‘The advantages of the post on the other hand are these. Its holder would have the making not merely of the job, but to a large extent of the Institute. He or she will start from nothing and will build up something which ought to be pretty good. We need someone with an academic training and with imagination and a heap of commonsense’. 1

Introduction

Dame Kathleen Kenyon (1906–1978), one of the most influential women archaeologists of the 20th century, enjoyed a long and fruitful relationship with the University of London (later UCL) Institute of Archaeology, which she described as an ‘eccentric and utterly atypical institution’ (Kenyon 1970: 108). She was Secretary (1935–1948), Acting Director (1942–1946) and lecturer in Palestinian Archaeology, leaving only in 1961 to become Principal of St. Hugh’s College, Oxford. Kenyon’s life is well documented, with accounts by colleagues, friends and former students (Dever 2004; Moorey 1992; Parr 2004; Prag 1992) and a detailed, wide-ranging biography (Davis 2008). Kenyon was considered a brilliant field archaeologist, the ‘Mistress of Stratigraphy’ (Dever 2004: 528), but she was more than this: her wide-ranging career also included administration, recruiting students, lecturing, publishing, chairing committees, organising conferences, curating collections and even becoming a figure of media interest. As Acting Director of the Institute, she became the first woman to lead a major branch of a British university (Davis 2008: 89, Figure 1).

Using archives from the UCL Institute of Archaeology and Special Collections, this study seeks to move away from excavation-centred studies of Kenyon to shed light on her administrative career. Kenyon spent thirteen years as the Institute of Archaeology’s chief administrator, as well as serving as Secretary to the Council for British Archaeology (1944–1948) and volunteering for the Palestinian Exploration Fund (1935–1955). The study will also provide a gender-critical perspective of her career within the British archaeological community and in the process, reveal the vital work done by female administrators, who took advantage of expanding opportunities in the inter-war period to carve out professional spaces for themselves. Along with them, Kenyon faced significant challenges: discrimination, calculated interference and negative character judgements that remain embedded in discourses about her to this day.

Kenyon in Context: Histories of Women in Archaeology and Women in Inter-War History

Kenyon’s archaeological career needs to be examined within the wider contexts of archaeology and contemporary society. As earlier male concerns about female participation in excavations faded (Moorey 1992: 92), women gained increasing influence within the British archaeological community during the inter-war period. They infiltrated the Society of Antiquaries (Hawkes 1982: 125); local societies gave them a chance to develop as excavators, for example Elsie Clifford (1885–1976) and Maud Cunnington (1869–1951). Women also participated in excavations overseas, including Winifred Lamb (1894–1963), who led excavations in Greece (Champion 1998: 177–178).

Narratives about individual female excavators reflect contemporary attitudes that this was ‘above all, an age of excavation’ (Kenyon 1939: 251), but perpetuate male-centred histories of archaeology and perceptions that the only ‘true’ archaeology is excavation, a physically-demanding, male-cultured activity (Carr 2012: 9; Diaz Andreu and Stig Sorensen 1998; Hamilton 2007: 121–124). Finds processing work, museology and administration are seen as less prestigious, female-cultured activities and have received less historical attention (Hamilton 2007: 121; Carr 2012: 9). We need to move away from such ‘gendered’ discourses to understand fully the professionalisation of archaeology in the 20th century and women’s role within this process. Women excavated, but they also explored the wide options becoming available: Kenyon herself promoted women’s career opportunities: excavators, finds specialists, museologists, photographers, ‘draftsmen’ and finds repair staff (Kenyon 1943d) and in her fieldwork manual Beginning in Archaeology (Kenyon 1952: 162), emphasised: ‘he throughout the book should be read as he or she, for there are just as many openings for women as for men’.

Wider gender-critical contexts of female emancipation and recognition of shifting narratives about women’s professional and public status are also necessary (Colpus 2018: 201). Although there is much debate over women’s emancipation during the inter-war period, there is consensus that educated middle-class women, so-called ‘New Women’, experienced significant progress (Bingham 2004: Summerfield 1998; Colpus 2018): they were independent and self-sufficient; attended university; travelled and pursued professional careers (Summerfield 1998: 50–51). They could vote; they had the legal right to a career and divorce (Branson 1975: 209). There were changing cultures of sports and entertainment, new patterns of domestic life (McKibbin 1998: 370). They adopted mixed-sex activities and behaviours formerly regarded as distinctly masculine (Light 1991: 210). There were also significant shifts in attitudes towards female authority. 19th-century concepts of female authority were moral, focused on class and religion: ‘ladies’ fulfilling their maternal and marital missions, the kind of authority that allowed ‘archaeological wives’ such as Tessa Verney Wheeler (1883–1936) opportunity. These were slowly replaced by partial acceptance of women’s authority based on competency and rights and women began to forge professional identities (Colpus 2018: 201; Hinton 2002: 53; Woollacott 1998: 100).

But these new ideas, indeed these New Women, came under attack amidst fears they were rejecting marriage, domesticity and maternity and seeking to be independent of men (McKibbin 1998: 321–3). At a public level, England remained an almost exclusively single-sex society, with most important roles occupied by men. The proportion of women in the higher professions in 1950 was no higher than it was in 1914. Women worked for inferior pay and without private income, marriage was the only real way to escape poverty. They were still expected to give up their career on marriage (McKibbin 1998: 521). For many women, inroads into professions were temporary and personal and whilst progress was made, prejudice and discrimination continued (Summerfield 1998: 209).

Kenyon, the Wheelers and the Institute of Archaeology

In spite of her family connections and involvement in archaeology at the University of Oxford, Kenyon showed no interest in a career in the subject until after she left university in 1928 (Davis 2008: 26–28). It was excavating (1931–1935) in Samaria for the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and in the Roman town of Verulamium (St. Albans) with the Wheelers that established the interests that were to dominate her life: Romano-British and Palestinian archaeology (Davis 2008: 30–57; Moorey 1992: 96). R.E.M. Wheeler, Director of the London Museum, and his first wife Tessa Verney Wheeler were amongst the most influential of inter-war archaeologists (Hawkes 1982: 125). Both possessed archaeological talent coupled with enormous charm and charisma, which they used to great effect. The Wheelers were quick to recognise Kenyon’s talent. She became close to them, commenting: ‘I don’t think that many practising archaeologists came within the orbit of Rik and Tessa Wheeler earlier’ (Kenyon 1977: i).

It was through the Wheelers that Kenyon first became involved in the Institute of Archaeology. From as early as 1927, the Wheelers planned a London Institute or Board for the professional training of archaeologists, a dream shared by many of their generation. But funding and institutional backing were difficult to secure; it was not until 1932, when an Appeal Committee was established, that plans were set in motion (Evans 1987: 1, 6). In 1934 the Senate of the University of London agreed to include the proposed Institute as part of their federation (Evans 1987: 10), which united autonomous colleges and institutions in London (McKibbin 1998: 250–252). The University’s vision was to function as global centre of cultural influence and the ‘London external’ degree was considered an ‘imperial’ degree recognised as a way of advancement throughout the British Empire (McKibbin 1998: 252). Such a vision matched that of the Wheelers and their supporters, who wished to make the Institute a global centre for archaeological training, with an emphasis on the Middle East, particularly Palestine, a British Mandate where extensive archaeological fieldwork was being carried out (Kenyon 1936: 252). The focus on Palestinian archaeology was also prompted by the Institute’s primary source of funding, which came through the gift of eminent Egyptologist Flinders Petrie’s Palestinian collections to the Institute, accompanied by a donation of around £10,000 (later increased to £15,000) from his patron Mary Woodgate Wharrie (1847–1937) (Sparks and Ucko 2007: 13).

