| Key messages | |

| • | Evidence Cafés can support effective two-way knowledge exchange between practitioners and academics, leading to impact on both practice and research. |

| • | Evidence-based champions (from practice) and research champions (from academia) are key ‘boundary creatures’ (Adams et al., 2013) facilitating two-way flow of evidence between practice and research. |

| • | Evidence Cafés use discussion objects, boundary objects tailored to the research topic, that trigger meaning making and evidence sharing between practice and academia while helping to break down challenges of competing motivations and timings, including status (practitioner or researcher) and rank. |

Introduction

The importance of an evidence-based approach to practice is increasingly recognized across public services (health care, management, teaching, policing). This movement seeks to increase the quality and rigour of practice by implementing evidence into practice-based decision-making processes (Horner et al., 2005; Kitson et al., 1998; McKibbon, 1998). However, problems frequently occur when translating research evidence for practice purposes and applying that research into practice contexts (Kitson et al., 1998). There is a growing push for evidence-based practice to take a more balanced participatory approach between academics and practitioners (Lum, 2014; Rice, 2007). This requires recognizing and valuing not only research evidence, but also practitioners’ understanding and practice-based evidence. It also requires a reassessment of notions of knowledge quality, which have been traditionally bound to academic notions of research rigour.

Preconceptions of what ensures quality in evidence have produced barriers in attempts to make connections between research and practice evidence. It is these tensions that can often translate into the knowledge-exchange process, where notions and protective perceptions of rigour and risk of biases continue. For example, Grand (2015) highlights the view from researchers that being involved in engagement can be bad for a career, and can reduce colleagues’ respect for their work. Conversely, police practitioners have noted (Adams et al., 2018a, 2018b) that engagement with evidence-based-practice research has caused colleagues to dispute their ability to make decisions that are relevant to practice needs. Academic research uses rigorous methods to generate evidence that is theoretically underpinned, but it may lack an authentic understanding of the relevance of this to practice. Drennon (2002), in particular, has argued that research evidence lacks relevance to practitioner needs. Practitioners have evidence of ‘what works’ and insights into why it works, but they may lack the rigour in how to evaluate that evidence to support their practice-based understandings.

Most reviews of research evidence quality and rigour have focused on academic research (Adams and Cox, 2008; Corbin and Strauss, 2015; Henwood and Pidgeon, 1992). The public engagement movement has shifted in notions of knowledge quality to include not only practitioner tacit knowledge but also quality in the processes of co-creating knowledge exchange (Grand, 2015). This has not only included different knowledge owners – researchers, publics, practitioners – but also the processes of co-creating knowledge that are documented in this paper. The importance and role of knowledge exchange have also shifted over recent years. Grand (ibid.) found that the majority of publics perceived influencing policy or policymakers, and driving social change, as key reasons for public engagement. To advance perspectives of evidence quality, we therefore need to incorporate concepts of quality in engagement processes.

There has long been a history documented on the importance of engaging research with practice (ibid.). In 2014, the emphasis on the role of research in triggering and supporting changes in practice was implemented through the Research Excellence Framework (REF). Within this framework, the quality of UK research was directly connected to its ability to link to impacts (HEFCE, 2015). Academic research should be able to connect with and inform practice, providing a robust evidence base on which to build improvements. However, there remain challenges to embedding academic findings in practice. Practitioners may question the validity of recommendations that are heavily theory-driven, and they may not see them as sufficiently relevant to practice. The discourse of academia may not align with the discourse of practitioners, inhibiting the development of a shared understanding and preventing the take-up of research findings. Hall and Tandon (2017) refer to a form of ‘knowledge asymmetry’, when the practitioners who provide the source of knowledge do not benefit from the gathering and organizing of that knowledge. Hall and Tandon’s (ibid.) use of the term ‘knowledge asymmetry’ in this context implies that the knowledge is going only in one direction. It suggests that knowledge is flowing from practice to research but not back again.

In this paper, we review Evidence Cafés as a means to enable knowledge exchange, and evaluate their effectiveness in bridging the gap between research- and practice-based evidence. In particular, this paper evaluates Evidence Cafés as an effective method to promote equitable knowledge exchange to increase impact (both significant and scalable) upon both practice and research.

Background to Evidence Cafés

Evidence Cafés were developed as part of the knowledge exchange research arm of the Centre for Policing Research and Learning (CPRL). The CPRL is a partnership between police forces (currently 20) and the Open University aiming to develop the connection between policing and research, and to support the continuing professional development of police through formal and informal learning.

When reviewing the background to Evidence Cafés, we need to share what we mean by ‘evidence’, as this can have very procedural (for example, evidence in court cases) and quantifiable (that is, only randomized controlled trial evidence) connotations that we need to dispel. This then leads on to detailing background to the breadth of discipline perspectives, both empirical and practical, that we feel should be incorporated and supported by Evidence Cafés.

Evidence levels and types: What is data, information and knowledge?

Philosophical literature has long debated concepts of knowledge and information, which has led on to the more elusive and complex concepts of wisdom and enlightenment. Expressed simply, evidence can be seen at different levels of data, information and knowledge. Each level could be viewed as a stage of depth in analysis, when increasing levels of generalized interpretation and processing are applied. For example, 14031879 is data; it is a string of digits. Apply a formatting process to the digits to produce 14-03-1879, and the data becomes information: a date expressed in UK DD-MM-YYYY format. Knowledge would emerge from web research into this date, which would identify that this was Einstein’s date of birth.

The word ‘data’ comes from the Latin ‘datum’, a fact or, more interestingly, a starting point. Data are often connected to empirical evidence. While the term goes back centuries, it is not surprising that it became more widely used with the birth and mass consumption of personal computers. Information and knowledge are often described as evidence for change within an organization.

Added to notions of evidence depth are the different sources and types of evidence, from experiential to research, which could be described along a continuum of rigour in their systematic collection and interpretation. However, it is important not to associate rigour with importance, since experiential evidence can reflect highly valuable and influential evidence in national debates. Although these concepts (data, information and knowledge) have been tied strongly to research, they are still widely used in practice frames to describe a variety of types of evidence from experiential/tacit understanding, to procedural and research insights. With the growing importance of evidence-based practice within the police domain, there has been a shift to prioritize quantitative research knowledge (Sherman and Strang, 2004; Sherman et al., 2005) over tacit and experiential knowledge. However, the evidence-based practice movement has complicated this debate further with value statements about the superiority of one methodology (randomized controlled trials) over another, regardless of the reviews of method effectiveness to answer different practice-related questions (Kitson et al., 1998). Evidence Cafés address the tension between a historical tendency to assign greater weight to quantitative research evidence in preference to tacit and experiential evidence by enabling participants to connect up these different notions of evidence.

