Introduction

Much Irish studies scholarship, especially since the mid-1990s, has acknowledged the central position of the Great Irish Famine (1845–50) in Irish and Irish-diasporic history, cultural memory and identity. The Famine was caused by an unknown fungus which struck the potato crop repeatedly. Because a large part of the Irish population was (almost) fully dependent on the potato and did not have sufficient access to alternative means to procure food, the Famine’s demographic results were extreme. Estimates vary, but between 1845 and 1855, out of a population of over 8 million, about 1 million died because of malnutrition and famine-related diseases, and another 1.8 million emigrated (Kenny, 2000; Ó Gráda, 1999).

As Ireland was still part of the United Kingdom at the time, the crisis has also been considered in a colonial context. Analyses from this perspective focus on the role and responsibilities of British and Anglo-Irish landlords, and especially on the response of the colonial British government to the Famine. Government policy and culpability have long been points of contention, and their consideration informed nationalist and Irish historiographic discourse from early on. The latter becomes clear from the writings of exiled Irish nationalist, journalist and popular historian John Mitchel (1871: 152), who famously stated that ‘The Almighty, indeed, sent the potato blight, but the English created the famine.’ Today, interpretations of the Famine vary widely: it has been interpreted relatively straightforwardly as a period of mass starvation and disease, and in more complex fashion as a cultural trauma, a diasporic origin myth, a colonial catastrophe or even, inspired by Mitchel’s (1871) rhetoric, as a genocide. Cormac Ó Gráda (2001) rejects the term ‘cultural trauma’, and Oona Frawley (2014) critically assesses the validity of the term. David Lloyd (2000: 221) favours the label ‘colonial catastrophe’. I (Janssen, 2018) critically reassess the concepts of origin myth and victim diaspora. Popular historian Tim Pat Coogan (2012) claims that the Famine was an act of genocide. Several scholars have responded critically to this, including Mark McGowan (2017).

Clearly, the period continues to spark scholarly and public debates, emphasising its status as a ‘contested past’ (Terra, 2014: 227) or ‘controversial issue’, an issue about which ‘contrary views can be held … while both views are rational’ (Dearden, 1981, as cited in Goldberg and Savenije, 2018: 503). Taking this contested position as its point of departure, this article investigates the representation and narrativisation of the Famine in recent history textbooks for the secondary level published in Ireland and the UK (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland). Irish primary-level history textbooks also discuss the Famine, but they are not matched by UK textbooks in this; hence, this article’s comparative approach is limited to the secondary level. The article considers textbooks because they are key in passing on historical awareness to students (Van Berkel, 2017), and ‘have … been seen to act as a condensed version of the society that produced them’ (Fischer, 2000, as cited in Mac Gearailt, 2018: 233–4). Textbooks are often considered as ‘mirroring dominant content and practices’ (Repoussi and Tutiaux-Guillon, 2010: 2), and are said to ‘contain an expression of the self-image of the nation-state’ and to function as tools to interpellate students into a communal identity (Fuchs and Otto, 2013: 3).

The Famine is part of national, colonial, European and diasporic narratives; such different scales of spatial and historical embedding inflect the ways in which the crisis is remembered and contextualised. In the UK and Ireland, historical contextualisation and perspective taking are considered key to the skillset to be developed by students when studying history. A thorough grasp of these skills becomes even more important when dealing with controversial historical issues. As such, historical contextualisation and historical perspective taking are key to the analysis offered (Bartelds et al., 2020; Endacott and Brooks, 2018).

When analysing the multiple and potentially contesting interpretations of the Great Irish Famine, existing scholarship by historians such as Cormac Ó Gráda (1999, 2001, 2015), Mark McGowan (2017) and Peter Gray (1995, 2013) has focused on several key contested elements which can be linked directly to considerations of causation and responsibility for the Famine and its magnitude. I include references to the work of these historians throughout this article. Additionally, in his accessible introductory essay to The Irish Famine, Colm Tóibín (2004) concisely explains the contested issues which have long fed into divergent views on the Famine. The key contested elements are: food imports and exports during the crisis; the British government’s laissez-faire economic policy in relation to aid provision; providentialist interpretations – the Famine as divine punishment; and victim–perpetrator discourses. These crucial factors complicate any unilateral interpretation of the Great Famine, and they are the focus of the analysis provided below.

The research for this article is part of Heritages of Hunger, a project which comparatively considers the legacies of historical periods of hunger in Europe, and which seeks to stimulate transnational understanding through education ( https://www.ru.nl/heritagesofhunger). As a scholar specialising in Famine memory, I consider the position of representations of the Famine in their broader memory cultures. The current article, then, is in no way intended as a value judgement on the typically rich history textbooks analysed below. Rather, my specific purpose is to consider textbook representations of the Irish Famine from the joint concepts of contested pasts, historical contextualisation and perspective taking.

While often intended to foster inclusion, cohesion and social purpose, history education can also shape differences and ‘strengthen negative perceptions of outgroups’ (Korostelina, 2013: 2, 17). Not understanding the full historical context, or not having an awareness of the various perspectives involved for a controversial issue such as the Famine, might sustain lingering historical differences. The linked questions central to this research, then, are: How do recent secondary-level history textbooks from Ireland and the UK represent these key contested elements regarding the Great Irish Famine? Do they provide sufficiently complex accounts, thereby facilitating historical contextualisation and perspective taking? The article engages with these questions from a comparative perspective.

Existing research: history textbooks 1900–2010

Previous studies on the Famine in Irish and UK history textbooks have also investigated the representation of the key contested issues listed above. This shows that these have not only long formed part of the narrative repertoire of Famine history, but also of its textbook history more specifically; therefore, they are validated as an analytic framework for the current study.

The aforementioned interpretation provided by Mitchel (1871) has long held staying power, and, partly due to the ‘relative paucity of scholarly work on the Famine’ prior to the late twentieth century, it also found its way into Irish history textbooks (Boylan, 2017: 65). Nevertheless, already between 1900 and Irish independence, textbooks ‘eschewed’ the outlier of this rhetoric, which considered the ‘Famine as a deliberate act of extermination’ (Boylan, 2017: 59). During this period, the Commissioners of National Education in Ireland endorsed a non-partisan approach to history, and textbooks offered diverse interpretations. Between 1922 and 1971, Irish textbooks became more partisan (Boylan, 2017). Jan Germen Janmaat (2012) has found that discussions of the Famine in Irish history textbooks after independence were moderately nationalist, and that in the 1960s, a shift to more balanced accounts took place.

