Professor Geoffrey Martin, 1934–2022

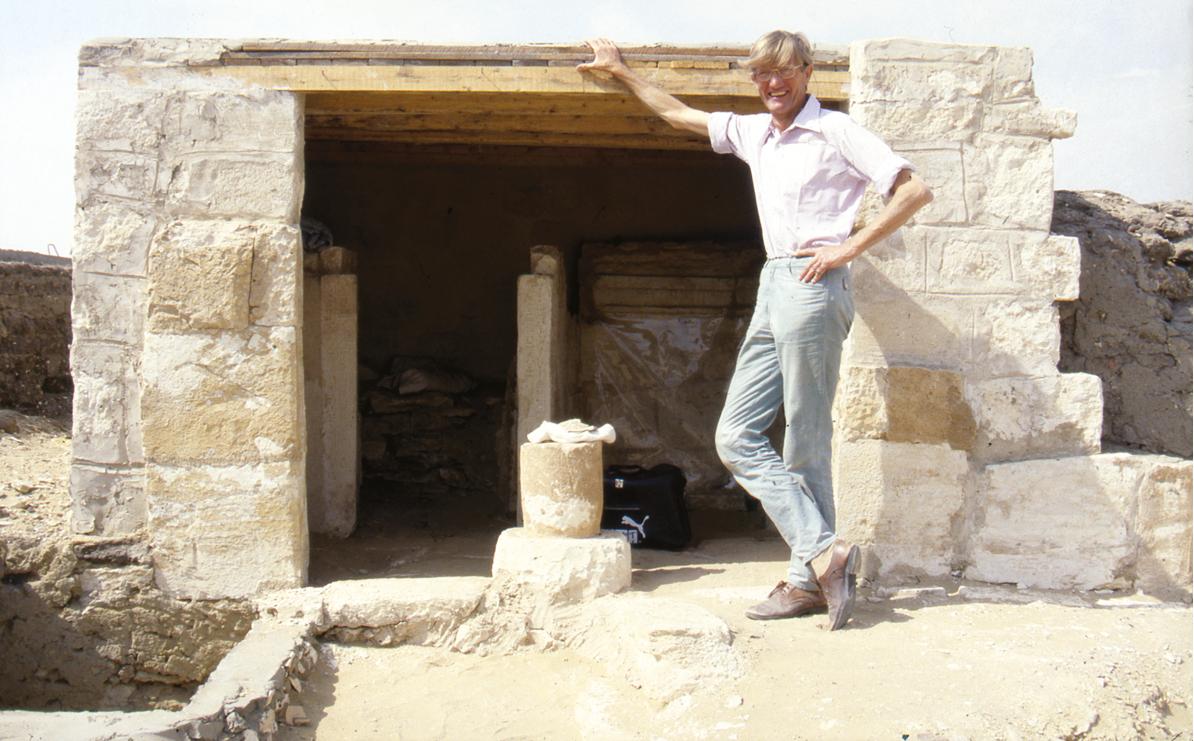

Geoffrey Martin passed away on 7 March 2022, leaving us an extraordinary record of research publications and fieldwork in Egypt and Sudan over six decades. These active resources for the future extend beyond our personal sense of loss for a friend and teacher. His collegiate joint work with Egyptian and Sudanese colleagues in archaeology, both in the field and in museums (see Figure 1), remains a vital example for archaeologists from outside who are guests in the region.

A UCL alumnus, Geoffrey began his university studies in 1963 with a Bachelor of Arts at the Department of History. Arnaldo Momigliano held the Chair of Ancient History then, applying an unparalleled breadth of learning – Geoffrey once recalled to me that the reading lists demanded engagement with whatever had been written on the particular topic, be it in Swedish or Russian. He did not mention how he and his fellow students managed this, but he shared the memory in his typically exuberant enthusiasm for knowledge and what was written. As a committed book-lover, he amassed a vast library of his own. He had a deep – and far too rare – appreciation for the essential role of librarianship in higher education and research, and he winced visibly at any sign of damage to a volume. For his Masters degree, Geoffrey moved in 1966 to Cambridge and took up the Lady Wallis Budge Junior Fellowship in Egyptology at Christ’s College, receiving his doctorate in 1969. Within a couple of years he had published from that dissertation his comprehensive corpus of seal-amulets with names, a Who’s Who of titled women and men in the nineteenth to sixteenth centuries bce.