Kenyon always paid tribute to Wheeler as her mentor, her ‘constant inspiration towards improved methods’ (Kenyon 1952: 7) and their names are irrevocably linked in the Wheeler-Kenyon excavation method,2 but their relationship was based as much on their power-sharing relationship at the Institute as excavation. Their friendship was often tested and they could be critical of each other (Carr 2012: 154–155; Kenyon 1977: ii), but letters attest to the enduring affection shared by these two forceful people (Wheeler 1935a, 1935b, 1935c, 1970, 1973). Kenyon defended Wheeler against his critics (Kenyon 1977: ii). She also overlooked his womanising and remained publicly neutral over his complicated marital history. When questioned about Wheeler’s recent marriage to Mavis du Vere Cole (1908–1970) by an acquaintance, W. E. F. Macmillan, Kenyon glossed over the scandal surrounding the couple’s tumultuous relationship (Hawkes 1982: 181–190), stating only that they had ‘known each other for some years’ (Kenyon 1939c).

Kenyon’s relationship with Verney Wheeler is less well-documented, but the two women were close. Although Kenyon was to claim that she owed Wheeler ‘all my training in field archaeology’ (Kenyon 1952: 7), she also paid tribute to Verney Wheeler for training in dig management and field technique, notably detailed control of stratigraphy and pottery recording (Moorey 1992: 96; Carr 2012: 17, 182). The two women also shared a particular construct of female participation in archaeology: a strong commitment to training female students (Carr 2012: 182; Hamilton 2007: 138; Kenyon 1952) and the active promotion of female colleagues to professional roles, which may suggest a conscious continuity or community of female practice. Verney Wheeler, for example, involved Kenyon in the Institute (Davis 2008: 66); Kenyon promoted Joan du Plat Taylor (1906–1983), another Wheeler protégé, first as her assistant in the excavations at Leicester and then as Librarian at the Institute (Davis 2008: 79).

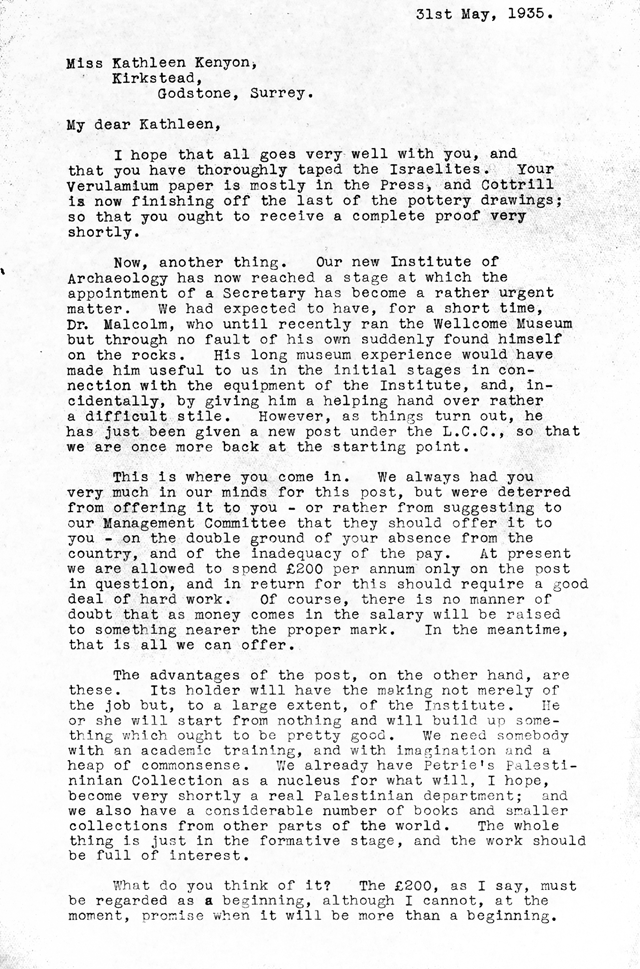

In January 1934, Kenyon gave ‘offers of help in respect of Palestinian Archaeology’, teaching and curating,3 to the new Institute. When this plan fell through, Wheeler decided to offer Kenyon the position of Secretary, writing to the Chair of the Institute Management Committee: ‘I propose to suggest Kathleen Kenyon for the job. She is a level-headed person, with useful experience both in this country and in Palestine’ (Hawkes 1982: 132). Wheeler also knew that she would not be dependent financially on the impecunious Institute, as she had a private income (Moorey 1992: 98). On 31st May 1935, he wrote to Kenyon (in Samaria) that the original plan was to offer the position to ‘Dr Malcolm who until recently ran the Wellcome Museum’. However, Malcolm now had another job, so they were offering it to Kenyon. The job would be hard work but its holder ‘would have the making not merely of the job, but to a large extent of the Institute’ (Wheeler 1935a; Figure 2).

Kenyon (1935) wrote from Samaria: ‘it ought to be frightfully interesting, but I doubt if I have much qualification for it’. In her forthright way, she outlined her difficulties: she would not be back in England until August and she needed to complete her contributions to the forthcoming Samaria excavation report. If Wheeler could wait until September, ‘I will accept like a shot’. She was, however, unlikely to stay for long: ‘it is the excavating part of archaeology that I really enjoy and I don’t suppose I should have much time for that’. Wheeler was determined that Kenyon would take the role. On 8th July 1935, he wrote with a formal offer from the Management Committee. They recognised that the post was poorly paid, with an annual salary of only £200 a year, and ‘is likely to be an arduous one’, but in return, they were happy to make provision for up to three months’ fieldwork each year (Wheeler 1935c), which was to prove vital; other female archaeologists, notably Margaret Murray (1863–1963), would find it difficult to escape their administrative responsibilities to excavate (Sparks 2013: 3).

New challenges: the Death of Tessa Verney Wheeler

Kenyon’s post began on 1st October 1935 (Wheeler 1935d) and work began sorting out the Institute’s new premises, the dilapidated St John’s Lodge in Regent’s Park, which Verney Wheeler had secured for a nominal rent (Carr 2012: 150). Kenyon and Verney Wheeler parcelled up tasks between them, with Kenyon taking on the Institute’s accounts and financial responsibilities from March 1936 (Perowne 1936a, 1936b). A superb example of their teamwork survives; Wheeler asks Kenyon to meet ‘Tess, a motor-van and a patrol of workmen’ to pick up exhibitions cases and boxes from University College. Tess would fill her in on the details (Wheeler 1936). Kenyon was to reminisce (1977: i): ‘Tess was a wonderful colleague’.