Janmaat (2012: 88) investigates the period 1922–97 and finds that already during its early decades, Irish textbooks did not uniformly give landlords an ethnic label, nor were landlords ‘unilaterally dismissed as ruthless exploiters’. As I will demonstrate, my sample does show more simplification with regard to landlords. This suggests that recent textbook narratives build upon the narrative provided by the Irish textbooks from the period 1922–71 studied by Ciara Boylan (2017: 63), which ‘often presented a simplified “villains” and “victims” narrative’. Boylan (2017: 63) also includes that in textbooks used in Irish National Schools, the Famine was incorporated into a historical narrative which ‘stressed Ireland’s triumph over adversity’, and which provided ‘a justification for the struggle for political independence’.

Ann Doyle (2002) has researched English textbooks from the 1920s until the early 2000s, and finds that ethnocentrism, stereotyping, prejudice, simplification and omission colour discussions of the Famine throughout the period. Although these potential distortions are significantly reduced in more recent books, Doyle (2002) signals their continued presence. Luke Terra (2014) investigates books used in Northern Irish schools between 1968 and 2010; he points out that in Northern Ireland, the Famine is a politically sensitive event, and he discusses the impossibility of providing a national account of the period. Terra’s (2014) Northern Irish sample shows a transition from coherent to contestable narratives, and he finds that textbooks published between 2007 and 2009 offer the most nuanced and multiperspectival treatment of the Famine.

Sources

Table 1 and Table 2 list the textbooks considered for this study. I have analysed a substantial sample of textbooks (15 for the UK; 12 for Ireland) published between 2010 and 2020, and which include the Great Irish Famine. The sample is representative of contemporary trends in textbook content about the Famine, and it contains publications following recent history curriculum revisions – including the phased transition into the Irish Junior Cycle programme from 2014 (NCCA, n.d.) and the revision to the English National Curriculum, which has also been in operation since 2014 (Chapman, 2021) – as well as slightly older textbooks created for previous curricula which could still be used in teaching during this period.

Although realising that teachers have access to many educational materials beyond the book, this article focuses on textbooks. The number of non-textbook sources is substantial, and not every book or teacher makes similar use of such sources. Limiting the analysis to the content offered by the textbooks ensures a comparative approach which is on equal footing and covers a clearly delimited and balanced corpus, focused on the same type of medium. Many, although certainly not all, additional sources also lack the authority still accorded to history textbooks. While the publication of teaching materials is not regulated by the state in Ireland or the UK, national curricula do inform the content offered in educational textbooks; this alignment is often included as a selling point in educational publishers’ blurbs. Moreover, history textbooks, especially more ‘traditional’ examples, offer (the suggestion of) cohesive narratives (Klerides, 2010).

UK history textbooks consulted for this study (Source: Author, 2023)

| Author(s) | Title | Publisher | Year | Level | Space for Great Irish Famine* | Orien- tation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| John D. Clare, Neil Bates, Alec Fisher and Richard Kennett | Making Sense of History, 1845–1901 | Hodder Education | 2015 | KS3 Years 7–9 ages 11–14 |

chpt. | UK |

| Robert Peal | Knowing History: KS3 History Modern Britain 1760–1900 | HarperCollins | 2017 | KS3 Years 7–9 ages 11–14 |

section in chpt. | UK |

| Aaron Wilkes | KS3 History – Industry, Invention and Empire: Britain 1745–1901 | Oxford | 2014 | KS3 Years 7–9 ages 11–14 |

2 sections in chpt. | UK |

| Aaron Wilkes | KS3 History – Revolution, Industry and Empire: Britain 1558–1901 | Oxford | 2020 | KS3 Years 7–9 ages 11–14 |

section in chpt. | UK |

| Lindsay Bruce, J.A. Cloake, Kevin Newman and Aaron Wilkes | Thematic Studies c790–Present Day | Oxford | 2016 | KS4 Years 10–11 ages 15–16 |

2 short subsections in 2 chpts | UK |

| Paul Adelman and Mike Byrne | Access to History: Great Britain and the Irish question 1774–1923 | Hodder Education | 2016 | AS/A level ages 16–18 |

chpt. | UK |

| Benjamin Armstrong | Access to History: Britain 1783–1885 | Hodder Education | 2020 | AS/A level ages 16–18 |

mentions | UK |

| Mike Byrne and Nick Shepley | AQA A-level History: Britain 1851–1964: Challenge and transformation | Hodder | 2015 | AS/A level ages 16–18 |

mentions | UK |

| Ailsa Fortune | Oxford AQA History: Challenge and transformation: Britain c1851–1964 | Oxford | 2016 | AS/A level ages 16–18 |

short subsection in chpt. | UK |

| Maxine Hughes, Chris Hume and Holly Robertson | National 4 & 5 History Course Notes | Leckie/Collins | 2018 | Senior Phase ages 15–16 |

mention in chpt. | Scotland |

| Adam Kidson | Edexcel A Level History. Paper 3: Ireland and the Union, c1774–1923 | Pearson | 2016 | AS/A level ages 16–18 |

chpt. and frequent mentions throughout book | UK |

| Russell Rees | Ireland under the Union 1800–1900 | Colourprint Educational | 2018 | A2 level ages 17–18 |

2 sections in 2 chpts; many mentions throughout book | Northern Ireland |

| Alan Todd and Jean Bottaro | History for the IB Diploma Paper 2: Independence Movements (1800–2000) | Cambridge University Press | 2015 | IB Diploma ages 16–19 |

substantial subsection in chpt. | UK |

| Mike Wells and Mary Dicken | OCR A Level History: Britain 1846–1951 | Hodder | 2015 | AS/A level ages 16–18 |

subsection in chpt.; some mentions | UK |

| Simon Wood and Claire Wood | National 4 & 5 History: Migration and Empire 1830–1939 (2nd ed.) | Hodder Gibson | 2018 | Senior Phase ages 15–16 |

section in chpt. | Scotland |

-

*Note: The terms ‘unit’ and ‘chapter’ have been standardised to ‘chpt’.