Facilitating the equitable exchange of evidence

Evidence Cafés provide a means for practitioners and researchers to connect up research evidence with practice-based evidence. The Evidence Café approach to knowledge exchange is built on the principles from the worldwide Café Scientifique movement (Grand, 2015). Evidence Cafés draw on these principles, placing at their core concepts of two-way knowledge exchange rather than one-way knowledge transfer.

In the next section, we describe the methods and methodology, and then present three case studies that show the impact of motivation and timing on the flow of evidence, and the effectiveness of knowledge exchange through Evidence Café methods.

Evidence Café evaluation: Methods and methodology

The format of an Evidence Café has several key characteristics:

-

It focuses on a research topic that is relevant to the host organization.

-

Participants are selected by the evidence-based champion (EBC) from the practice-based host organization, and drawn from practitioners from the host organization. Additional participants may be invited from other related organizations and/or community members who have some connection to the research topic under discussion. Evidence Cafés are not open to the general public.

-

It is grounded in concepts of evidence-based practice, aiming to integrate robust research evidence and practice-based insights to generate measurable impact on both host organization and academic research.

-

It is co-facilitated by an EBC from the host organization, and a research champion (RC) who is an academic specializing in knowledge exchange. Evidence Cafés are not ‘led’ by an academic.

-

It uses a discussion object, tailored to the research topic, to facilitate meaning making and the development of changed understandings.

Table 1 lists the roles and artefacts, and how they interact in the activities during an Evidence Café.

Roles, artefacts and activities during an Evidence Café

| Key roles and artefacts | Activities during the Evidence Café | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research Champion (RC) | Introduce Evidence Café (jointly with EBC), explaining how the Evidence Café will run | Facilitate discussions and use of discussion object for reflective meaning making | Facilitate feedback round-up session | Record activities and discussions for final report and collect research data (optional) |

| Evidence-based Champion (EBC) | Introduce Evidence Café (jointly with RC); contextualize the research topic in terms that are relevant to practice | Facilitate discussions and use of discussion object for reflective meaning making | Facilitate feedback round-up session | |

| Academic expert | Present research | Facilitate use of discussion object for reflective meaning making | Facilitate feedback round-up session | Collect data (optional) |

| Participants | Discuss topic, offering personal experience facilitated by discussion in groups | Feedback to whole group | ||

| Discussion object artefact | Triggers discussion and meaning making among participants | |||

Evidence Cafés are held in informal venues, or meeting rooms with an informal layout, with coffee and biscuits. Participants are encouraged to refill coffee cups and move around, rather than remain sitting formally at their tables. The deliberate informality aims to break down barriers due to status, and to encourage two-way dialogue to facilitate conversations around the topic. Typically, an Evidence Café has between 25 and 30 participants and lasts around two hours, although they can run over a full day, or two days, if larger numbers of participants are involved. More participants have been found to require more facilitators.

Once a research topic has been selected, the RC liaises with the EBC from the host organization to align the goals for the Evidence Café and ensure that the research matches the practice context. This takes place across five stages:

-

Design discussion object: The RC identifies and works with the academic subject matter expert(s) to design the discussion object and meaning-making activities to trigger dialogue and frame the knowledge exchange in liaison with the EBC. The EBC identifies participants and champions from the host police force, and potentially also from neighbouring police forces and the community. Only those police forces who were members of the CPRL during this time period were eligible to host or attend Evidence Cafés. This is captured in a draft ‘expectations form’.

-

Tailor the discussion object: The RC, EBC and academic subject matter expert work iteratively to plan the Evidence Café and prepare the materials. This is captured in the final ‘expectations form’.

-

Deliver the Evidence Café.

-

Prepare and submit report: The outcomes of the Evidence Café are written up, collated and turned into a PDF report. After a quality assurance (editing) process, this report is delivered to the host organization.

-

Review: Meet with the host organization organizer to review next steps, make recommendations and agree case study testimonial for impact.

Over the course of the research, the discussion object emerged as key to facilitating equitable knowledge exchange. The two stages during which the expectations document is developed and refined ensure that the discussion object is appropriate for practice, yet is also relevant to the academic research topic under discussion. Previous discussion objects are often reused and, if necessary, adapted.

During a typical Evidence Café, the event begins with an introduction from the RC and EBC, followed by a presentation from the academics of the rationale underpinning the research, often with a demonstration on a big screen. The discussion object is introduced by the academic and RC, who facilitate reflective meaning making with the participant groups, with one discussion object in each group. The mechanism for reflective meaning making depends on the topic under discussion, and the discussion object in use.

After discussing in groups, the groups then report back and engage in a whole-group discussion to share their findings and explore how the emerging meaning making fits in with practice and research.

Data collection methods

We collected data at each Evidence Café using a variety of methods:

-

audio recordings – transcribed and anonymized

-

discussion objects – photographed and/or digitized depending on the discussion object

-

flip chart/magic whiteboard notes – photographed and digitized

-

online survey – to capture views and perspectives before and after the Evidence Café

-

participant notes – either handwritten or using Livescribe recording pen

-

Post-it note feedback at the end – reflect on: three things you liked, three things you thought could be improved, three things you would like more of

-

still photographs

-

Twitter – #WeCops debate run two hours prior to an Evidence Café to identify evidence-based practice themes to feed into the subsequent Evidence Café

-

video:

-

camcorder, either set up in a corner of the room on a tripod, or handheld

-

iPad, handheld

-

Flip Video, handheld.

-

The choice of data recording method varied between Evidence Cafés depending on the participants and the choice of topic.