Initial arrangements came to an abrupt end with the death of Verney Wheeler on 15th April 1936 (Hawkes 1982: 137–138). Letters reveal the shock and resulting disarray, for she had been the practical organising force behind the Institute (Kenyon 1936a; 1936b). In a hitherto unknown letter from the Institute Library Archive, Kenyon wrote to Charles Peers (1868–1952), Chairman of the Institute’s Management Committee (1936b): ‘Mrs Wheeler’s death is a most terrible shock, and it is impossible to imagine how we shall manage without her’. Wheeler was to write that Kenyon ‘stepped into the breach with a generous devotion that is beyond gratitude’ (Wheeler 1955: 90), but this should not obscure the challenge she faced, for the new Institute had limited funds and minimal staff (Hawkes 1982: 138). At first Kenyon was tentative; she wrote to the Secretary of the Senate of the University that she can manage financial estimates for the Institute with some difficulty, but does not want to submit them until Wheeler has checked them (Kenyon 1936a). Nevertheless, she soon gained confidence, making decisions, for example, about the location of the drains and men’s cloakroom (Kenyon 1936c; Peers 1936a). By October 1936, all was ready. Kenyon wrote (1936c): ‘I am looking forward to a hectic and dirty time getting everything in order’.

In April 1937, the Earl of Athlone, the Chancellor of the University, officially opened the Institute (Hawkes 1982: 141). The Chancellor described Kenyon as ‘an admirable secretary’ (Anon 1937: 10), but her role was downplayed, for the Management Committee had decided to use the Institute to memorialise Verney Wheeler (Peers 1936b: 328). Wheeler wrote (1955: 90): ‘she would not mind my saying that Tessa would have been proud of her’, casting the relationship between the two women as teacher/mentor and student. In reality it was more complex and transitional professionally: friends, but also paid employee and unpaid archaeological wife. Kenyon belonged to a class and generation of women who valued self-control and heroic disavowal. Exhibition of feelings showed bad taste (Light 1991: 12, 162). She never gave her own version of this difficult transition, but demonstrated her loyalty and affection by taking on responsibility for co-ordinating a memorial to Verney Wheeler following a public appeal for funds by the Society of Antiquaries (Western Gazette 1936: 16).

Kenyon as Secretary: Alliances and Responsibilities

‘It was a happiness, then, to stroll into the Institute (as indeed it is now)! K.K. as she is affectionately called, would come into the ‘tea room’ from the office or lecture room, talk to old stagers about her problems – cases for the collections, additions to the library, ways of raising funds, suitable lecturers for the courses; then she would interview interested youngsters, taking cups of tea and buns in the intervals’. (Fox 1949: 66)

Kenyon’s job as Secretary was arduous, involving many tasks, which she undertook with the energy and enthusiasm for which she was famous all her life (Prag 1992: 113). A letter written from her Leicester excavations (Kenyon 1938d) suggests her responsibilities frequently overlapped; she was ‘up to her neck in Leicester mud’, but still answering Institute correspondence, negotiating with R.G. Collingwood (1889–1943) about book donations and discussing her archaeological discoveries with him.

Kenyon was responsible for recruiting and advising potential students (Fox 1949: 66: Kenyon 1952: 7). She lectured them on field archaeology course and on ‘excavation methods and organization in the Near East’ and gave public lectures (Anon 1938b: 16). She liaised with archaeological societies and arranged work for the Institute’s Repair Department, negotiating with the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle to exchange publications for the repair of two beakers (Kenyon 1938b). Although the Institute had a librarian, Lieutenant-Colonel Browne (1881–1963) (Anon 1938a: 4), he was only part-time and Kenyon did much of the library work. She organised exchanges (Dallas 1938a, 1938b) and begged donations, even collecting books from the Duke of St. Albans club (Kenyon 1938c).

Kenyon was also responsible for administering the Institute’s public-facing ventures, including exhibitions (Thornley 1938). She gave tours to prospective financial supporters (Kenyon 1939b) and promoted the Institute, writing to H. Mattingly (1884–1964) of the British Museum, an important contact (Kenyon 1938a): ‘I’m so glad you liked our lecture room’. She arranged for circulars of the Institute’s activities to be displayed at the Society of Antiquaries (Kenyon 1937a).

Kenyon was also responsible for the Institute’s museum collections, particularly the Petrie Palestinian collections, which she dated and arranged, making them accessible to students for research (Sparks 2007: 15). In 1937, attempts were made to raise funds for a lecture-curatorship in Palestinian Archaeology through a public appeal, emphasising the necessity for archaeological expertise in this field and the importance of the Institute’s collections (Sparks 2013). The position was intended for Kenyon, but insufficient funds were raised; there was no lecturer in Palestinian archaeology until 1948.

Kenyon has been described by those who knew her as ‘forceful’, ‘brusque’ and authoritarian (Davis 2008: 12; Parr 2004; Prag 1992). But surviving letters reveal that as Secretary, she could be diplomatic and patient. Petrie was demanding and suspicious over the care of his collections, but Kenyon gained his trust (Sparks and Ucko 2007: 13–15). The often imperious Peers came to respect her, writing (1949: 65): ‘her clear and orderly mind was of greatest value to all of us: but most of all to the Chairman who was thereby exempt, as far as that was possible, from the anxieties of his post’. She also dealt with the pedantic Academic Registrar of the University of London, S. J. Worsley (1895–1974); he complained (1936) that her explanation in an agenda of the constitution of the Committee of Management of the University was wrong. He writes: ‘let me explain’ and ends the letter: ‘I am sure you will not mind my pointing this out to you’.

Kenyon came to wield considerable power in the Institute as its chief administrator and second in command. Wheeler saw it as their shared vision, a partnership. Discussing concerns over the Petrie Palestinian Collection, he wrote (1970): ‘our whole idea – yours and mine – was to make the Institute a Research institution’. Wheeler and Verney Wheeler had employed a mother/father approach to leadership, balancing Verney Wheeler’s practicality and nurturing with Wheeler’s discipline and drive (Carr 2012: 251; Hawkes 1982: 119). Kenyon similarly did much of the day-to-day organising and nurturing, but she and Wheeler had a more consultative relationship. Wheeler gave her instructions and made suggestions: for example, she writes to Thornley (1938) to thank her for a donation as the ‘Director desires’; he passed on letters to her to answer (Kenyon 1940a). He in turn accepted her advice; she wrote to Harold Mattingly (1884–1964) regarding the Royal Numismatic Society Library (Kenyon 1937b): ‘I have consulted with Dr Wheeler about housing your library. He agrees with me that we should be very glad indeed to do so’. Kenyon also did what she felt was in the best interests of the Institute: for example she conspired to keep a ‘windfall’ of money in a long-forgotten bank account from Wheeler (1939a): ‘if Dr Wheeler were reminded about it, he might have different ideas about it!’ Wheeler in turn used Margot Eates (1889–1970), the Institute’s assistant secretary and his protégé from the London Museum (Hawkes 1982: 226) to keep up with Kenyon’s activities on the sly; they exchanged correspondence while he was in India about Kenyon and the Institute (Eates 1944). Unlike Verney Wheeler, who played a secondary role to Wheeler (Carr 2012: 18); Kenyon forged her own career and role within the Institute. This independence is an indication not only of Kenyon’s personality, but also of the new professionalism emerging in archaeological organisations.