Irish history textbooks consulted for this study (Source: Author, 2023)

| Author(s) | Title | Publisher | Year | Level | Space for Great Irish Famine* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Máire de Buitléir, Gráinne Henry, Tim Nyhan and Stephen Tonge | Timeline: A complete history text for Junior Certificate History | Edco | 2014 | Junior ages 12–16 |

chpt. |

| Seán Delap and Paul McCormack | Time Bound | Folens | 2018 | Junior ages 12–16 |

chpt.; mention in other chpt. |

| Seán Delap and Paul McCormack | Uncovering History | Folens | 2011 | Junior ages 12–16 |

chpt.; mention in other chpt. |

| Gráinne Henry, Bairbre Kennedy, Tim Nyhan and Stephen Tonge | History Alive | Edco | 2018 | Junior ages 12–16 |

chpt. |

| Dermot Lucey (Skills Book: Stacey Stout with Lucey) | Making History: Complete Junior Cycle History | Gill Education | 2018 | Junior ages 12–16 |

chpt.; mention in other chpt. |

| Patricia McCarthy | Junior Certificate History. Footsteps in Time 1 | CJ Fallon | 2010 | Junior ages 12–16 |

chpt. |

| Patsy McCaughey | Discovering History: New Junior Cycle History | Mentor Books | 2018 | Junior ages 12–16 |

chpt. |

| Gregg O’Neill and Eimear Jenkinson | Artefact | Educate.ie | 2018 | Junior ages 12–16 |

chpt. |

| Dan Sheedy | History in Focus 1: A history of Ireland for the Junior Cycle | CJ Fallon | 2018 | Junior ages 12–16 |

chpt. |

| Gerard Brockie and Raymond Walsh | Modern Ireland (3rd ed.) | Gill Education | 2016 | Senior ages 5–18 |

mentions |

| Gerard Brockie and Raymond Walsh | Modern Ireland (4th ed.) | Gill Education | 2020 | Senior ages 5–18 |

mentions |

| Paul Twomey | The Making of Ireland | Educate.ie | 2016 | Senior ages 5–18 |

mentions |

-

*Note: The terms ‘unit’ and ‘chapter’ have been standardised to ‘chpt’.

Methodology and key analytic concepts

Methods

The selection of key contested topics was done a priori, on the basis of existing history and textbook scholarship on the Famine. I analysed the textbooks using narrative and content analysis. The latter refers to the coverage of people, events and motives, while the former allows for the investigation of perspectives in which such elements are represented, and how they are combined into a coherent narrative (Krippendorf, 2004; Repoussi and Tutiaux-Guillon, 2010; Terra, 2014). In the following analysis, simplification is also considered as a form of narrativisation. While the analysis conducted for this study is predominantly qualitative, at several points I provide quantitative support to indicate the frequency of a signalled narrative structure or feature.

Analytic concepts

This article combines insights from educational and textbook studies, Irish studies and cultural memory studies. Christopher Morash (1995: 2–3) argues that ‘There is no single, clear consensus as to what constituted the Famine’; what we know of the Famine today is ‘primarily a retrospective textual creation’. Analysing the textual creation of Ireland’s Famine past in school textbooks, this article considers how the crisis is narrativised, using familiar narrative formats and imagery (Wertsch, 2002).

Many scholarly, educational and popular narratives of the Famine have relied on clear victim–perpetrator discourses, where the Irish fill the former role and the British the latter. However, there are few historical situations in which such easy typecasting accords with reality; this is no different for the Irish Famine. Historians Breandán Mac Suibhne (2013) and Cormac Ó Gráda (2015) discuss the absence of peer solidarity, as well as the moral transgressions that Irish people sometimes committed to save themselves during the Famine, thereby complicating the category of victimhood. Memory scholar Michael Rothberg (2019: 1) introduces the concept of ‘implicated subject’ as an addition to ‘victims’ and ‘perpetrators’, and explains that ‘implicated subjects occupy positions of power and privilege without being themselves direct agents of harm; they contribute to, inhabit, inherit, or benefit from regimes of domination but do not originate or control such regimes’. While Rothberg (2019) focuses on how memories of violent histories inflect the present, the term ‘implicated subject’ is also useful to more adequately qualify the various roles that British and Irish individuals took on during the Famine.

A full understanding of historical morality and responsibility requires that a student is able to consider multiple historical perspectives and has a detailed grasp of historical context. Historical contextualisation here refers to ‘a temporal sense of difference’ (Endacott, 2014: 5) and ‘the ability to situate historical phenomena or the actions of historical actors in a temporal, spatial, and social context to describe, explain, compare, or evaluate them’ (Bartelds et al., 2020: 530). Through perspective taking, one shows ‘understanding of another’s prior lived experience, principles, positions, attitudes, and beliefs in order to understand how that person might have thought about the situation in question’ (Endacott and Brooks, 2018: 209). Together, historical contextualisation and perspective taking contribute to the formation of historical empathy in students (Endacott and Brooks, 2018). The latter can be defined as the ‘gaining of an understanding of how and why historical agents acted as they did’ (Van Berkel, 2017: 22; see also Bartelds et al., 2020; Endacott, 2014; Endacott and Brooks, 2018). Additionally, Keith Barton and Linda Levstik (2004: 11) write that the term pertains both to the ‘rational examination of the perspectives of people in the past’ and to the stimulation of ‘caring and commitment’. Barton and Levstik’s (2004) definition demonstrates that, for some scholars, historical empathy also encompasses an affective connection (Endacott, 2014); I have left this out of the analysis, as this takes place outside of the textbook. While sympathy suggests compassion on the basis of similarity to the self, empathy involves cognitive and affective understanding of an other (Assmann and Detmers, 2016).