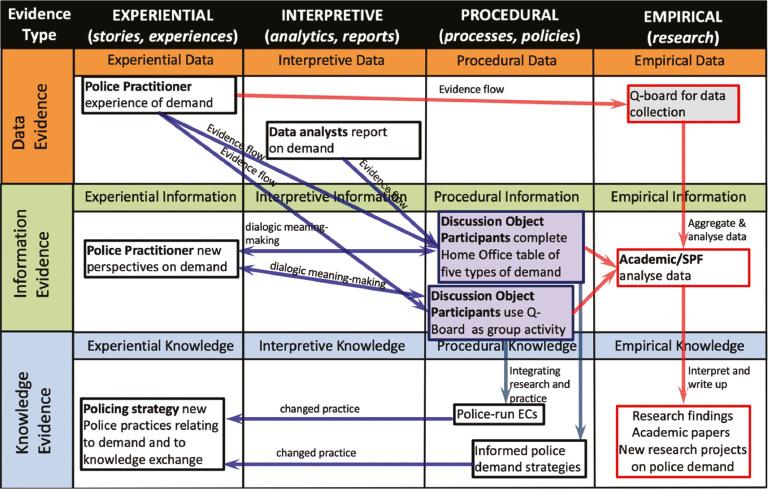

Developing a discussion object: The evidence typology

Each discussion object was tailored to match the topic of the Evidence Café. For example, in Evidence Café 10, we developed an evidence typology as a discussion object to support participants to identify issues around translating the masses of policing data into useful information that could lead to knowledge and insights into how to improve police practice, as well as integrating different types of evidence from research with policing processes and experience evidence. The evidence typology also allowed participants to classify levels of evidence by increasing depth of analysis:

-

data – raw data without meaning, for example, numbers, words

-

information – data with attached meaning for ‘who, what, where’

-

knowledge – information with stories, insight, know-how for ‘why and how’.

The evidence typology then enabled participants to classify evidence on a continuum of rigour (of equal importance) for types of evidence:

-

experiential – for example, stories

-

interpretive – for example, expert reports, analytics

-

procedural – for example, policies and processes

-

research/empirical.

For each evidence type, there is a different level of analysis that has been achieved. Types and levels of analysis link together through the typology (see Figures 1a and 1b).

The evidence typology brought together different notions of evidence, enabling participants to find connections between them without allowing any one particular type of evidence to dominate. Participants engaged deeply with the typology; the EBC from Evidence Café 10, who was a high-ranking officer in charge of teams of data analysts, reported that his staff subsequently integrated the evidence typology into their working practices:

There was some really good conversation after the session, and I can see some copies of the typology about the office! (EBC, Evidence Café 10)

During Evidence Café 10, one data analyst commented in the group discussion that they were collecting large amounts of a particular category of raw data, and turning it into reports that were then submitted and filed with no further impact. They found this very demotivating. The EBC, who was the high-level boss of the team, was shocked, having some months previously issued a directive that this unproductive activity should cease. Informed by the Evidence Café, the EBC determined to reissue the directive and take steps to ensure that it was filtered to all levels in the organization. In this example, the meaning-making activity around the evidence typology highlighted an issue that data were being processed into information, but that information was not being interpreted into useful knowledge. The informal and equitable methods of the Evidence Café, where all voices carry equal weight, enabled meaningful communication between a team member of low status and the officer in overall charge.

In later feedback, the EBC from Evidence Café 10 described how that force planned to use the evidence typology to support changing work practices:

In terms of using the material presented during the Café, I will certainly be using it as part of presentational and training material for the development of our ‘organisational learning’ function. This is a development of our current performance/corporate services function to more effectively harness learning in a number of formats be that internal, academic or policy. I see the typology as particularly useful in being able to demonstrate the transition from an older way of working (late-‘90s performance targets environment) into a more holistic arena which triangulates qualitative and quantitative data to provide a compelling narrative in context. (EBC, Evidence Café 10)

In view of the effective way that the evidence typology enabled police participants to classify evidence as different types of data, information and knowledge, it was redeployed as the discussion object in two other Evidence Cafés on different topics, hosted by other police forces. The Evidence Café themes were: (1) how to identify and make use of different forms of data collected around antisocial behaviour; and (2) how to evaluate the success of initiatives to stop young high-harm offenders from reoffending. The evidence typology was effective in both these Evidence Cafés.

The power of the evidence typology as discussion object in enabling participants to unpick concepts of data, information and knowledge in a range of policing contexts prompted us to use it as an analysis framework within which to analyse the evidence from the case studies. We combined this with a grounded thematic analysis of the data we had collected from the Evidence Cafés, and we used the evidence typology to classify the flows of evidence from data to information and knowledge that we identified. The analysis then allowed us to map out the level of knowledge transfer and knowledge exchange between research and practice, as well as between practice and research. We also collected evidence of changed understanding, and of impact on practice and processes, for both the police and academia. This analysis identified a key challenge around conflicting motivations and timings, and their impact on whether or not two-way knowledge exchange occurred.

Case study analysis

In the following sections, we draw on the evidence typology analysis of data collected during the 15 Evidence Cafés held over a 20-month period between February 2016 and October 2017. Twelve police forces were involved in these Evidence Cafés, with some police forces hosting more than one Café on different dates, with different participants on different topics. Each Café was held at the headquarters of the host police force so that it was easy for police participants to attend without disrupting their operational roles. The Evidence Cafés were:

-

Evidence-based practice; gathering first accounts from child witnesses (Police Force 2 – 42 participants)

-

Using social technology and crowdsourcing to support community engagement with policing (Police Force 3 – 27 participants)

-

Evidence-based practice; gathering first accounts from child witnesses (Police Force 4 – 11 participants)

-

Leadership and political astuteness (Police Force 5 – 70 participants)

-

Demand management (Police Force 6 – 25 participants)

-

Demand management (Police Force 7 – 31 participants)

-

Ethics in policing (Police Force 8 – 25 participants)

-

Demand management (Police Force 9 – 19 participants)

-

Translating data into useful knowledge using the evidence typology (Police Force 7 – 11 participants)

-

Assessing initiatives to stop young high-harm offenders from reoffending through education/employment (Police Force 10 – 11 participants)

-

Digital forensics (Police Force 1 – 14 participants)

-

Demand management (Police Force 11 – 12 participants)

-

From data to knowledge: making sense of evidence (combined Police Force 8 and Police Force 9 – 24 participants)

-

Demand management (Police Force 12 – 36 participants).

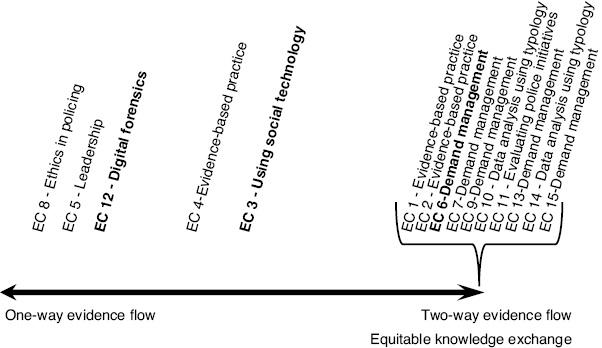

Figure 2 shows the 15 Evidence Cafés on a continuum, ranked according to evidence flow (based upon the typology analysis completed), with Cafés with more one-way evidence flow to the left, and those in which there was a two-way flow resulting in equitable knowledge exchange taking place to the right. The level of knowledge exchange during the Evidence Cafés was assessed through: the level of contributions from participants, post-Café participant feedback, post-Café police force testimonials and evidenced police and academic practice changes attributed to the Café, and the final report.