The Institute was not without problems. It was desperately short of funds pre-war (Evans 1987: 16–17) and by 1943 it was in serious financial difficulties.4 Verney Wheeler and the Appeals Committee had raised start-up funds for the Institute (Carr 2012: 148–149) and it had a capital grant for maintenance from the University of London, but no annual grant and no annual income (Kenyon 1938a). Kenyon, along with the Institute’s solicitor E.S.M. Perowne (1864–1947) was responsible for the Institute’s accounts and they attempted to manage the inconsistent flow of income. There are few signs of sustained fund-raising, particularly the sophisticated ventures employed elsewhere, notably by the British School at Jerusalem (Sparks 2013). The Institute did use subscriptions, public lectures and exhibitions and tried to cultivate wealthy donors; in 1937, Kenyon wrote gleefully to Perowne (1937d): ‘I think we must give another sherry party. This one was certainly a good investment’; a donor had given them a cheque for £2500. But these attempts were only sporadic and Wheeler saw money from the University of London as the solution to the Institute’s financial problems (Kenyon 1938a). Kenyon was as ‘a tireless worker; by nature a creative organiser’ (Fox 1949: 66), but she took on many commitments and was reluctant to delegate (Parr 2004). This reluctance and her heavy workload may have prevented her raising funds as effectively as Verney Wheeler, but she may also have lacked Verney Wheeler’s financial acumen, talent for fund-raising and philanthropic connections (Figure 3).

New Women in Archaeological Administration during the early 20th century: Kenyon and Colleagues

During the inter-war period, administration became increasingly viewed as ‘women’s work’: by 1931, nearly half the clerical labour force was female, with the advantage that they could be paid at a much lower rate (Branson 1975: 211). Women archaeologists were more easily accepted in roles that were considered feminine (Diaz-Andreu and Stig Sorensen 1998: 15–16) and they increasingly appropriated administration. They got little recognition for their ‘invisible services’, much of it unpaid legwork, but their talents and enthusiasm began to professionalise archaeological administration. They shared resources, managed complex networks of information and acted as keepers of ‘institutional’ memory with gossip, advice and opinions. Archaeological organisations between the wars were surprisingly innovative, offering women opportunities to exercise leadership and to educate and entertain themselves; such activities were vital, overturning traditional masculine discourses of feminine incapacity (Bingham 2004; Hinton 2002: 94). Some gained real power and influence: Kenyon for example, was the only female member of the Management Committee (Anon 1938a: 10), although in general their status was regarded as subordinate.

Many of Kenyon’s colleagues were confident ‘New Women’, relishing the opportunities of inter-war Britain. Some were scholars in their own right. Isobel Thornley (1890–1941), Secretary of the British Archaeological Association, for example, was a distinguished medievalist. Both together and individually, the women found ways to subvert their subordinate positions and disprove contemporary claims that ‘women cannot work together’ and should not be placed in positions of authority (Summerfield 1998: 166). Vera Dallas (1893–1972), Assistant Secretary to the Royal Archaeological Institute, independent, caustic and astute, wrote brisk letters to Kenyon revealing cheerfully disrespectful ‘management’ of her male colleagues: she has arranged for the Council of the Royal Archaeological Institute to be given their tea early, otherwise they ‘will never get down to it’ (Dallas 1938a). Her knowledge of the British archaeological world was unparalleled; at the end of the war, Dallas (1945) gave Kenyon a detailed overview of the current state of local societies.

In spite of their growing importance, however, female administrators’ power remained transient and personal, nor was their appropriation of archaeological administration as an active ‘female’ space secure; Kenyon’s successors as Secretary to the Institute were both men: Ian Cornwall (1909–1994) and Edward Pydokke (1909–1976) (Evans 1987). Today, female administrators like Dallas and Thornley are forgotten and it is female administrators who also excavated, such as Kenyon, Verney Wheeler and Du Plat Taylor, who are remembered, demonstrating the dangers of preferring certain values in archaeology and erasing others that appear less heroic (Stig Sorensen 1998: 35). Their work may not have been glamorous, but administrators ‘normalised’ female decision-making in archaeological organizations and empowered women as ‘active citizens’ in archaeological practice.

Kenyon faced many of the unresolved tensions that women of her generation experienced. She was a New Woman: she loved gin; she smoked and played sports (Davis 2008: 24). She owned her own car. She had education, connections and a private income (Dever 2004: 526; Moorey 1992: 97). She pursued a career. She never married and her behaviour was almost ‘masculine in its manner’ (Davis 2008: 35, 71–72, 83). Kenyon denied that she faced any prejudice, stating: ‘You don’t consider whether you are a man or a woman. You are just an archaeologist’ (Davis 2008: 74). However, we should not take her words at face value. Contemporary social authority for women derived as much from the position of male relatives as their own experience and actions (Hinton 2002: 25). Frederic Kenyon’s (1863–1952) prestige and reputation within the British archaeological community unquestionably aided Kenyon’s career, but although she was being described as Britain’s ‘foremost woman archaeologist’ as early as 1944 (Market Harborough Advertiser and Midland Mail 1944: 1), she found it difficult to escape his shadow. Newspapers first became interested in Kenyon while she was at Oxford, because she was Frederic Kenyon’s daughter and, because as the first female President of the Oxford University Archaeological Society, she was articulating a modern femininity that played into the complex relationship between the media and gender identities (Bingham 2004: 233; Daily Mail Atlantic Edition 1927: 3). The media maintained interest in her as a pioneering female archaeologist and ‘a woman in charge’ for decades: ‘a woman is leading the latest efforts to lay bare more of the most important cities of Roman Britain’ (Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail 1936: 2). She is ‘Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries, Secretary of the Institute’, but qualifying statements always refer to her father: the ‘daughter of Sir Frederic Kenyon, former Director of the British Museum’ (Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail 1936: 2). For all her talents, even Kenyon could not avoid contemporary value judgements about women.

Kenyon as Acting Director: securing the Institute’s future and planning post-war British archaeology

The outbreak of World War II in 1939 brought significant changes. By February 1940, Wheeler was ‘away soldiering’ and passing all business to Kenyon (Kenyon 1940a), but it was only in April 1942, at the urging of the Institute Management Committee that she was appointed as Acting Director with the agreement of the University of London (Davis 2008: 89); she also still remained Secretary (Surrey Mirror 1945: 3). Like many women in Britain, the war gave Kenyon opportunities for authority and leadership, which she used to great effect for the Institute and British archaeology generally. But this authority was contingent and temporary and she was expected to relinquish the job after the war to a man (Kenyon 1944; Worsley 1944a); Kenyon relinquished it in 1946, when the Institute’s new Director, Vere Gordon Childe (1892–1957) arrived (Anon 1947: 11).

Although the Institute took no students during the war, it remained open, supporting the cultural Home Front in the form of exhibitions and lectures (Anon 1947: 8; Morgan and Evans 1993: 86). Kenyon juggled these responsibilities with full-time, paid work for the British Red Cross, in March 1942, becoming national Director of Youth for the Red Cross (Davis 2008: 85–88). In this role, Kenyon worked with the military, senior charity figures and government officials and travelled widely, addressing rallies and meetings in Lincolnshire, Nottingham and Coventry (Coventry Standard 1943: 6; Lincolnshire Echo 1944: 3; Nottingham Journal 1942: 2). She worked long hours, sometimes 18 hour days (Davis 2008: 114), and surviving letters reveal the intense strain she was under (Davis 2008: 86–87). She apologised to correspondents because she was missing lectures and could not find time to collect book donations (Kenyon 1940b). She was ‘hectically busy’ and absent from the Institute during the day (Kenyon 1942).

It is testament to her powers of organisation and hard work that as Acting Director Kenyon both assisted in securing the Institute’s financial future and making it a centre for planning post-war British archaeology. From 1943–1944, Kenyon organised two conferences at the Institute, the ‘Conference on the Future of Archaeology’ (August 1943) and ‘Problems and Prospects of European Archaeology’ (September 1944), which provided venues for archaeologists to plan for international post-war reconstruction. The conferences have been examined in detail (Evans 2008; Moshenska 2013), but less attention has been paid Kenyon’s initiative in setting them up, or her administrative talents and connections in bringing them to fruition. Stout (2008: 41–48) has interpreted the 1943 conference within the context of Christopher Hawkes’ (1905–1992) ambitions for British Archaeology. The conference provided disciplinary support to the Society of Antiquaries in establishing the Council for British Archaeology (CBA) (Clapham 1944: 91), but it was Kenyon who convened the planning committee in March 1943 and those involved were her personal allies, including her father and several women archaeologists: Joan Du Plat Taylor, Veronica Seton-Williams (1910–1992), Olga Tufnell (1905–1985) and Margerie Venables Taylor (1881–1963), the first female Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries. Kenyon persuaded the Institute’s Management Committee to back the conferences, in spite of concerns from Sidney Smith (1889–1979) and Stephen Glanville (1900–1956), Edwards Professor of Egyptology at UCL about the timing and absence of many archaeologists (Kenyon 1943a, 1943b).

The conferences reflect Kenyon’s personal ambitions for the future of archaeology and the Institute’s role within it, her alliance with innovators within the archaeological community and her commitment to state control and centralised authority for British archaeology (Clapham 1943: 91; Stout 2008: 43). They also reflect her wider beliefs, shared by many in the UK, that Britain should emerge from the war transformed into a more egalitarian society (Rose 2003: 62–63) and her experience in international post-war planning, gained through the British Red Cross (Nottingham Journal 1943: 4). She invited both the archaeological community and relevant government bodies to the conferences, including the Foreign Secretary and the Secretary of State for the Colonies (Kenyon 1943c), demonstrating the scope of her ambition. She stated: ‘Archaeology must play its part in any post-war extension of cultural and educational activities, both in this country, and in relations with Foreign powers, Mandated Territories, the Dominions and the Colonial Empire.’ Fox claimed (1949: 67) that she was merely Wheeler’s factotum: ‘she knew Wheeler’s intention that Institute should be a powerhouse of modern Archaeology, a centre for its development as a Science’, but this is to deny Kenyon her role; Wheeler was abroad and not involved.

Given the absence of many archaeologists on war-time service, the conferences yielded few concrete plans and actions (Moshenska 2013). One important initiative, however, was the establishment of the Council for British Archaeology (CBA) in March 1944 to promote all aspects of British archaeology while assuring proper excavation, public education and the preservation of historic sites. Kenyon became the first Secretary (Davis 2008: 93). Problems soon emerged between the CBA and the Office of the Ministry of Works, rooted in anxieties about state funding and public involvement in post-war archaeology, which exhibited itself in hostility towards the Council’s female members, which included Aileen Fox (1907–2005), Jacquetta Hawkes and Margot Eates. Bryan O’Neil (1905–1954), Chief Inspector of Ancient Monuments in England, under pressure from both sides, complained of ‘Miss Eates and the other ladies (Miss Kenyon, etc.) who are nosing about ostensibly on behalf of the Council for British Archaeology but without the body’s authority’ (Morris 2007: 348) and singled out Kenyon, an influential advocate of state funding. He accused her of being ‘tactless’, misrepresenting the CBA’s wishes, indulging in ‘unwise or at least careless publicity’ and most remarkably, as ‘lacking experience’. He even claimed she had been ‘reprimanded’ for her behaviour (Morris 2007: 346). How far these criticisms were justified is difficult to establish. The women may have been doing their job, or acting independently, but they served as convenient scapegoats; there was male hostility towards so-called ‘petticoat government’ throughout the war (Hinton 2002: 91).

Kenyon also experienced similar hostility towards female authority during the post-war expansion of the Institute into the University of London’s acknowledged and funded focus for Archaeology. Conventional accounts of the transition suggest a smooth process from autumn 1943, involving a sub-committee including Kenyon, Wheeler, Glanville and Fox (Evans 1987: 15–16). But, a letter from Margot Eates to Wheeler suggests a more fraught process, involving uncertainty over funding and changes from original plans regarding teaching and academic content (Eates 1944). Eates claimed that Kenyon had been obstructive during the process, ‘altogether rather difficult and not very tactful’, and that there were tensions between Kenyon and Glanville, the new Chair (since 1944) of the Management Committee, because she ‘has such a passion for having her own way’. The letter could be dismissed as Eates’ personal enmity, but apparent corroboration comes from Hawkes (1982: 226), who states that Glanville, abetted by Eates, facilitated the transition and not Kenyon.

Kenyon was strong-willed and could be jealous of her own authority (Davis 2008: 114) as Eates’ letter implies. But letters in the UCL archives also reveal that she faced gender discrimination from male colleagues over this issue. The Academic Registrar of the University of London, Worsley, returned from military service in September 1944 and began preparations for recruiting students. He expressed disquiet that ‘apart from Miss Kenyon, there is nobody at all at the Institute’ and students could not be registered (Kenyon 1944). Disregarding Kenyon completely, he demanded that the Institute Management Committee immediately appoint a full-time Honorary Director. In October 1944, he again by-passed Kenyon, agreeing decisions relating to the Institute about teaching rooms direct with Glanville and then relaying them to Kenyon (Worsley 1944b). The same month, the Management Committee agreed that a full-time Director needed to be appointed at the ‘earliest opportunity’: they proposed and the University approved, the appointment of Gordon Childe. Ironically, it was Kenyon, as Institute Secretary, who wrote the letter (Kenyon 1944): she had been effectively stripped of her power by male colleagues, including her own Management Committee, replaced, but still expected to remain in position and reopen the Institute. She received no formal thanks, nor recognition, for her war-time efforts until 1948 (Fox 1949: 7).

Dyhouse (1995: 153) has noted that women in academia were often cautious of admitting to discrimination and if encountered, it was often attributed to personal deficiencies, which chimes with Eates’ hostile labelling of Kenyon as tactless and self-willed. Kenyon did not comment on these events, although Eates’ letters hint at her frustration and tellingly, she was to later state that she believed that men were accepting of women as scholars, but not in positions of power (1970: 116):

‘I am not so sure that there would be complete fair play and lack of prejudice in supporting a woman to an important administrative post, such as the headship of an important scientific department. I would not say that supreme merit would not be recognized, but everything else being equal, I am sure that the balance would be tipped in favour of a man’.

Post-War: Lecturer in Palestinian Archaeology in a Changed Institute

Kenyon returned to her role as Secretary in 1946. She remained the Institute’s chief administrator, but her power rapidly diminished under the new regime. She appears to have had a good relationship with Childe (Kenyon 1952: 7), but they never developed a power-sharing partnership of the kind she had enjoyed with Wheeler, in part because the increasing involvement of the University of London and its personnel in the Institute’s affairs diversified authority in the Institute. By 1947, she was no longer a member of the Management Committee, which was now entirely male and heavily dominated by leading figures from the University (Anon 1948: 8). A University memorandum on staffing in 1946 describes her role: ‘administrative work. In charge of Palestinian and Roman collections’.