The term ‘historical empathy’ is absent from the National Curriculum in England (DfE, 2014a), but the ‘History GCSE subject content’ (the General Certificate of Secondary Education, taken by 15- and 16-year-olds) does include that the specification ‘should enable students to … develop an awareness of why people, events and developments have been accorded historical significance and how and why different interpretations have been constructed about them’ (DfE, 2014b: 3). The Irish secondary history curriculum includes the term ‘empathy’, and the ‘Junior Cycle history specification’, which covers the first three years of secondary education, defines empathy as ‘Understanding the motivations, actions, values and beliefs of human beings in the context of the time in which they lived’ (Government of Ireland et al., 2017: 26). Moreover, it explicitly mentions the concept ‘Historical consciousness’: ‘Seeing the world historically, informed by an awareness of historical concepts, showing awareness of “big picture” and of time and place’ (Government of Ireland et al., 2017: 26). Such descriptions accord perspective recognition and historical context a central position (Barton and Levstik, 2004). Many textbooks also include their own definitions of these terms, which largely align with state-endorsed definitions.

Findings and discussion

Coverage of the Famine in Irish and UK textbooks, 2010–20

In 2002, Doyle registered her surprise at the ‘paucity of coverage’ concerning the Famine in English history textbooks published between the 1920s and the early 2000s (Doyle, 2002: 327). As Table 1 and Table 2 show, generally speaking, recent Irish textbooks reserve more space for the Famine than do their UK counterparts. Most Irish textbooks include a chapter on the Famine, except for Brockie and Walsh (2016, 2020) and Twomey (2016), books which are for the senior level. In textbooks geared to the UK, almost the reverse is the case: only Rees (2018), Adelman and Byrne (2016) and Kidson (2016) devote equally substantial textual space to the topic. These titles are also geared to advanced levels, and they cover Ireland or British–Irish relations specifically.

Lengthier discussions of the Famine in Irish junior-level and UK senior-level textbooks can be explained by the curricular placement of the Famine. In Ireland, it forms part of the national history strand of the National Curriculum for the junior level (Government of Ireland et al., 2017). At this level, history is still a mandatory subject, so here the inclusion of the Famine will have a larger societal impact. For the Welsh GCSE, it is a small part of the optional breadth study topic ‘Changes in patterns of migration, c. 1500 to the present day’ (WJEC, 2016: 27–9). The Famine is not included in the Northern Irish GCSE specification in history (CCEA, 2017), but it does feature in the senior-level GCE specification (CCEA, 2019). The National Curriculum in England includes the non-statutory example of ‘Ireland and Home Rule’, but it does not explicitly mention the Famine (DfE, 2014a: 96). For the Scottish higher levels, ‘Immigration to Scotland 1830s–1939’ includes Irish immigration, but the Famine is not explicitly mentioned (SQA, 2019, 2021).

The general narrative outline of the Famine is largely similar in the textbooks analysed for this research, aligning with the brief historical sketch provided in the introduction to this article. More specifically, in the Irish context, the Famine is placed within several of the following larger narratives: repeated famines, colonial subjugation, transformations in agriculture, emigration and the Irish diaspora, language decline, the Industrial Revolution, the post-Famine devotional revolution, and/or the struggles for independence and land ownership rights. In the UK context, it is furthermore placed in a colonial narrative, but considered from the opposite perspective; it is also included in the context of immigration to Great Britain and the repeal of the Corn Laws.

Imports and exports, laissez-faire and providentialism

The British government’s ideology and concomitant decision making during the Famine are notoriously hard to understand from a present-day perspective, as they were strongly influenced by the since discredited principles of laissez-faire and providentialism. (See Gray [1995, 2013, for example] on political, economic and religious government ideology during the Famine.) While the latter ‘lay at the heart of indifference for some Evangelicals’ and government officials during the Famine (McGowan, 2017: 97), it is only infrequently included in textbooks. Two Irish and two UK textbooks mention providentialism, which also demonstrates that geographic orientation does not influence the inclusion or exclusion of this religious dimension. Only Rees (2018) uses the term ‘providentialism’ explicitly; Kidson (2016), Sheedy (2018) and McCaughey (2018) provide implicit discussion of the concept. The latter includes the point that Charles Trevelyan, a key figure in his role as Assistant Secretary to the Treasury during the Famine, considered the Famine to be God’s judgement (McCaughey, 2018: 321).

McCaughey (2018: 317) rightly explains continued food exports during the Famine through their placement within laissez-faire economics, and also provides a definition of the term (2018: 306, 316). More broadly, the belief that food exports from Ireland outweighed imports has been a feature of (popular) Famine history ever since Mitchel (1854: 12, 16) included it in his argument that starvation was part of a wilful policy to remove the Irish from Ireland (McGovern, 2009: 36). This, in turn, has fed into the thesis that the Famine was a ‘calculated genocide’, to which scholarship has provided a corrective (Nally, 2008: 733). McCaughey (2018) and Sheedy (2018) include the genocide debate. During 1846 and 1847, at the height of the Famine, grain continued to be exported. While exporting food from a starving country is in itself a morally questionable act, it is the case that during the Famine these exports were significantly reduced compared to previous years, and imports actually exceeded exports after 1846. Furthermore, the grain exported during 1846 and 1847 would not have counterbalanced the amount of potatoes destroyed by the blight. As Ó Gráda (1999: 124) notes, the exported grain would only have compensated for ‘about one-seventh’ of the total amount of potatoes lost.