These Evidence Cafés were held with police forces from across the UK, attended by 378 police officers, police staff and community representatives. These core data were supplemented with feedback from participants and facilitators from further Evidence Cafés: five Cafés run in a university setting (for scholarship and professional development planning); one Café run on the topic of environmental conservation of meadow floodplains; one Café on the topic of managing your multiple sclerosis; and four Cafés run in Africa on migration issues.

While all the data were used to develop the findings, we have selected three case studies as exemplars from across this continuum that showcase these findings. Evidence Café 12 – Digital forensics, Evidence Café 3 – Using social technology, and Evidence Café 6 – Demand management (shown in bold in Figure 2) illustrate the key findings of how conflicting motivations and timing affect the level of equitable knowledge exchange that occurs in Evidence Cafés at different points in the evidence-flow continuum.

Case Study 1: Evidence Café 12 – Minimal evidence flow

Evidence Café 12 was the second Café run at Police Force 1. The first Café held with this force (Evidence Café 1) had delivered high levels of two-way flow of evidence, leading to equitable knowledge exchange. In contrast, Evidence Café 12 did not deliver knowledge exchange. Evidence Café 12 was facilitated by an RC and EBC on the topic of social media as an online tool for evidence capture. The EBC was a senior officer with power to effect change, and the participants were technical and specialized experts in combating cybercrime and digital forensics.

Case Study 1: The process

The Evidence Café began with a presentation from the academics about the rationale underpinning the research, with a demonstration of the software app on a big screen. The discussion object was the software app, and participants were offered iPads running the app, or they could open the app using their police smartphones. After exploring the features in pairs, the group then engaged in a whole-group discussion to explore where this software might fit within their practice. Four academics participated, although the principal investigator with the power to direct the project did not attend. The EBC who facilitated Evidence Café 12 had also facilitated Evidence Café 1, held many months earlier. He was a senior officer in charge of the teams who attended the Cafés. After Evidence Café 1, the EBC initiated a series of ‘Practitioner Cafés’, run using the Evidence Café methods of equitable knowledge exchange that had taken place in the first Café. Thus, this EBC had already contextualized Evidence Café methods for policing practice.

Case Study 1: Analysis

Despite engaging interactions with the application, the police participants identified limitations of an online app for court evidence capture, and suggested useful redevelopments that would support police investigations, such as accessing suspects’ private social media details and generating screenshots for police reports. The academic team responded that, as required by their research project, a ‘proof of concept’ (due to be trialled in another police force) had been developed and could not be changed. Although knowledge from practice was offered, the academics were not motivated to change their research, which they regarded as already successful. They did not step outside the academic frame or incorporate this knowledge into their research.

The evaluation of this Evidence Café identified that the academic knowledge was siloed and resistant to change from practice influence, thus not allowing for two-way exchange of understanding. This resulted in the shared research evidence lacking relevance to practice needs and led to a lack of knowledge exchange and a lack of impact on practice.

During Evidence Café 12, it became apparent that the research, as designed and implemented, was not seen as relevant by the practitioners as it did not address their practical issues, so although the EBC had the power to effect change, there was no point of connection between the research and practice.

Figure 3 uses the evidence typology to show how the experiential feedback on the tool offered by participants (Column 1) did not have an impact on research (Column 4). It uses red arrows to illustrate the flow of experiential evidence from practice to academia. The research gaps identified by participants were taken by academics to feed into ideas for future research proposals, but unless authentic knowledge exchange was built into the research, the impact on practice of these future research projects may be limited.

In Case Study 1, a great deal of communication took place between practice and academia, focused on the discussion object of the app running on smartphones or iPads, but this did not result in meaning making or changed understandings. Case Study 1 is an example of an Evidence Café where knowledge exchange did not occur. It has been included to demonstrate how our understanding of the factors that contribute to an effective Evidence Café were built not only on our successful Cafés, but also on the lessons learnt from Cafés that were less successful. Evidence flow was limited, and what flow there was had little impact, as neither participants nor academics left with changed or revised understanding.

Case Study 1: Findings

Motivations: The academic motivation was to share their research with a police force, use the Evidence Café as a dissemination activity and collect ideas for future research projects. The police motivation for Evidence Café 12 was to preview cutting-edge digital forensic research to explore how this could address the practice issues faced by the digital forensics technicians and investigators attending the Café. Analysis identified that a key barrier to research uptake was a lack of academic power to effect changes (for example, the principal investigator was not present at the event). This motivation contrasted with the motivation of the academics in Case Study 2 and Case Study 3, who were seeking to integrate input from practitioners into their research. The motivation of the academics in Case Study 1 did not allow them to be responsive to the evidence offered by police participants.

Timing: This Evidence Café was run after technology development and just before evaluation procedures (which had been established); thus, the timing was late in the research cycle. The reluctance to integrate evidence from practice was partly due to the timing in the research at which the Café took place. If knowledge exchange activities are placed at the end of the research, they risk becoming dissemination activities.

Case Study 2: Evidence Café 3 – Knowledge transfer from practice to research

Evidence Café 3 was the first Café run at Police Force 3, with the process being well received by the participants. It was facilitated by an RC and EBC alongside two researching academics (including the principal investigator). The research topic for Case Study 2 was a social technology platform to enable members of the community to gather data that might be of help to the police in policing their community. The platform would also allow the police to gather data in areas of particular interest to them, such as recent criminal incidents, to which members of the community could contribute evidence. The platform was open and public.

Case Study 2: The process

The social media Evidence Café was facilitated by an RC in collaboration with an EBC from the host force and two academics who were running the research project. The discussion objects in this Café were iPads running the social platform, so that the participants could get a feel for the social platform. The participants brainstormed ideas for using the platform in a police context.

Police participants were drawn from officers and staff within the host force, many of whom had considerable experience of using social media and were keen to explore research-informed ways to improve their community engagement through social media. The police EBC was a front-line officer. Thus, the academics had the authority to support knowledge exchange, even if that exchange gave rise to changes in practice. The EBC, on the other hand, had influence, but lacked the authority to effect change within the host organization.

Case Study 2: Analysis

The police role in the whole-group discussion resulted in their identification of ethical issues (for example, identifiable actions) in public use of social media for police purposes, as well as a reluctance to change current social media practices.

The timing of this Evidence Café, run at the start of the research project, meant that academics expected participants to contribute ideas for use on the platform. They did not anticipate the barriers that were highlighted by the police that made the platform unsuitable for the police. However, the academics’ level of power within the project (one being the principal investigator), their motivation to engage the police and the timing in the research cycle resulted in this feedback being used to modify the research design. The platform went on to be developed with more community focus. However, while the police participants and EBC were enthusiastic to follow up the redesigned research project, the top-level leadership of the police force did not support further involvement. The EBC in this instance was a front-line officer with less organizational power than the EBC in Case Study 1. Figure 4 illustrates the flow of evidence from practice to research, resulting in an increase in research knowledge as academics collected and acted upon the police feedback on their research design. However, there was no matching flow of research evidence to practice. There was potential for flow of research evidence through further involvement with the redesigned project, but the EBC lacked the power to take this initiative forward.

Case Study 2: Findings

Motivation: Academics were motivated by gathering police feedback on the usefulness of the technology for policing practice and feeding this into their research process. The police motivation was to review research-informed advances to augment their existing social media practices and review the value of becoming a research partner in further activities. The inability of the EBC to get backing from their superiors, and the consequent lack of impact on the host organization, highlights the importance of decision-making power in knowledge-exchange activities. If either the academic or the host organization EBC do not have decision-making power, then the opportunity to effect change from an Evidence Café is reduced.

Timing: This Evidence Café was conducted in the early stages of the research, after the platform had been developed and used in other contexts, but before it was adapted for use with the police. This meant that the academics were better able to be open to input from practice. Timing for the host police force was less opportune, since it coincided with a change in leadership and a realignment of priorities within that specific police force away from evidence-based practice.

Case Study 3: Evidence Café 6 – Equitable knowledge exchange

Evidence Café 6 was the first Café run at Police Force 6. The process was very well received by the police force, and subsequent Evidence Cafés were requested to be held beyond the analysis period reported in this paper. Case Study 3 demonstrates two-way knowledge exchange facilitated by an RC in collaboration with three EBCs from the host force and an academic expert (principal investigator) focusing on the topic of demand management. A police officer – referred to as a senior practitioner fellow (SPF), who was seconded from operational duties to work on a research project with the support of an academic – and a PhD student also attended the Evidence Café in order to collect data for their research. The host force EBC had requested that the SPF give a short presentation to share insights on the experience of conducting police research with the support of academia.

The academic was a principal investigator with considerable experience of researching demand in the medical sector. He was motivated by a wish to extend his research into the domain of policing. The EBC was a member of police staff in a management role, tasked with improving how the force coped with demand through a series of cross-disciplinary initiatives. Police participants were front-line officers and staff.

Case Study 3: The process

The Evidence Café began with an academic presentation of research into demand categorization, presenting different ways of classifying the types of demand faced by police forces. This led into the group meaning-making activity around the discussion object, a Home Office table containing five categories of demand, by which participants were invited to classify the types of demand they experienced during their work. This was followed by whole-group discussion facilitated by the academic.

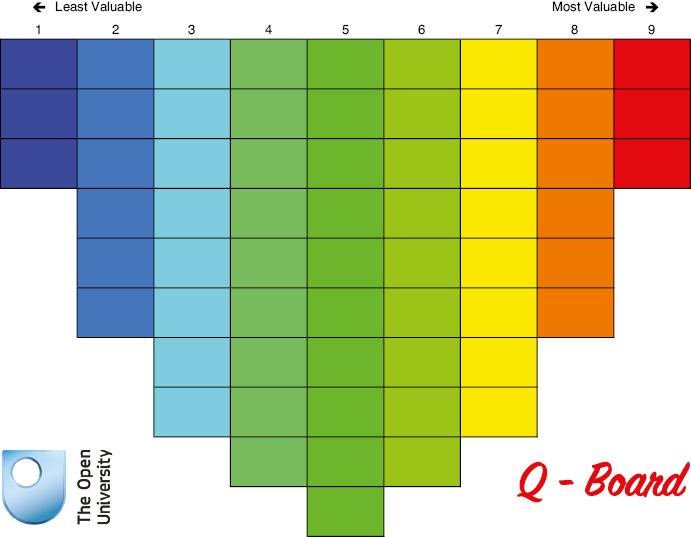

While this was taking place, the SPF collected data relevant to his own policing priorities research in an adjoining room using a Q-board methodology (Stephenson, 1953). Figure 5 shows the Q-board used.

The Q-board methodology was used to reflect on policing with limited resources, with participants given 62 tiles categorizing demands on the police (for example, parking offences, child abuse, burglary) that had been previously identified, and prioritizing them on the Q-board as more or less valuable. After the whole-group feedback session, the SPF gave a research presentation that generated great interest as it was presented from a strong police practice perspective. Seeing the level of engagement, the academic and RC opportunistically decided to redeploy the Q-board as a second discussion object. They turned it into a collaborative, reflective activity, with two groups of participants, each with a Q-board and a set of demand tiles. Each group had to come to a collective decision as to where to place each tile, with various participants voicing their views. The engaging nature of the Q-board as a discussion object helped break down barriers of status and role, and the discussions were more revealing than the ultimate placement of the tiles. For example, when handling the ‘parking offences’ tile, most participants would put this down as the least valuable. However, one participant commented, ‘But if you were to ask the Police and Crime Commissioner, he would probably place this as much more valuable, given the pressure from residents’. This was a reference to a tension between the motivation of a Police and Crime Commissioner, who is elected by members of the public, and the police who have to carry out the job, and it is relevant to the choices made about dealing with demand.

The unplanned discussion object was so engaging that participants stayed for an additional 40 minutes over the original duration of the Evidence Café in order to complete the activity. By being responsive to the participants in the room, the academic and RC were able to develop what was originally a research data collection tool into an effective discussion object that was subsequently redeployed in future Evidence Cafés on demand management with another four police forces across the UK.

Case Study 3: Analysis

Both the presentation and the interactive activities focused upon the discussion objects triggered engagement and discussion between participants about the basis for choices made in policing practice and public perceptions. The key output was not the final classification of demand types, but the meaning making that took place supporting the flow of evidence from research into practice. The participants gained a new perspective on their demand, and on successful techniques to manage policing demand. In addition, the interactive activities initiated a two-way flow of evidence between practice and research as academics learnt more about the relevance of the research for policing practice.

The flow of evidence between practice and academia, and the dialogic meaning-making processes, are represented in Figure 6. The red lines show the flow from practice to research (data to information and knowledge) through research data collection feeding into published findings (that is, facilitated Q-board research data collection in a side room – represented by the grey box). The blue lines represent data sharing and dialogic meaning making between police participants, with academics engaging with and supporting the process (purple boxes).

Case Study 3 demonstrates two-way evidence flow leading to effective knowledge exchange with impacts on both research and practice. The academic, EBC and RC (as well as the senior practitioner fellow) all emerged with changed understandings. Data collection informed research practice, with a measurable impact on academia. Police practitioners also learnt new demand classification techniques leading to new police practices at an organizational level. The police force subsequently set up multidisciplinary teams to identify different types of force demand and implement techniques to mitigate undesirable and unnecessary demand, with Evidence Café methods kicking off these initiatives.

This particular Café was the first on demand management with the police, and it demonstrates the importance of a flexible approach to facilitating evidence flow between research and practice.

Case Study 3: Findings

Motivation: Academics were motivated to develop their research from one domain (health care) into impacts within another domain (police). To achieve this goal, they also sought to capture research data and the police perspective through the Café process. The police were motivated to develop research-informed practices and experience Evidence Café methods to redeploy within their force. The Q-board was found to be valuable both to collect data in one activity and then as a discussion object in order to stimulate dialogic meaning making in another activity, facilitated by champions and researchers. This revealed the important role of discussion objects as both an equitable (discussion object) and non-equitable (data collection instrument) means of knowledge exchange. Evidence Café methods were later reused by the police to facilitate knowledge exchange and demand-management initiatives.

Timing: This Evidence Café used evidence from established research in another sector with a view to identifying productive areas for research into police demand. The Café was very early in the research process with the police. The academic was able to build on the knowledge exchange during this and subsequent Cafés, developing a research project into police demand that was relevant to practice and that was conducted in collaboration with police officers as researchers (Walley and Jennison-Phillips, 2020). The two hours of this case study contained the same proportion of presentational and collaborative activities as the other two case studies. The Home Office table of demand was an effective discussion object that generated equitable two-way evidence flow. This Evidence Café stands out because of the redeployment of a data collection instrument, the Q-board, as a discussion object at the end of the Café, thereby providing additional opportunities for dialogic meaning making and evidence flow.

Discussion

Overall, the findings revealed that the champions and discussion objects, when effectively designed and implemented, were able to overcome challenges to effective knowledge exchange. These challenges arose from competing objectives in motivations (affected by power and authority) and timings.

The Evidence Café process was analysed using an evidence typology, originally developed as a discussion object and then redeployed as a framework of analysis with thematic analysis, to highlight the evidence flow and processes in effective knowledge exchange between research and practice. The findings identified that while the Evidence Café process could support effective two-way knowledge exchange, there were barriers to ensuring a smooth and equitable flow of evidence with a measurable impact on practice and research.

The analysis identified competing objectives in motivations and timings as key challenges that, when effectively overcome, support equitable knowledge exchange for all evidence bases. In particular, for two-way and equitable knowledge exchange between practice and research to occur, we need to support a collaborative meaning-making process for all through two key processes:

-

champions (EBCs and RCs), who facilitate the use of

-

discussion objects for complementary evidence bases.

Enablers: Champions and discussion objects

The role of the practice-based EBCs and academic-based RCs was key to the success of the knowledge exchange. Not only did they ensure co-design of the event and facilitate equitable group work around discussion objects, but they also highlighted the relevance of research to police practice and reshaped research objectives to increase relevance. All Evidence Cafés were jointly introduced by the EBC and RC, and in some, the EBC also gave a presentation about their experiences crossing boundaries between research and practice. This supported meaning making by contextualizing research evidence in practice, and by highlighting connections between the world of policing and the world of academic research. In this sense, the EBCs and RCs acted as a bridge or ‘boundary creature’ (Adams et al., 2013) between the domains of policing and academia.

Research has highlighted that it is not only people that can cross boundaries; objects also facilitate crossing the research and practice boundaries. Boundary objects have been identified as holding an important role as a connection point and a way of mediating evidence, allowing people from differing domains to develop new and shared perspectives. These objects can become embedded in contextual norms, and jargon risks acting as a barrier to traversing contexts. However, when effectively designed, they can support developing new or negotiated joint understanding between people from different worlds who undertake collaborative tasks related to evidence boundary objects (Carlile, 2002; Sapsed and Salter, 2004; Scarbrough et al., 2015; Star, 2010; Star and Griesemer, 1989).

In Evidence Cafés, we developed and reviewed a specific type of boundary object in the form of discussion objects. Boundary objects can facilitate one-way exchange across boundaries asynchronously as well as synchronously. Discussion objects specifically enable equitable co-creation in synchronous evidence exchange. The discussion objects helped practitioners to visualize academic research findings in terms that were relevant to their practice, acting as a bridge between academia and practice across which academics and practitioners could meet on equal terms to realize a shared understanding. Once research was contextualized, practitioners were better able to offer their perspectives and evidence. Thus, discussion objects acted both as a way of making research more accessible, and as a channel through which practice-informed views and evidence from practitioners could contribute to academic research.

The important characteristic of an Evidence Café discussion object, facilitated by the champions, is that it promotes meaningful two-way dialogue among the participants and between the participants and the academic(s). This engages participants who are interested in the topic, as well as breaking down barriers of rank and status, and enabling participants, essentially, to forget the constraints they usually work under and contribute and listen freely and constructively.

Challenges: Competing objectives in motivation and timing

Motivation is a key cause of tension and competing objectives between practice-based and academic research, with practice-based research placing more weight on notions of evidence validity, and academic research assigning importance to evidence rigour and reflexive processes. While both practice-based and academic research are valid, it is often perceived, in both domains, that rigorous academic research evidence is superior and should therefore have more power. To be effective, an Evidence Café needs to give equal weight to both evidence bases. In the weeks running up to each Café, it was important for the RC and EBC to address this tension by matching the objectives of the host organization to those of the academics. Matching objectives does not mean having the same objectives, but rather having objectives that complement each other.

The level of power or authority of champions, academics and participants within both types of organization was identified as important in facilitating motivation to overcome the challenges of competing objectives. For example, within the police, the status of the EBC was a key factor influencing the extent to which evidence and meaning making from the Evidence Café could be successfully integrated with practice. In Case Study 3, the police EBC was a member of police staff with the remit and authority to set up initiatives to address issues of excessive demand, and therefore the impact on practice from Case Study 3 was significant. In Case Study 2, the EBC was a police constable in a force where the leadership team were resetting priorities away from evidence-based practice, thus the impact on practice was limited. The EBC in Case Study 1 was an officer of rank with the authority to drive forward evidence-based practice initiatives, and did so by reusing Evidence Café methods to run Practitioner Cafés within the force. EBCs are key in ensuring sustainable impact on practice from Evidence Cafés, but this cannot be achieved without buy-in and support from their organization and leadership team.

From an academic perspective, the challenges of power on motivations were more subtle but still evident. In Case Study 1, the research champions were academic researchers working on a project overseen and coordinated by a principal investigator who did not attend the Evidence Café. The power they had to initiate technical changes without the principal investigator’s oversight was limited. However, in Case Studies 2 and 3, the academics were both leading and researching on the project, allowing for deeper insights to be taken from and adapted into the research project itself.

Competing objectives of what is considered important or irrelevant evidence can affect motivations in applying the evidence to practice. Evidence Cafés highlight that evidence from both research and practice is of value, but it can be challenging for academia to integrate the two types of evidence without giving more weight to evidence obtained through recognized academic research in preference to rich experiential or procedural evidence developed and shared by practitioners, as illustrated in Case Study 1, where the academics were motivated by disseminating their research. This again highlights the importance of contrasting and competing Evidence Café objectives between the practitioners and academics. For example, within research, if academics have an objective it can blind them to adapting to feedback from practice evidence. In reality, they have the power to change, but the reluctance is more about their motivation to change. Effective research is more about appropriate objectives than about power. In contrast, within practice, the key lies more with power than objectives, as illustrated in Case Study 2, where the EBC lacked the rank and power to effect change. The findings from these Evidence Cafés have identified that with practitioners it is about getting the right people in the room – those with the authority to initiate and carry through change. Within the practical application of any research, it is about changing mindsets, and thus the relevance of the research to practice.

Finally, these Evidence Café findings identified the importance of timing for the Evidence Cafés. The challenge here came in fitting with the research process to enable academics to benefit from practitioner insights. There was also a timing challenge of enabling practitioners to develop a deeper understanding of how current practices may be adapted to align with, and benefit from, new research innovations. Balancing these challenges provides further competing motivations that an EBC and RC need to negotiate and find complementary timings for Evidence Cafés.

Academics are accustomed to presenting their completed research to an audience in a formal setting, at the end of a project. Some academics initially viewed Evidence Cafés as a dissemination activity, to be plugged in at the end of the research to tick a ‘public engagement’ check-box. For example, Case Study 1 highlighted that timing an Evidence Café late in the research cycle is unproductive as it necessarily frames the Café as a dissemination activity. There was no time or space in the Evidence Café process to integrate the evidence flowing from practice into valuable changes for the research project. Thus, although there was potential for knowledge exchange from which both research and practice could benefit, that potential was not realized. This highlights the importance of academics recognizing how an Evidence Café, as an equitable knowledge exchange process, should take place early in the research process. An example of an Evidence Café set at the start of the research design process was Case Study 2, and as such the academics were able to benefit from evidence flowing from practice into research. However, there should also be equity in the timings to benefit practice and the appropriate application of research. Case Study 2 did not effectively balance with competing practice timings to fit with a need for change in the practice context, thus allowing impact upon practice as well as research. While effective balancing of competing motivations in Evidence Café timings are important, this does not mean that all Evidence Cafés placed at the end of a research project will become dissemination activities. Our research highlighted that this very much depends upon the role of the EBCs, RCs and academics, the nature of the research, and how adaptable to changes all of these are. For example, Case Study 3 is an exemplar for many other successful Evidence Cafés that managed to balance competing objectives and timings for both research and practice. This Evidence Café was the first of a series of six Cafés about demand held at different points in the research cycle, within different police forces meeting their own specific practice needs. Part of the research had been fully developed (that is, demand management categorizations) and part was at the start of the research process. All the EBCs and RCs were open to adaptive change to benefit all participants and impact both on research and practice. As such, Case Study 3 is a good example of many other Evidence Cafés that have helped frame appropriate research.

Conclusions

Effective knowledge exchange benefits from good-quality evidence that is research and practice based, combined to result in sustainable, significant and scalable impact for both practice and research. However, barriers can arise due to issues around conflicting motivations from practice and academia, including the impacts of power and authority to effect change, as well as the timing of the Evidence Café. In particular the concept of ‘knowledge’ in knowledge exchange has been hijacked by the use of research evidence being translated into practice contexts. We conclude that there is the need to reframe knowledge exchange through the lens of ‘evidence’, both practice-based and academically based, analysed at different levels (from data to knowledge) and framed on a continuum of rigour (from experience to research). This lens applied through Evidence Cafés allows us to equitably co-create new meanings that are applicable and impactful for both academic and practice contexts.

In Figure 2, we see that using the evidence lens through Evidence Cafés, while not ensuring all knowledge exchange is equitable, does shift the perspective more towards equitable evidence flow. While Case Study 1 was an example of ‘what not to do’, Case Study 2 presented an example of elements of evidence flow. However, although the event resulted in reframing the research, poor impacts were realized upon practice. This was due to a change in strategic priorities at the host police force, with the EBC lacking the authority to effect changes. While this was not an ideal example of evidence flow, it does highlight the need to develop research with practice needs in mind. In particular, it highlights the value of forms of evidence and expertise coordinated by champions from both contexts who can frame the event as a co-creation process. For example, Case Study 3 (the Evidence Café on demand management) illustrates two-way evidence flow. This case study represents the gold standard for Evidence Cafés, demonstrating equitable knowledge exchange with impacts on both research and practice. During the Café, police practitioners explored new techniques to classify demand and identify undesirable demand from the research, and they co-created ideas on how to address this through dialogue, framed by the discussion objects. This process then resulted in impacts upon police practices. For example, the research findings and demand classifications were adopted by the host police force, who subsequently set up multidisciplinary teams to identify different types of demand elsewhere in the force with a view to implementing techniques to mitigate undesirable and unnecessary demand. The host force also adopted the Evidence Café methods of equitable knowledge exchange, initiating the work of these cross-disciplinary policing teams with Evidence Café events. Thus, the police benefited from the new perspectives on demand management, integrating these new perspectives into their practice through new initiatives.