Kenyon remained busy, juggling administrative, teaching and excavating responsibilities, but her interests were increasingly focused away from the Institute at this time: she began excavating in war-damaged Southwark and undertook many administrative responsibilities for the CBA, sitting on panels representing Romano-British, Neolithic, Bronze Age and Iron Age archaeology, producing advisory pamphlets and summaries. She corresponded with local societies, helped them arrange excavations and set up student exchanges (Davis 2008: 93–95). A newspaper interview at this time reports that she has ‘no other hobbies. Archaeology is a full time job’ and places her administrative duties at the Institute firmly behind her digging responsibilities (Dundee Evening Telegraph 1947: 2). She resigned from the CBA in 1948 (Davis 2008: 94), perhaps in part because she had a new focus and a new role at the Institute, one which involved a complete break with her previous administrative career.

In 1948, funds became available to appoint Kenyon lecturer in Palestinian Archaeology, a position intended originally for her in 1937. The university also conferred on her the status of ‘Recognised Teacher’ (Davis 2008: 95). Prag (1992: 120–122) considered these developments as surprising, for although Kenyon was a superb lecturer, her fieldwork had been largely in Britain. But this discounts Kenyon’s long experience as curator of the Petrie Palestinian collections and her expertise in fieldwork, dig management and student training; more British archaeologists worked in Palestine than in any other area outside Britain and training was a priority (Davis 2008: 96). Kenyon’s focus moved away from administration towards excavation and academia, the traditional ‘male-cultured activities’ for which she is now remembered, although she was to later claim: ‘I am not in the least a dyed-in-the-wool woman academic’ (Kenyon 1970: 107). Kenyon continued to excavate in the UK and North Africa until 1952 when she re-established the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem and embarked on what are conventionally considered the greatest achievements of her career, the excavations of Jericho (1952–1958) and Jerusalem (1961–1967) (Davis 2008: 95–100). The media followed her discoveries with excitement: as ‘Miss Kenyon’ or sometimes ‘Dr Kenyon’, director of the British School (The Sphere 1958), she now overshadowed her late father (Figure 4).

Women and World War II: Gender and Status

The negative behaviour of Kenyon’s male colleagues, the criticisms, her abrupt loss of status and Kenyon’s own apparent acceptance of events needs to be considered within the context of the ambiguities, fears and gender fluidities experienced during and after World War II (Rose 2003: 25, 108–110; Summerfield 1998: 82). In archaeology, as throughout British society, the emergence of the Home Front and the absence of men on war service offered women opportunity and authority. Women played a vital role in rescue excavations and began to find their voice; at the Conference on Future of Archaeology, only 3 out of 29 papers were given by women, but in the discussions 42% of the contributions were by women (Diaz-Andreu and Stig Sorensen 1998: 18). The high female presence in the CBA represented major progress for women in British archaeology and recognition of their abilities as professionals: not just excavators, but educators, administrators and scholars.

Educated middle-class women committed to public service were indispensable to the war effort, often occupying positions of leadership (Hinton 2002: 3), but were seldom accorded an equivalent status to men. Courage, effort and self-sacrifice were expected of women who stepped across the gender boundary into war work, but such participation was always viewed and presented to them as temporary (Summerfield 1998: 82). Kenyon was probably aware that her power as Acting Director was only for a short time, and she, like many other women in war-time, strove to perform to and even surpass idealised masculine standards (Summerfield 1998: 137). The idea of women participating in the war effort could produce distrust and fear in those who preferred conventional gender relationships: both men and women (Rose 2003: 111). There was much resentment of ‘petticoat government’ (Hinton 2002: 98). Strong echoes of these attitudes are displayed in the hostility towards Kenyon as a woman in authority, speaking publicly about state funding, and the interfering ‘ladies’ of the CBA. Women in uniform gave the appearance of female emancipation and a veneer of sexual equality (Morgan and Evans 1993: 80), but caused anxiety and uncertainty (Rose 2003: 122–123). Fascinating insight into contemporary attitudes is given by Nicholas Thomas, who met Kenyon in 1943:

‘My mother and I were confronted by a person who appeared to be a sailor – blue uniform, medal ribbons, everything. But upon rising from behind an imposing desk, a skirt was immediately revealed; the person was Kathleen Kenyon, of course, the wartime Acting Director of the Institute and wearing her high-ranking Red Cross officer’s uniform’ (Thomas, Hutchinson and Gilbert 2013).

War had a positive effect on gender relations, but did not involve the removal of the gender hierarchy. As Britain began to win the war, women were expected to return to their pre-war lives and ‘the home’. Kenyon was not alone in her loss of status; women’s wartime opportunities and authority were lost to the ‘regendering’ of the labour market as men returning from service were privileged for jobs (Summerfield 1998: 209). The loss of Kenyon’s job as Acting Director to Childe, could be seen in this light – regarded as appropriate and justifiable by male colleagues, notably the recently demobbed Worsley. Kenyon’s dedicated war-work indicates a strong sense of patriotism and duty; she may have found it difficult to express her frustrations in the face of such social conventions. Her appointment as lecturer in 1948, should however, be seen as a clear sign of continuing progress in archaeology: her male colleagues might not have been ready to recognise her authority, but they could recognise her talent and professionalism; the strides made in female involvement in archaeology between the wars had not been in vain.

Women responded to the opportunities and challenges of war differently. Some embraced them, others resented war-time service and were eager to return to their old lives; there was no single female experience or gender construct (Summerfield 1998: 273). Women did not always support women; there was often resentment from women towards other women in authority and the ‘bossy’ woman was demonised by both genders (Summerfield 1998: 166). Eates’ criticisms (1944) of Kenyon were very much in this spirit and warn that we should not expect to see an idealised ‘sisterhood’ of early female archaeologists, for women too, reflect prejudices of their time. Kenyon was frequently accused of being ‘authoritarian’, ‘tactless’ and with ‘tendency towards bossiness’ (Mallowan 1977: 240) according to negative post-war gender-judgements of strong women in authority. The judgements still colour narratives about her today; they are overdue a revision.

Conclusion

Examination of Kenyon’s career as Secretary and Acting Director of the Institute of Archaeology has provided insight into the full range of her talents and versatility as an archaeological practitioner and a better understanding of the extent of her contributions to the British archaeological community and culture. She had a career that few of her contemporaries could match, which she created by seizing the opportunities available to women at this time. Like her mentor Verney Wheeler, she made efforts to share these opportunities with other women, encouraging individuals and promoting a wider culture of female practice within archaeology. Kenyon, like many other New Women, challenged contemporary gender boundaries and exploited gender fluidities to step into traditionally male professional spaces and authority in ground-breaking ways; the contemporary media, sensitive to complex gender currents, acknowledged this during her life-time, emphasising the novelty of female archaeological practitioners and their importance as public role models and pioneers. Kenyon portrayed herself as ‘genderless’ as an archaeologist, denied discrimination and tolerated it when she experienced it, perhaps because women of her generation and class chose to define themselves in masculine terms; they were committed to meritocracy and success within a male-defined framework where discrimination went unacknowledged. They also lacked a distinctively feminist language with which to articulate and challenge prejudice; it is interesting to note that Kenyon stated her beliefs about discrimination against women in authority in 1970, when such a language was developing.