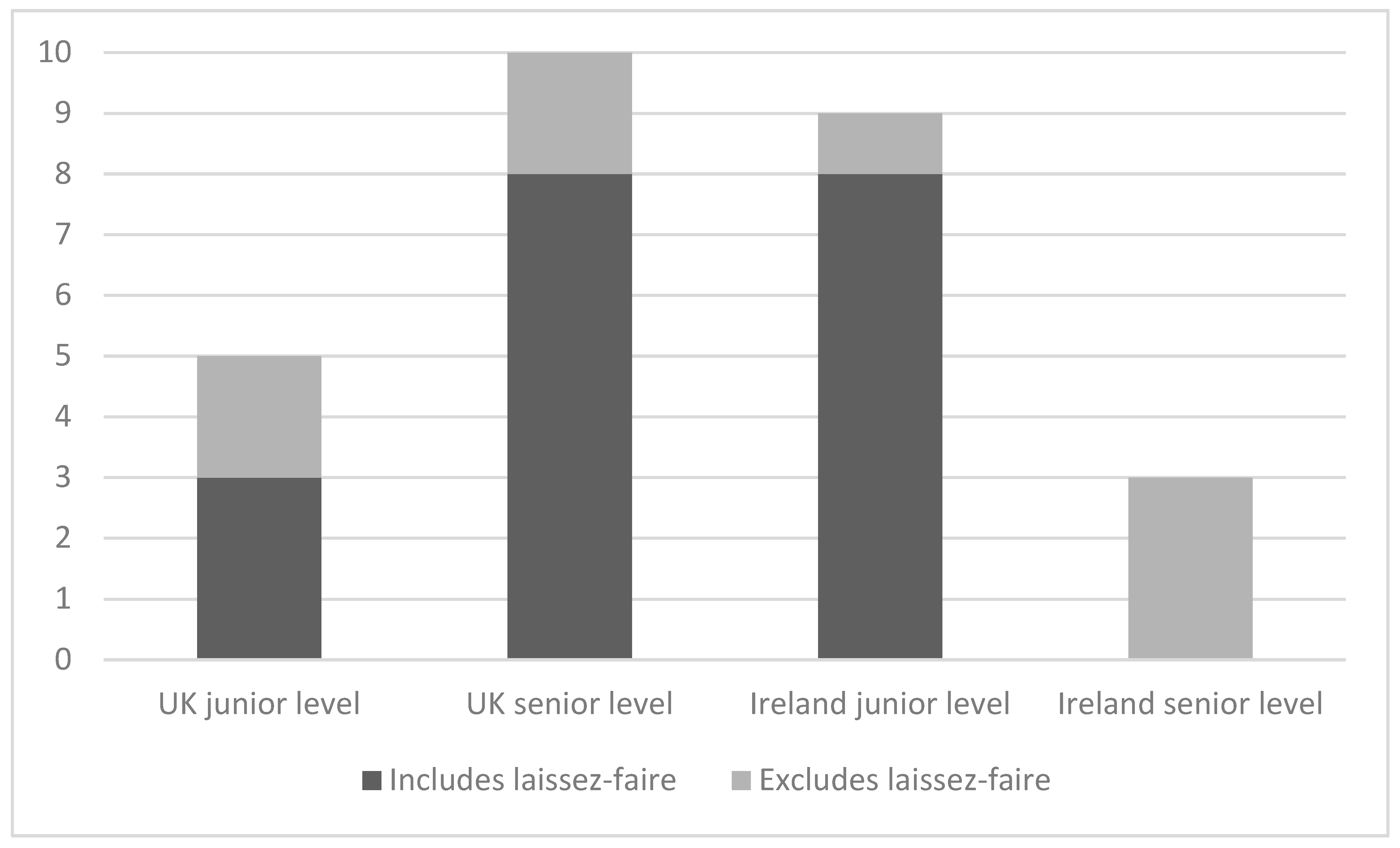

Several textbooks offer nuanced representations of this topic. As Figure 1 shows, 10 out of 27 books include both imports and exports, equally divided between UK senior-level books and Irish junior-level books. Lucey (2018: 193) allows the possibility of engaging with the complexities of the subject by including a table of wheat imports/exports for the years 1844–8, in which imports outweigh exports for the years 1847 and 1848. While reflecting in text on the indignation and violence sparked by continued food exports, McCaughey (2018: 317) similarly includes a table of imports and exports.

Incomplete renderings of the food imports and exports are also found. De Buitléir et al. (2014) mention imports and exports, but on different pages, without any figures and without establishing a relation. Todd and Bottaro (2015: 209) include both imports and exports, but offer a relatively vague rendering: ‘To make things worse, the winter of 1846–7 was very harsh. Although some grain was held back from export, and some was imported, the amount exported was still large.’ Conversely, Adelman and Byrne (2016: 70) acknowledge that ‘grain flooded into the country and offset the food exports that had continued since the early days of the famine’, but that the poor were not able to ‘afford the rocketing prices of the imported wheat and flour’. While this is certainly a valid interpretation, it leaves out the crucial fact that exports did not counterbalance the potatoes lost.

Five (two UK, three Irish) books do not discuss food imports or exports at all, and three (two UK, one Irish) books only discuss exports. Sheedy (2018: 85), for example, only includes that ‘In 1845, Ireland exported 485,000 tons of grain to England, while many people in Ireland starved to death.’ Whether or not textbooks include exports does not align with geographic orientation. By contrast, nine books only discuss imports, and the UK sample tends more often to include only imports (six textbooks, versus three Irish textbooks). This implies a stronger emphasis on British government relief than in the Irish sample.

While some UK textbooks could be more exhaustive, five Irish textbooks do reflect corrective scholarship by providing a balanced account of imports and exports. This suggests that any unbalanced treatment of the topic of imports and exports cannot be considered a remnant of traditional Irish nationalist rhetoric in educational sources. Textbooks that only offer a partial discussion concerning the topic of imports and exports simplify this aspect of Famine history, and do not sufficiently contextualise imports and exports in relation to contemporary tensions between economic ideology and humanitarian aid. Therefore, they run the risk of extending long-standing misinterpretations. It would be worthwhile to explore the complexities of the import/export issue in full detail, especially in textbooks which also ask learners to consider government culpability.

Over two-thirds of the corpus (19 textbooks) engage with laissez-faire, although not all authors use the term, and Fortune (2016), Clare et al. (2015), Wells and Dicken (2015) and Byrne and Shepley (2015) do not explicitly apply the concept to the Famine. The two-thirds consists of both Irish and UK textbooks; as Figure 2 shows, laissez-faire tends to be included more often on the junior level in Ireland, and on the senior level in the UK.