This Evidence Café also showcases impacts on academic research. For example, the completed demand categories tables (discussion object 1), together with video and participant observation notes on the dialogues around the Q-board (discussion object 2), were used by the academic expert on demand to extend his public-sector research into the policing context. Also, the two data collection sessions conducted opportunistically as part of the Evidence Café by practitioners and PhD students provided data for their own research.

Finally, the three case studies show how processes that can trigger and support two-way evidence flow leading to equitable knowledge exchange can also act as barriers to knowledge exchange when not applied correctly. This paper therefore presents a frame for an evidence lens in knowledge exchange, and a framework for an Evidence Café quality standard that will feed into future work to identify training and support needs for evidence-based champions. Alongside this, training will be developed to guide academics in the processes of facilitating effective evidence flow and demonstrate how to use these processes to produce engaged research that leads to both equitable knowledge exchange and sustainable impact.

Notes on the contributors

Gill Clough is a research fellow with the Open University. She has worked on large-scale international research projects in technology-enhanced learning (for example, the €2.1m EU Juxtalearn project (http://juxtalearn.eu) and the €3.2m EU xDelia project (http://www.xdelia.org/)), and more recently on knowledge exchange and professional development with the Centre for Policing Research and Learning (http://centre-for-policing.open.ac.uk/).

Anne Adams is Open University Professional Development Director and was Director for Knowledge Exchange in the national Centre for Policing Research and Learning. She has a large publications and large-scale international research portfolio producing extensive collaborative interdisciplinary research and knowledge exchange experience (for example, Microsoft, BT, Canon, Google, NHS) producing award-winning outputs (for example, the WISE Award presented by HRH The Princess Royal).

References

Adams, A. Clough, G. FitzGerald, E. 2018a Police Knowledge Exchange: Full report 2018 Milton Keynes Open University Online. http://oro.open.ac.uk/56100/ (accessed 3 June 2020)http://oro.open.ac.uk/56100/

Adams, A. Clough, G. FitzGerald, E. 2018b Police Knowledge Exchange: Summary report Milton Keynes Open University Online. http://oro.open.ac.uk/56099/ (accessed 3 June 2020)http://oro.open.ac.uk/56099/

Adams, A. Cox, A.L. 2008 ‘Questionnaires, in-depth interviews and focus groups’ Cairns, P. Cox, A.L. Research Methods for Human–Computer Interaction Cambridge Cambridge University Press 17 34

Adams, A. Fitzgerald, E. Priestnall, G. 2013 ‘Of catwalk technologies and boundary creatures’ ACM Transactions on Computer–Human Interaction 20 3 Online http://doi.org/10.1145/2491500.2491503

Carlile, P.R. 2002 ‘A pragmatic view of knowledge and boundaries: Boundary objects in new product development’ Organization Science 13 4 442 55 Online http://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.13.4.442.2953

Corbin, J. Strauss, A. 2015 Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA SAGE Publications

Drennon, C. 2002 ‘Negotiating power and politics in practitioner inquiry communities’ New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 95 61 72 Online http://doi.org/10.1002/ace.69

Grand, A. 2015 ‘Café Scientifique’ Gunstone, R. Encyclopedia of Science Education Springer Dordrecht Online (accessed 24 June 2020) http://doi.org/10.1007%2F978-94-007-2150-0_290

Hall, B.L. Tandon, R. 2017 ‘Decolonization of knowledge, epistemicide, participatory research and higher education’ Research for All 1 1 6 19 Online http://doi.org/10.18546/RFA.01.1.02

HEFCE (Higher Education Funding Council for England) 2015 Research Excellence Framework 2014: The results REF 01.2014. Bristol: HEFCE. Online. https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/pubs/201401/ (accessed 3 June 2020)https://www.ref.ac.uk/2014/pubs/201401/

Henwood, K.L. Pidgeon, N.F. 1992 ‘Qualitative research and psychological theorizing’ British Journal of Psychology 83 1 97 111 Online http://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02426.x

Horner, R.H. Carr, E.G. Halle, J. McGee, G. Odom, S. Wolery, M. 2005 ‘The use of single-subject research to identify evidence-based practice in special education’ Exceptional Children 71 2 165 79 Online http://doi.org/10.1177/001440290507100203

Kitson, A. Harvey, G. McCormack, B. 1998 ‘Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: A conceptual framework’ Quality in Healthcare 7 3 149 58 Online http://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.7.3.149

Lum, C. 2014 ‘Policing at a crossroads’ Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 8 1 1 4 Online http://doi.org/10.1093/police/pau008

McKibbon, K.A. 1998 ‘Evidence-based practice’ Bulletin of the Medical Library Association 86 3 396 401

Rice, R.E. 2007 ‘From Athens and Berlin to LA: Faculty scholarship and the changing academy’ Perry, R.P. Smart, J.C. The Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: An evidence-based perspective Dordrecht Springer 11 21

Sapsed, J. Salter, A. 2004 ‘Postcards from the edge: Local communities, global programs and boundary objects’ Organization Studies 25 9 1515 34 Online http://doi.org/10.1177/0170840604047998

Scarbrough, H. Panourgias, N.S. Nandhakumar, J. 2015 ‘Developing a relational view of the organizing role of objects: A study of the innovation process in computer games’ Organization Studies 36 2 197 220 Online http://doi.org/10.1177/0170840614557213

Sherman, L.W. Strang, H. 2004 ‘Verdicts or inventions? Interpreting results from randomized controlled trials in criminology’ American Behavioral Scientist 47 5 575 607 Online http://doi.org/10.1177/0002764203259294

Sherman, L.W. Strang, H. Angel, C. Woods, D. Barnes, G.C. Bennett, S. Inkpen, N. 2005 ‘Effects of face-to-face restorative justice on victims of crime in four randomized, controlled trials’ Journal of Experimental Criminology 1 3 367 95 Online http://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-005-8126-y

Star, S.L. 2010 ‘This is not a boundary object: Reflections on the origin of a concept’ Science, Technology, and Human Values 35 5 601 17 Online http://doi.org/10.1177/0162243910377624

Star, S.L. Griesemer, J.R. 1989 ‘Institutional ecology, “translations” and boundary objects: Amateurs and professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39’ Social Studies of Science 19 3 387 420 Online http://doi.org/10.1177/030631289019003001

Stephenson, W. 1953 The Study of Behavior: Q-technique and its methodology Chicago University of Chicago Press

Walley, P. Jennison-Phillips, A. 2020 ‘A study of non-urgent demand to identify opportunities for demand reduction’ Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice 14 2 542 54 Online http://doi.org/10.1093/police/pay034