Between the wars, women made great strides in female emancipation; progress was particularly strong in penetrating organisations and institutions, both in the workplace and outside, and creating cultures more amenable to female capability, leadership and decision-making, although ‘regendering’ professional changes post-war were to the detriment of female emancipation. We should take care not to let discrimination against women in power, widespread in contemporary attitudes, obscure the real progress made by women in the inter-war period. They participated in professionalising archaeological practice and archaeological culture in general, notably the strong and consistent presence of women in both the established Society of Antiquaries and the innovative Council for British Archaeology. Women’s history reveals that progress in emancipation frequently takes unexpected forms; in archaeology, examination of Kenyon’s administrative career has revealed that progress was not just about individual successes, of which she was a stellar example, but also joint female action to gain a stronger foothold in archaeological culture and normalise women’s abilities and authority within it.

Notes

- R.E.M Wheeler to Kathleen Kenyon, 31st May 1935. UCL Institute of Archaeology: Kenyon Staff Record. ⮭

- The Wheeler-Kenyon Method originated from the work of the Wheelers at Verulamium (1930–1935) and was later refined by Kenyon during her excavations at Jericho (1952–1958). The system involves digging within a series of squares of varying size set within a larger grid. This leaves freestanding walls of earth or ‘balks’ that allow objects or features to be compared to adjacent layers of earth (‘strata’). It was believed that this approach allowed more precise stratigraphic observations than earlier ‘horizontal exposure’ techniques which relied on architectural and ceramic analysis. ⮭

- See Memorandum, Principal of the University of London 1934: 38. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 1. ⮭

- See Management Committee Minutes 2nd June 1943: 3, UCL Institute of Archaeology. ⮭

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

1 Anon 1937 Introductory Note. First Annual Report of the University of London Institute of Archaeology, 7–8.

2 Anon 1938a The Opening of the Institute. Second Annual Report of the University of London Institute of Archaeology, 9–17.

3 Anon 1938b List of Lectures held during the Session 1937–1938. Second Annual Report of the University of London Institute of Archaeology, 16–18.

4 Anon 1947 Session 1938–9 and the War Years. Third Annual Report of the University of London Institute of Archaeology, 7–11.

5 Anon 1948 Management Committee Membership. Fourth Annual Report of the University of London Institute of Archaeology, 1.

6 Bingham, A 2004 ‘An Era of Domesticity?’ Histories of Women and Gender in Interwar Britain. Cultural and Social History, 1(2): 225–233. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1191/1478003804cs0014ra

7 Branson, N 1975 Britain in the Nineteen Twenties. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

8 Carr, L C 2012 Tessa Verney Wheeler. Women and Archaeology Before World War Two. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:osobl/9780199640225.001.0001

9 Champion, S 1998 Women in British Archaeology. In: Diaz-Andreu, M and Stig Sorensen, M L (eds.), Excavating Women. A History of Women in European Archaeology, 175–197. London, New York: Routledge.

10 Clapham, A W 1943 Anniversary Address. The Antiquaries Journal, 23(3–4): 87–97. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500016358

11 Clapham, A W 1944 Anniversary Address. The Antiquaries Journal, 24(3–4): 85–93. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500016553

12 Colpus, E 2018 Women, Service and Self-Actualization in Inter-War Britain. Past and Present, 238: 197–232. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/pastj/gtx053

13 Coventry Standard 1943 Post-War Red Cross Work Support of Youth. Coventry Standard, 27 February, p. 6.

14 Daily Mail Atlantic Edition 1927 How Feminine Oxford Has Enjoyed past Term. By a Woman Graduate. Daily Mail Atlantic Edition, 3. 13 December.

15 Dallas, V 1938a Dallas to Kenyon 30 January 1938. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, 1.

16 Dallas, V 1938b Dallas to Kenyon 31 January 1938. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, 1.

17 Dallas, V 1945 Dallas to Kenyon 31 July 1945. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, 1.

18 Davis, M C 2008 Dame Kathleen Kenyon. Digging up the Holy Land. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

19 Dever, W G 2004 Kathleen Kenyon 1906–1978. In: Cohen, G M and Joukowsky, M S (eds.), Breaking Ground. Pioneering Women Archaeologists, 525–553. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

20 Diaz-Andreu, M and Stig Sorensen, M L 1998 Excavating Women. Towards an engendered history of archaeology. In: Diaz-Andreu, M and Stig Sorensen, M L (eds) Excavating Women. A History of Women in European Archaeology, 1–28. London, New York: Routledge.

21 Dundee Evening Telegraph 1947 Digging Up The Past. Dundee Evening Telegraph, 2. 2 December.

22 Dyhouse, C 1995 No Distinction of Sex? Women in British Universities 1870–1939. London: UCL Press.

23 Eates, M 1944 Eates to Wheeler 16 December 1944. Museum of London Archives, DC4/18.

24 Evans, C 2008 Archaeology against the State: Roots of Internationalism. In: Murray, T and Evans, C (eds.), Histories of Archaeology. A Reader in the History of Archaeology, 222–237. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

25 Evans, J D 1987 The First Half-Century – and After. Bulletin of the Institute of Archaeology, 24: 1–26.

26 Fox, C 1949 Miss K. Kenyon. Secretary of the Institute, 1935–48. Fifth Annual Report of the University of London Institute of Archaeology, 65–67.

27 Hamilton, S 2007 Women in Practice: Women in British Contract Field Archaeology. In: Hamilton, S, Whitehouse, R D and Wright, K I (eds.), Archaeology and Women. Ancient and Modern Issues, 121–146. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

28 Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail 1936 Secrets of a Ruined City. Excavations at Uriconium. Hartlepool Northern Daily Mail, 2. 11 September.

29 Hawkes, J 1982 Mortimer Wheeler. Adventurer in Archaeology. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

30 Hinton, J 2002 Women, Social Leadership and the Second World War: Continuities of Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199243297.001.0001

31 Kenyon, F 1936 Anniversary Address. The Antiquaries Journal, 16(3): 249–259. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500027748

32 Kenyon, F 1939 Anniversary Address. The Antiquaries Journal, 19(3): 247–259. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500007800

33 Kenyon, K M 1935 Kenyon to Wheeler 13 June 1935. UCL Institute of Archaeology: Kenyon Staff Record.

34 Kenyon, K M 1936a Kenyon to Webb, Secretary to the University Senate 6 April 1936. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 5, box 1.

35 Kenyon, K M 1936b Kenyon to Peers 16 April 1936. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/5.

36 Kenyon, K M 1936c Kenyon to Dove 23 1 October 1936. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 5, box 1.

37 Kenyon, K M 1937a Kenyon to Kingsford 8 February 1937. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/18.

38 Kenyon, K M 1937b Kenyon to Mattingly 21 December 1937. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/155.

39 Kenyon, K M 1937d Kenyon to Perowne 12 December 1937. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 4.

40 Kenyon, K M 1938a Kenyon to Mattingly 18 January 1938. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/162.

41 Kenyon, K M 1938b Kenyon to Cowen 3 March 1938. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/59.

42 Kenyon, K M 1938c Kenyon to Duke of St Albans 6 May 1938. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/89.

43 Kenyon, K M 1938d Kenyon to Collingwood 8 September 1938. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/76.

44 Kenyon, K M 1939b Kenyon to Pearson 6 April 1939. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/106.

45 Kenyon, K M 1939c Kenyon to Macmillan 17 April 1939. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/115.

46 Kenyon, K M 1940a Kenyon to Musson 7 February 1940. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/129.

47 Kenyon, K M 1940b Kenyon to Pearson 25 May 1940, Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/108.

48 Kenyon, K M 1942 Kenyon to Baker 2 January 1942. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/128.

49 Kenyon, K M 1943a Kenyon to Crowfoot 17 February 1943. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files, 3(1–3).