Several books give clear definitions of the concept. Adelman and Byrne (2016: 70; emphasis in original) write:

A greater impediment to vigorous action by the British government was its increasing commitment to the economic principle of laissez-faire . This idea argued that governments must not interfere with market forces and the price mechanism . It stood at the heart of Peel’s policy to reduce taxes on imports and exports, which he followed from 1842 and was then accepted by subsequent governments. Thus, in order not to undermine the interests of traders and retailers, food must not be provided freely or below market prices.

By using the plural ‘governments’, starting from the general principle, rather than from the individual (Prime Minister Robert Peel) or the individual government, and by explicating the connected interests of economic subgroups, this explanation takes into account the broader societal dimension of the term. O’Neill and Jenkinson (2018: 220, emphasis in original) equally include a useful and straightforward definition to explain insufficient governmental aid to the stricken: ‘Help for those affected by the Famine was slow to arrive. The British government took a laissez-faire (“let it be”) attitude to events, believing that a government should not interfere in the economy as it would correct itself eventually.’

In its assignments, this book then offers the potential to work on historical empathy through perspective taking. First, students are prompted to explain laissez-faire, and to consider its relation to government policy; then, they are asked to collaborate and imagine being a politician during the Famine and ‘write down … how you would have helped people. Debate the different ideas with your group’ (O’Neill and Jenkinson, 2018: 221). As a final assignment, the book stimulates students to consider culpability: ‘Do you agree or disagree with the belief at the time that the British government was to blame for the Great Famine?’ (O’Neill and Jenkinson, 2018: 228). Through this sequence, O’Neill and Jenkinson (2018) ask students first to understand the concept, and then to explore different interpretations through imaginative investment, before providing a judgement.

Crucially, while laissez-faire is a complicated concept, its inclusion in the majority of the textbooks discussed above shows that it can be introduced at secondary, and even at junior, level. As Figure 2 shows, while 8 books are geared to advanced levels, 11 books which include laissez-faire are suitable for junior-level students. These 11 are Irish books, while the advanced books are for a UK audience. This does not suggest an overall higher level for junior-level Irish books as compared to UK books; rather, extent of treatment at an earlier level can be linked to the Famine’s place in the Irish junior curriculum.

Laissez-faire ideology was widely supported. Adelman and Byrne (2016: 70) provide a useful discussion of the broader sociopolitical support for laissez-faire principles; Todd and Bottaro (2015: 209; emphasis in original) write that ‘The Whigs were also strong believers in laissez-faire.’ In some books, this more complex societal dimension is not made sufficiently clear, as laissez-faire ideas are linked to individual historical actors. Delap and McCormack (2018: 59, emphasis in original), for example, do not explicitly include the term ‘laissez-faire’, but related features are mentioned in direct connection to Trevelyan: ‘The British Prime Ministers during the 1840s’ both

left the management of the Irish Crisis to a man called Charles Edward Trevelyan. Trevelyan believed it was up to the Irish people to help themselves. He did not want the British government to intervene or to help those suffering, as he worried this would encourage people to be lazy.’

Of course, it is fully justified to assign these convictions to Trevelyan. There is something to be said for seeing an influential politician as shaping his time, but what is left out is the fact that he was also a product of his socio-political and religious context. By not acknowledging that these beliefs were not idiosyncratic but had a wider ideological basis, some books prohibit achieving in-depth historical contextualisation and perspective taking. Consequently, students run the risk of not fully understanding how historical actors came to their decisions, and, importantly, how the historical period differs from their own lives.

Victims and perpetrators

Simplified victim–perpetrator discourses continue to feature in both Irish and UK textbooks. While very few of the textbooks analysed here can be said to be overtly partisan, if they offer simplified narratives, they typically do not provide sufficient ground for historical perspective taking and contextualisation and, by extension, they run the risk of stimulating partial sentiments in young learners. The latter is undesired, especially from the linked perspectives of historical empathy and present-day intercultural awareness. Research on historical understanding and identification processes shown by adolescents in Northern Ireland reveals that partisan accounts begin to feature among 13- and 14-year-olds (Barton and McCully, 2006). This implies that Key Stage 3 is an important stage for the development of historical understanding in young learners (Terra, 2014).

The textbooks offer varying degrees of diversification regarding the hierarchical nature of Irish rural society during the 1840s. Some only speak of ‘the Irish’ as one group, some distinguish between landlords and tenants, and others also provide a more complex image of Ireland’s highly stratified society (landlords, agents, middlemen, strong farmers, small farmers, cottiers, landless labourers). More complex constellations can be found in, for example, Lucey (2018: 187–9), Henry et al. (2018: 211–12, and its Activity Book) and Rees (2018: 110–14). Explicit variegation between the various subgroups can provide a more exact historical understanding of the complexities in the demographic and societal effects of the Famine.

In the majority of the Irish and UK textbooks analysed here, the Irish are generalised as victims, which aligns with Janmaat’s (2012) findings for earlier Irish textbooks. While I do not want to deny that the Irish poor suffered most during the Famine, generalisation does efface differences in victimhood. Moreover, a more complex narrative would provide room for subjects who cannot easily be subsumed under the categories of victim or culprit. Tenants availing themselves of the opportunity to rent land that others could no longer afford, for example, did not commit illegal acts, but they benefited at the expense of their worse-off peers. In the Activity Book to Henry et al. (2018: 215), a graph showing the decrease of small landholdings and increase of large holdings after the Famine is included. Students are asked to study the graph and to explain the decrease, not the increase. Although reflecting on a key consequence of the Famine, the activity does leave out explicit mention of those who profited from the changes in Ireland’s land system. Adelman and Byrne (2016: 75) include the point that some speculators and surviving landlords profited from the crisis through the Encumbered Estates Act, which was established in 1849 to facilitate the sale of estates from insolvent landowners. Functioning as implicated subjects (Rothberg, 2019), these varied historical actors contributed to maintaining a corrupt and highly unequal land system.

