TAG@UCL

The Theoretical Archaeology Group conference for 2019 was held at the UCL Institute of Education on 16–18 December. TAG is a venerable institution in British archaeology, having taken place annually since 1977. It has only been hosted once before in London, in 1986, when it was a rather smaller event and could be accommodated in the UCL union building (now Student Central), which fittingly provided the party venue for the 2019 conference. By contrast, TAG@UCL welcomed over 600 delegates and was one of the biggest TAG meetings of recent times. The overall theme of the event was ‘power, knowledge and the past’, placing an emphasis on the politics of archaeology, and the archaeology of power, which have been increasingly topical subjects in relation to world events of recent years. Across two-and-a-half days of scheduled activities, there were 51 sessions, as well as numerous walking tours, practical workshops and special museum access arrangements. The breadth of topics covered in the individual sessions was of course vast, but in keeping with the conference theme there were numerous discussions of political aspects of participation, representation and interpretation within the contemporary discipline of archaeology, wherever its practitioners work, as well as of different forms of power in past societies. The conference was kept running by a large team of student volunteers, and admirably supported by the conference staff team at the Institute of Education. Any enterprise of this nature is inherently collaborative, but TAG@UCL delivered on our aspiration to host an inclusive and dynamic event which was more than the sum of its parts, gathering archaeologists from all over the world to work together on our common challenges.

The Childe Lecture and the plenary session

Among the special events taking place around the conference, a couple of occasions provided the opportunity for larger audiences to gather and take part in broad discussion of the conference themes. The first of these, scheduled just before the conference proper, was Matthew Johnson’s Gordon Childe lecture, ‘On Writing the Past Backwards’, a fascinating engagement with the long-term social stratifications embedded in the English landscape (reported on landscape; see p.66). On the first full day of the conference itself, the Antiquity plenary session on Monday 16 December brought together a diverse group of panellists to discuss the question, ‘What is the Past Good for in the World of 2020?’. Liv Nilsson Stutz (Linnaeus University, Sweden), Arike Oke (Black Cultural Archives, London), Dominic Perring (Archaeology South-East/CAA, UCL) and Alfredo González-Ruibal (Incipit-CSIC, Spain) each spoke for a few minutes on their responses to this question, before a panel discussion and audience questions explored the diverse positive and negative impacts of interpretations of the past in today’s divided world. This followed the formal opening of the conference by Sue Hamilton as Director of the Institute; the Dean of the Social and Historical Sciences Faculty, Sasha Roseneil; and the chair of the TAG National Committee, Tim Darvill.

Beyond the sessions

Hosting a conference in central London has some disadvantages – until the UCL merger with the Institute of Education, lack of space was the major reason for the long interval between London TAGs – but it has many advantages too. One of these is of course the proximity to many other great institutions, and we were fortunate to be organising the conference just after a year-long programme of collaborative activities between UCL and the British Museum. Delegates to the conference were able to take advantage of special access to the Troy: Myth and reality exhibition at the BM during the event. Similarly, our own Petrie Museum gave delegates a dedicated viewing session, and one of the workshops took attendees behind the scenes in another UCL exhibition space, the Octagon Gallery. Walking tours led conference participants around the many points of interest in Bloomsbury and further afield in London, including aspects of the Roman city. Within the main conference venue, we also tried to diversify the programme by encouraging non-standard session formats, which included some lively debates, and providing a break-out room with archaeological board games and video games. This complemented the traditional exhibitors’ hall, which hosted a good selection of bookstalls and organisations. At the time of writing, in August 2020, with everything that has happened since the start of this year, it is a particularly fond recollection of TAG to think of all of the conversations with colleagues in that hall, where we also served coffee, and of how important the social aspects of a conference are. In concluding this report I have invited a handful of other reflections on the event, as only others can judge its success. On behalf of the conference committee I would like to thank everyone who made the organisation happen, and everyone who came, and hope that we can resume gatherings like TAG in the near future.