50 Kenyon, K M 1943b Kenyon to Glanville 23 March 1943. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files, 3(1–3).

51 Kenyon, K M 1943c Kenyon to Secretary of State for the Colonies 26 July 1943. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files, 3(1–3).

52 Kenyon, K M 1943d Archaeology as a Career for Women. Women’s Employment, 4–5. Jan 7.

53 Kenyon, K M 1944 Kenyon to Worsley 19 October 1944. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 5.

54 Kenyon, K M 1952 Beginning in Archaeology. London: Phoenix House.

55 Kenyon, K M 1970 The Galton Lecture 1969. Women in Academic Life. Journal of Biosocial Science Supplement, 2: 107–118. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S002193200002352X

56 Kenyon, K M 1977 Obituaries, Mortimer Wheeler. Levant, 9(1): iii. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1179/lev.1977.9.1.i

57 Light, A 1991 Forever England. Femininity, Literature and Conservatism between the Wars. London: Routledge.

58 Lincolnshire Echo 1944 Red Cross Rally of Youth. Lincolnshire Echo, 3. 29 June.

59 Mallowan, M E L 1977 Mallowan’s Memoirs. London: Collins.

60 Market Harborough Advertiser and Midland Mail 1944 Treasure Trove. Market Harborough Advertiser and Midland Mail, 1. 12 May.

61 McKibbin, R 1998 Classes and Cultures in England. 1918–1951. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198206729.001.0001

62 Moorey, P R S 1992 British Women in Near Eastern Archaeology: Kathleen Kenyon and the Pioneers. Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 124(2): 91–100. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1179/peq.1992.124.2.91

63 Morgan, D and Evans, M 1993 The Battle for Britain. Citizenship and Ideology in the Second World War. London, New York: Routledge.

64 Morris, R 2007 The Antiquaries and Conservation of the Landscape, 1850–1950. In: Pearce, S (ed.), Visions of Antiquity. The Society of Antiquaries of London 1707–2007, 306–331. London: The Society of Antiquaries.

65 Moshenska, G 2013 Reflections on the 1943 ‘Conference on the Future of Archaeology’. Archaeology International, 16: 128–139. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ai.1604

66 Nottingham Journal 1942 British Red Cross Training Scheme for Notts Youth. Nottingham Journal, 2. 19 May.

67 Nottingham Journal 1943 Reconstruction Plans in Europe. Nottingham Journal, 4. 22 March.

68 Parr, P 2004 Kenyon, Dame Kathleen Mary (1906–1978). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

69 Peers, C 1936a Peers to Kenyon 21 April 1936. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/6.

70 Peers, C 1936b Obituary notice. Mrs Mortimer Wheeler. Antiquaries Journal, 16(3): 327–328. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003581500027906

71 Perowne, E S F 1936a Perowne to Kenyon 20 March 1936. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 4.

72 Perowne, E S F 1936b Perowne to Kenyon 31 March 1936. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 4.

73 Prag, K 1992 Kathleen Kenyon and Archaeology in the Holy Land. Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 124(2): 109–123. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1179/peq.1992.124.2.109

74 Rose, S O 2003 Which People’s War? National Identity and Citizenship in Britain 1939–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

75 Sparks, R T 2007 Flinders Petrie and the Archaeology of Palestine. In: Sparks, R T (ed.), A Future for the Past. Petrie’s Palestinian Collection. An Exhibition Held in the Brunei Gallery, 1–12. London: Institute of Archaeology University College London.

76 Sparks, R T 2013 Publicising Petrie: Financing Fieldwork in British Mandate Palestine (1926–1938). Present Pasts, 5(1): 1–15. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/pp.56

77 Sparks, R T and Ucko, P J 2007 A History of the Petrie Palestinian Collection. In: Sparks, R T (ed.), A Future for the Past. Petrie’s Palestinian Collection. An Exhibition Held in the Brunei Gallery, 13–24. London: Institute of Archaeology University College London.

78 Stig Sorensen, M L 1998 Rescue and Recovery. On historiographies of female archaeologists. In: Diaz-Andreu, M and Stig Sorensen, M L (eds.), Excavating Women. A History of Women in European Archaeology, 31–60. London, New York: Routledge.

79 Stout, A 2008 Creating Prehistory. Druids, Ley Hunters and Archaeologists in Pre-War Britain. Oxford: Blackwell.

80 Summerfield, P 1998 Reconstructing Women’s Wartime Lives. Discourse and Subjectivity in Oral Histories of the Second World War. Manchester, New York: Manchester University Press.

81 Surrey Mirror 1945 Archaeologists visit Godstone and Oxted. The scientific Land Planning of an Ancient Village. Surrey Mirror, 3. 31 August.

82 The Sphere 1958 The Turn of the Year in the Holy Land. The Sphere, 24–25. 11 January.

83 Thomas, N, Hutchinson, O and Gilbert, L 2013 Alumni Reflections. Archaeology International, 16: 140–147. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5334/ai.1604

84 Thornley, I 1938 Thornley to Kenyon 13 May 1938. Institute of Archaeology Library Archive, D/168.

85 Western Gazette 1936 The Late Mrs R.E. Mortimer Wheeler. A permanent memorial. Fund opened. Western Gazette, 16. 19 June.

86 Wheeler, R E M 1935a Wheeler to Kenyon 31 May 1935. UCL Institute of Archaeology: Kenyon Staff Record.

87 Wheeler, R E M 1935b Wheeler to Kenyon 21 June 1935. UCL Institute of Archaeology: Kenyon Staff Record.

88 Wheeler, R E M 1935c Wheeler to Kenyon 8 July 1935. UCL Institute of Archaeology: Kenyon Staff Record.

89 Wheeler, R E M 1936 Wheeler to Kenyon 6 January 1936. UCL Institute of Archaeology: Kenyon Staff Record.

90 Wheeler, R E M 1955 Still Digging : Interleaves from an Antiquary’s Notebook. London: Michael Joseph 1955.

91 Wheeler, R E M 1970 Wheeler to Kenyon 18 March 1970. UCL Wheeler Archive B/4/9.

92 Wheeler, R E M 1973 Wheeler to Kenyon 5 October 1973. UCL Wheeler Archive B/4/9.

93 Woollacott, A 1998 From Moral to Professional Authority: Secularism, Social Work and Middle-Class Women’s Self-Construction in World War I Britain. Journal of Women’s History, 10(2): 85–111. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2010.0388

94 Worsley, S J 1936 Worsley to Kenyon 19 November 1936. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 5.

95 Worsley, S J 1944a Worsley to Peers 19 September 1944. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 5.

96 Worsley, S J 1944b Worsley to Kenyon 11 October 1944. UCL Institute of Archaeology Archives, Senate House Files 5.