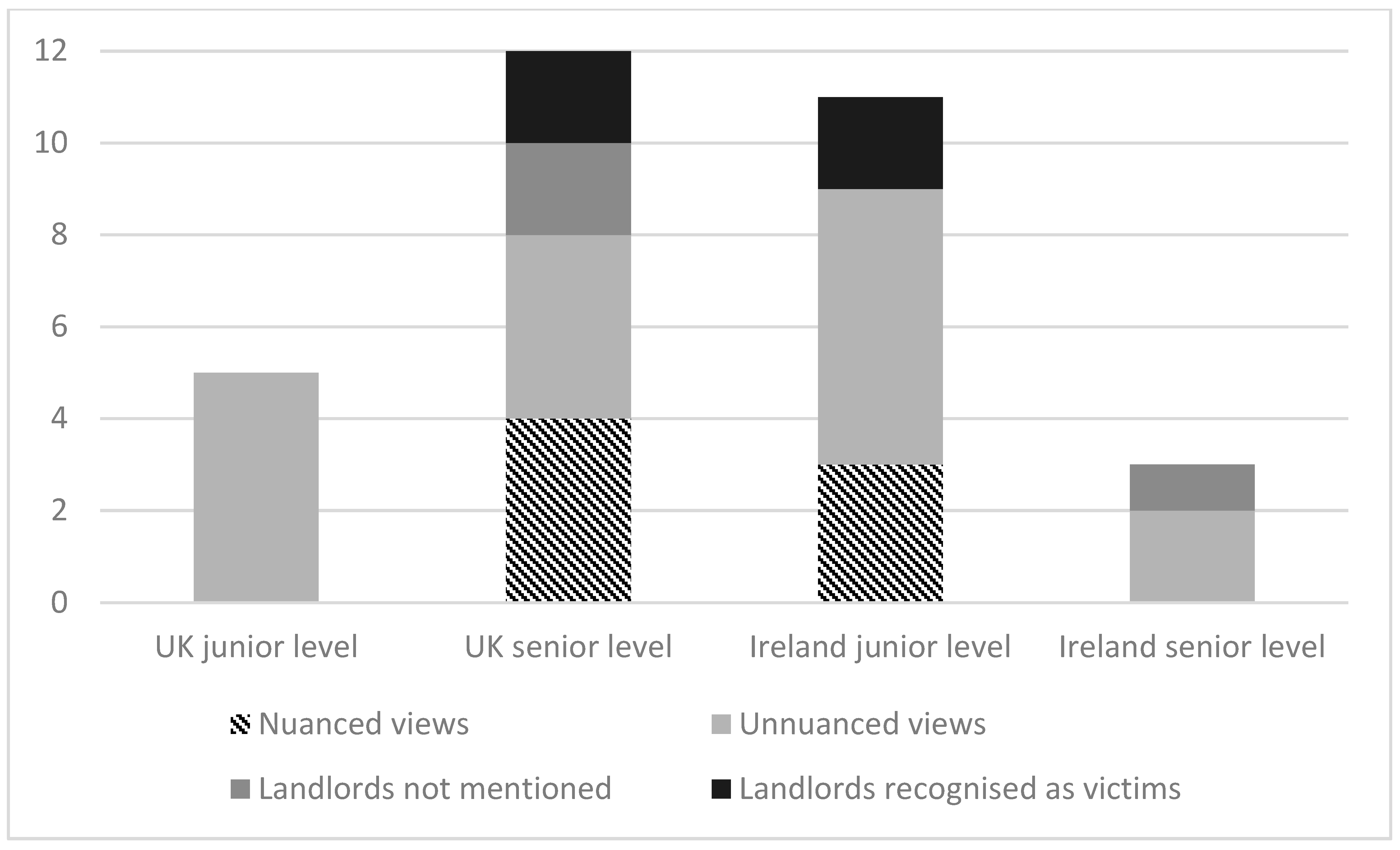

Figure 3 provides insight into how landlords are represented in the textbook corpus. While four advanced-level UK books and three junior-level Irish books provide a relatively nuanced view of landlords and their motives, also, for example, acknowledging their effort to help their tenantry, 17 offer more stark and typically negative depictions (and 3 books do not mention landlords). The majority of the corpus (23 books) do not discuss the landowning classes as victims. Hughes et al. (2018: 8–9) cast landlords as perpetrators, keen to make a profit or acting out of ill intentions. Exclusion of landlords from the category of victim is sometimes done explicitly, but also sometimes implicitly. Stout and Lucey (2018: 112–13), for example, ask students to draw their conclusions about primary quotations from the Famine era, but by only providing sources which focus on poor victims, and which negatively portray bailiffs and landlords, the book is suggestive in the exercise.

Not all landlords were out to clear the Irish poor off their lands, and some landlords were destitute or sought to save rather than to expel their tenants when offering assisted emigration, or were at least motivated by a combination of conflicting reasons (McGowan, 2017: 93–4). Of course, this comment should not be understood as a disclaimer for the evils of British imperial rule, the corrupt land system in Ireland, or the misdeeds of landlords; rather, it is meant to again stress the complexity of human roles. In line with this, O’Neill and Jenkinson (2018: 219) and McCaughey (2018: 314) acknowledge that some landlords also reduced rents; the latter also includes that some landlords offered assisted emigration as a form of aid. Kidson (2016: 120, 126) acknowledges misdeeds committed by landlords, but equally provides a nuanced understanding of their situation and motivations. Adelman and Byrne (2016: 72–6) provide a distinction in how the various (sub)classes were impacted by the Famine, explaining that while the lowest classes were hit hardest, landlords were also impacted, while better-off farmers weathered the crisis relatively well. McCaughey (2018: 323), moreover, intriguingly challenges Irish students to imagine that they are the historical other. The book asks students to write on three possible topics, including the ‘Life of a landlord during the Famine’. This assignment has the potential to make students aware of the effects of the Famine beyond its Irish victims, and helps to acknowledge the complexity of the catastrophe and concomitant responses. The examples in this paragraph are from both UK and Irish sources, demonstrating that such multifaceted interpretations feature across the textbook corpus.

Moreover, the examples suggest that introducing the concept of ‘implicated subject’ in textbook discussions of the Famine would be conducive to a better understanding of Ireland’s land system, its interpersonal relations, and the prolongation of existing historical inequalities. In this context, it is vital to acknowledge that there are different types of suffering, and that it would be inappropriate to gloss over these differences. Crucially, for present-day learners, a narrow view of victimhood prevents full historical contextualisation and perspective taking. A simplified understanding of how the Famine hit the poor but not the rich fails to demonstrate the actual pervasiveness of the catastrophe. By extension, understanding that the effects of the Famine were not limited to one group – whether that group is distinguished on the basis of class, religion or nationality – can also help young learners understand that for other demographic catastrophes, consequences are often not clear cut, and do not neatly follow class or group lines.