As a reliable dataset central to our knowledge of Middle Bronze Age Egyptian society and economy, ‘Martin 1971’ continues to have an impressive impact on current historical and archaeological studies of the wider region. His first articles from doctoral research are on the curious choice by several rulers of Gebeil/Byblos, port for the Lebanon cedar trade, to have Egyptian-style scarab-shaped seals inscribed with their title and name in Egyptian language and in hieroglyphs. Through the decades Geoffrey would return to these inter-regional signals from Gebeil, publishing new examples as he encountered them.

Already during his undergraduate years at UCL, he had joined a Nile Valley excavation team in one of the last rescue archaeology seasons at the Middle and Late Bronze Age fortress at Buhen, Sudan, under the direction of Brian Emery – the UCL Egyptology Professor – for the London-based Egypt Exploration Society (EES). Emery moved to fieldwork on Early Bronze Age cemeteries at Saqqara, Egypt, where Geoffrey became the first Field Assistant appointed by the EES. The role involved both excavating and preparing reports, tasks he would continue to fulfil over the many years ahead for the EES at Saqqara until 1998 and for other fieldwork sponsors thereafter.

In 1970 his work took decisive new turns. He received funding to document finds in The Egyptian Museum, Cairo from the family tomb of Akhenaten at Amarna, shifting his focus to Late Bronze Age Egypt. Geoffrey also became Lecturer in the Department of Egyptology (a separate unit until the Institute of Archaeology became part of UCL), advancing to Reader in 1979 and becoming Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology in 1988, the post he held until his retirement in 1992. As the Department was then next door to the UCL Egyptian Museum (now The Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology), he was able to include museum classes with object-based learning, as UCL students of the day such as Dr Robert Morkot have vividly described to me. Together with research assistants, he contributed catalogues of important parts of the Museum collection. Besides supporting learning directly here at UCL, in these teaching years he published a periodic list of higher degrees under way across England, Scotland and Wales.

In 1975 Geoffrey began a long and fruitful international co-operation with Dr Maarten Raven at the National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden (the Netherlands) to co-direct excavation of the Late Bronze Age royal court cemetery in south Saqqara, exploited by collectors of antiquities in the 1820s but since lost to view. Half a century of fieldwork has revealed a series of the temple-size chapels over the tombs of high officials of Tutankhamun and his successors; the most famous are his general Horemheb (later king) and his treasurer Maya. More evocative still are the smaller chapels scattered between and around them (Figure 1). His parallel research in museums worldwide resulted in a second corpus, this time of the loose blocks known to come from Saqqara tombs (1987). In his 1991 book Hidden Tombs of Memphis, Geoffrey provided access to the fieldwork results for the wider public that he appreciated as keenly as the university researchers. With the late Professor Ali el-Khouly he conducted fieldwork in the tomb for the family of King Akhenaten at Amarna, published jointly in 1987; he also documented and published (1989) the depictions in the tomb, with some of the most striking images of grief in the art of Egyptian kingship.

In ‘retirement’ Geoffrey continued energetic involvement in fieldwork as co-director with colleagues on new projects, now farther south in Upper Egypt, at Thebes: with Nicholas Reeves on the Amarna Tombs Project and with Jacobus van Dijk on the Cambridge Expedition to the Valley of the Kings, recording the tomb cut for Horemheb after he became king. Most recently he worked with Piers Litherland and Judith Bunbury on the joint expedition of the New Kingdom Research Foundation and Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities. At Thebes, as at Saqqara, Geoffrey kept his focus on epigraphy, working with the inscribed traces to connect with ancient people by name or figure, and on a practical level to produce drawings that result in publications – our access to ancient people. In his stream of monographs and articles, we can continue to enjoy his output. Those of us lucky enough to have known him will find in the reading our consoling memories of intense discussions, entertaining tales and mischievous smiles.

For further obituaries, see: