvantaged low-income children in a few weeks what they needed to know to start elementary school.

I was the only white teacher, but made to feel most welcome by the other teachers, students, and their families. Segregation was still so entrenched that these young children had only seen white people on television. At the end of the summer, I turned down the offer of a job teaching at the school in order to return to Boston and finish college. I put segregation, racism, and the colossal figures on horseback on Stone Mountain out of my mind, but the image of the Old South did not fade.

So, after the events of Charlottesville, I pondered how to relate all this to my students. First, they need to know that art images can become symbols with broad cultural implications. They need to learn to examine any artwork for its implicit political message. To do that they need to know the history of a monument, who put it there, who produced it, and why.

All public works have both detractors and supporters; they can damage or inspire. But what remains largely unspoken is how these symbols become an ingrained part of any culture. A populace can even become numbed into accepting them. Then at least some people no longer question the assumptions made by the presence of the work of art. In the case of the Jews in Atlanta, we can attribute their silence to the fallout of fear following the lynching of Leo Frank and continual intimidation by the Klan. Rather than admit and express their outrage, it seemed safer to overlook a certain level of injustice. Go with the flow. Blend in. Sing “Dixie”. This included accepting the imagery of the Confederacy on the state flag, in literature, and in public monuments. This, in fact, is what I think happened to me growing up.

On first hearing plans to remove statues of Confederate generals, my natural inclination as an art historian and curator was to argue that we should preserve monuments of history and learn from them. I imagined adding historical context in the form of a nearby wall of humane thinking, which would speak out against racial injustice and be designed by one of the excellent contemporary African-American artists who work with issues of race today.

Planning to discuss this topic with my students in my global survey of art history, I began to reflect on when past artworks have been destroyed and why. I quickly realized that it is important to remove these offensive statues from public places and to preserve them in some history museum that can contextualize them, addressing issues of racial injustice and its origins in slavery in the United States. Thus, we can still learn from these monuments without having them cause daily affront to the descendants of slaves, or encouraging others to accept this racist subtext of so-called “heritage” without questioning it. In fact, once we look into these monuments and realize when they were commissioned and what they represent, it is necessary to reject the desires of those clinging to fantasies of racial superiority in Jim Crow America. Today there are still those trying to impose their racist ideas on society. We do not want their sculptures in our parks and public squares.

Most of the statues of Confederate generals that still remain across the South lack either the rarity or the aesthetic distinction of the colossal fourth and fifth-century Buddhas at Bamiyan in Afghanistan, which were blasted out of existence by the Taliban in 2001. Instead, these contested Confederate equestrian figures and standing male soldiers are more like the state-sponsored statues of Stalin removed in Russia after the end of Communism. Rather than important works by individual artists, these Confederate statues were casts, mass-produced in the North and given only minor touches to distinguish them from statues of Union generals.

The recent illegal removal of one Confederate general in Durham, North Carolina, is reminiscent of the toppling of sculptures of Saddam Hussain, when the United States moved into Iraq in 2003. It turned out that this was a moment to celebrate the end of a tyrannical ruler although it did not turn out to be what George W. Bush pronounced: “Mission Accomplished.”

Removing monuments to the defeated Confederacy should not be viewed as erasing history, but as moving on to create a society that stands for the words in the second paragraph of the Declaration of Independence: “that all men are created equal”. Slavery has no place in this land, nor does its successor – the denial of rights to some according to the colour of their skin or place of national origin. But I want my students to think about this issue for themselves within a global context.

As I looked for images for my class lecture on the issue of whether to remove or not to remove an offending sculpture from a public place, I found Johannes Adam Simon Oertel’s 1859 painting, Sons of Liberty pulling down the statue of George III of the United Kingdom on Bowling Green, in New York City in 1776. This image recalling the start of the American Revolution was appealing enough that John C. McRae, an engraver and printer in New York, reproduced a popular version of it as an engraving that could be more widely distributed.Seeing agitators for independence decide to remove a statue of the king whom they viewed as tyrannical should remind us that the removal of such monuments signifying oppression is a part of American history from its inception. Likewise, the descendants of former slaves should not have to suffer the reminder of the inhumanity that their ancestors endured.

History makes clear that in most cases it is the voice of the victor that is given the place of honour in public squares. That did not happen in the post-Civil War American South. Now, removing public art commemorating the Confederacy is not simple, but it is necessary in most cases. The one instance that poses a more difficult dilemma is the monumental carving on Stone Mountain. I have heard a suggestion that figures representing Martin Luther King, Jr. and the former president and Georgia native, Jimmy Carter, should be added. But this would put the defeated Confederates on a level with King and Carter.

Asked about the issue of removing Confederate statues, Carter reflected:

That’s a hard one for me. My great-grandfather was at Gettysburg on the Southern side and his two brothers were with him in the Sumter artillery. One of them was wounded but none of them were killed. I never have looked on the carvings on Stone Mountain or the statues as being racist in their intent. But I can understand African-Americans’ aversion to them, and I sympathize with them. But I don’t have any objection to them being labeled with explanatory labels or that sort of thing.2

To address the thorny issue of the Stone Mountain carving, I recommend that some foundation or the state of Georgia fund an exploratory committee of leading artists, scholars, curators, and historians including African-Americans and Jews. This committee should come up with a proposal to contextualize this problematic monument with a museum on the site about the history of racial discrimination, antisemitism, and slavery in the South from the earliest days until today. Another, much more drastic, possibility would be to transform the mountain once again, changing the images altogether. But I think that the special instance of Stone Mountain, because of its size, placement, oppressive imagery, and its long role in the history of white nationalism, requires much more study before taking action.

© 2017, The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY) 4.0 http://https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Notes

- Claude Sitton, “Mistrial Called in Bombing Case”, New York Times, 11 Dec. 1958, 7. ⮭

- Jimmy Carter interviewed by Maureen Dowd, “Jimmy Carter Lusts for a Trump Posting”, New York Times, 21 Oct. 2017. Every effort has been made to trace copyright ownership and to obtain permission for reproduction of the images in this article. If you believe you are the copyright owner of an image in this article, and we have not requested your permission, please contact us. ⮭