Reflections on TAG@UCL

‘My thoughts reflect not just changing TAG conferences, but the changing world with particular respect to #metoo and Black Lives Matter. They also reflect my changing perspective after nine years teaching at a university in the suburbs of Chicago. I thought TAG 2019 marked an historic shift. At any TAG, there are always some great papers and sessions, and some less great papers and sessions. What marked this TAG out was its greater diversity in terms of speakers and participants, and its commitment to inclusion and to social justice. Frankly, however well-intentioned I and other organisers and participants have been in the past, TAG has, historically, mostly been a bunch of white people talking to each other. Its avowedly radical and transformative aims have always been compromised by the whiteness of the discipline and by existing power structures. My generation has not done enough to confront these issues and has not worked hard enough to identify and dismantle existing inequities. There were signs at London TAG that times are changing for the better, though there is much to do.’ (Professor Matthew Johnson, Department of Anthropology, Northwestern University, USA)

‘Despite being in archaeology for 35 years, 2019 was the year of my first TAG. Not only my first TAG, but in at the deep end organising a session: talk about a baptism of fire! Our session (with Anne Teather) was “Powerful Artefacts in Time and Space” and, due to a huge number of session applicants, we shared our session with Professor Peter Wells, which was a lovely experience and brought greater depth to our range of papers’.

Beyond the papers it was a wonderful event: friendly, inclusive and open. I was able to catch up with many friends and colleagues I hadn’t seen for years, and all the conference helpers were visible, smiley and helpful – as one who organises conferences I fully realise how much hard work goes into making a conference run smoothly. Ten out of ten to the UCL team who did a great job making this TAG newbie feel welcome and wanted!’ (Dr Tessa Machling, Membership and Administrative Secretary, The Prehistoric Society)

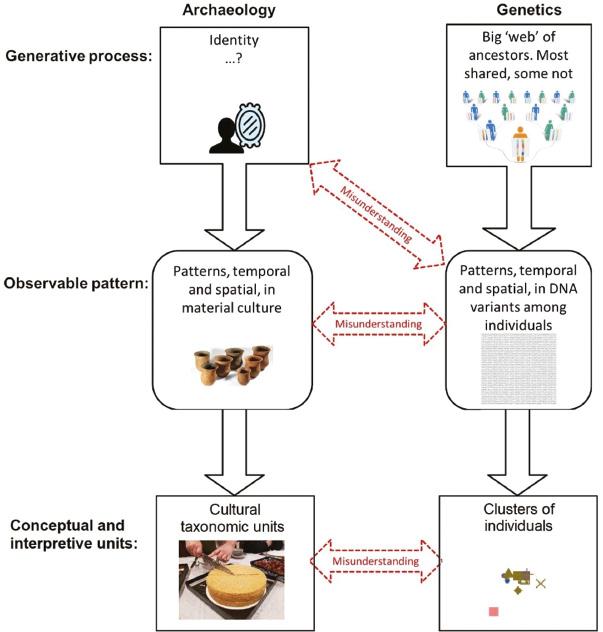

Reflections on the session ‘Archaeology, Ancestry and Human Genomics’

‘Reconciling archaeological data and the evidence of ancient DNA is arguably the most urgent theoretical challenge facing our discipline, or at least this is what prompted Brenna Hassett and David Wengrow to put out an open call for panel members, to discuss “Archaeology, Ancestry, and Human Genomics” at TAG 2019. The call was answered by a mix of geneticists (Pontus Skoglund, Selina Brace, Mark Thomas) brave enough to present their views in front of a large and vocal audience of archaeologists; archaeologists who have no such qualms (Rachel Pope, Kenneth Brophy, Susanne Hackenbeck, Natasha Reynolds, Martin Furholt, Alexandra Iron); and Thomas Booth, who seems to have ended up somewhere in between. After roughly four hours of sustained and often intense debate, driven as much by the audience as the panel, nobody could be left in any doubt that there are major theoretical and methodological issues to be faced which have barely begun to be resolved in our respective fields. To give something of a flavour, among the topics raised were the different meanings attached to terms such as “ancestry” and “migration” by geneticists, archaeologists and historians; implications of the term “admixture” as applied to human populations; the ethical challenges of obtaining and archiving human DNA from archaeological deposits; the role of archaeological context in shaping the interpretation of ancient DNA; the institutional frameworks of collaboration between archaeologists and geneticists, and our professional responsibilities in communicating joint findings to the public (including press releases, and some of the more politically disturbing outcomes that can follow, when these touch on issues of national identity and race). Perhaps the single most important conclusion reached was that the theoretical work of reconciling data from these two disciplines is still in its infancy, as expressed visually in a diagram (Figure 4) put together by Pontus Skoglund of the Francis Crick Institute, and subsequently modified by the prehistorian Natasha Reynolds, which we think nicely sums up the current state of the field.’ (Professor David Wengrow and Brenna Hassett, UCL Institute of Archaeology)