Conclusion

More extensive discussions of the key contested topics part of the historical narrative repertoire of the Great Irish Famine tend to be included in UK advanced-level textbooks, while they are already included at junior level in Irish textbooks. This should be tied to the Famine’s placement in the respective national curricula, rather than to the overall level of difficulty of Irish versus UK history textbooks. When exploring the causes and historical development of the Famine, UK and Irish history textbooks only rarely include providentialism. Both UK and Irish textbooks frequently include laissez-faire and the linked concepts of imports/exports; UK textbooks tend to include only imports more often than do their Irish counterparts. Finally, most simplification takes place in relation to human subject positions, as Irish victims are often homogenised into one group, victim–perpetrator discourses, remain contrastive, and landlords are typically cast in stark terms, with concomitant omission of their potential victimhood. Apart from the amount of space dedicated to the Famine, which can be linked to placement within national curricula, the analysis shows that these differences feature across the corpus, and therefore cannot convincingly be linked to geographic or political orientations.

While several of the history textbooks discussed in this article provide nuanced representations of the Famine, through simplification others give insufficient opportunity for learners to develop a well-rounded knowledge of the historical context of the Famine. Such knowledge is needed for understanding the historical period and actors, and how the latter are shaped by their own specific set of ideological convictions. In the past, unqualified interpretations of the Famine have served partisan – both unionist and nationalist – discourses. More specifically, the complexities of victim–perpetrator discourses, while acknowledged in Irish studies (Ó Gráda, 2015), and in memory studies scholarship (Rothberg, 2019) more broadly, are not sufficiently showcased in the majority of the history textbooks analysed here. It is advisable to provide space for more complex positions of implication in textbook discussions of the Famine. For Irish students, for example, not including the landlord as a potential victim can impede perspective taking for this historical other.

Sympathy for the historical counterpart of one’s own cultural group then remains possible, but empathy for the historical other becomes much harder to achieve. Many scholars and teachers of social studies education see history as a subject suitable for the stimulation of historical, and, by extension, present empathy and ‘prosocial democratic behavior’ (Endacott and Brooks, 2018: 208). As such, if a textbook does not provide sufficient support for historical perspective taking, contextualisation and empathy formation regarding a contested issue such as the Famine, an opportunity is missed to address long-standing contradictions which sustain the controversial nature of this issue in the present.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Ingrid de Zwarte, Marguérite Corporaal, Anne van Mourik and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments on an earlier version of this article.

Declarations and conflicts of interest

Research ethics statement

Not applicable to this article.

Consent for publication statement

Not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of interest statement

The author declares no conflict of interest with this work. All efforts to sufficiently anonymise the author during peer review of this article have been made. The author declares no further conflicts with this article.

References

Adelman, P; Byrne, M. (2016). Access to History: Great Britain and the Irish question 1774–1923. London: Hodder Education.

Armstrong, B. (2020). Access to History: Britain 1783–1885. London: Hodder Education.

Assmann, A; Detmers, I. (2016). ‘Introduction’. Empathy and its Limits. Assmann, A, Detmers, I I (eds.), Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 1–17.

Bartelds, H; Savenije, G.M; Van Boxtel, C. (2020). ‘Students’ and teachers’ beliefs about historical empathy in secondary history education’. Theory & Research in Social Education 48 (4) : 529–51, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2020.1808131

Barton, K.C; Levstik, L.S. (2004). Teaching History for the Common Good. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Barton, K.C; McCully, A.W. (2006). ‘History, identity, and the school curriculum in Northern Ireland: An empirical study of secondary students’ ideas and perspectives’. Journal of Curriculum Studies 37 (1) : 85–116, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0022027032000266070

Boylan, C. (2017). ‘The Great Famine in Irish history textbooks, 1900–1971’. Children’s Literature Collections: Approaches to research. O’Sullivan, K, Whyte, P P (eds.), New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 53–69.

Brockie, G; Walsh, R. (2016). Modern Ireland. 3rd ed. Dublin: Gill Education.

Brockie, G; Walsh, R. (2020). Modern Ireland. 4th ed. Dublin: Gill Education.

Bruce, L; Cloake, J.A; Newman, K; Wilkes, A. (2016). Thematic Studies c790–Present Day. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Byrne, M; Shepley, N. (2015). AQA A-level History: Britain 1851–1964: Challenge and transformation. London: Hodder.

CCEA (Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment). (2017). GCSE Specification in History. Belfast: CCEA.

CCEA (Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment). (2019). GCE Specification in History. Belfast: CCEA.

Chapman, A. (2021). ‘Introduction: Historical knowing and the “knowledge turn”’. Powerful Knowledge and the Powers of Knowledge. Chapman, A (ed.), London: UCL Press, pp. 1–31.

Clare, J.D; Bates, N; Fisher, A; Kennett, R. (2015). Making Sense of History, 1845–1901. London: Hodder Education.

Coogan, T.P. (2012). The Famine Plot: England’s role in Ireland’s greatest tragedy. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

De Buitléir, M; Henry, G; Nyhan, T; Tonge, S. (2014). Timeline: A complete history text for Junior Certificate History. Dublin: Edco.

Delap, S; McCormack, P. (2011). Uncovering History. Dublin: Folens.

Delap, S; McCormack, P. (2018). Time Bound. Dublin: Folens.

DfE (Department for Education). (2014a). History GCSE Subject Content. London: Department for Education.

DfE (Department for Education). (2014b). The National Curriculum in England: Key Stages 3 and 4 framework document. London: Department for Education.

Doyle, A. (2002). ‘Ethnocentrism in history textbooks: Representation of the Irish Famine 1845–49 in history textbooks in English schools’. Intercultural Education 13 (3) : 315–30, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14675980213710

Endacott, J.L. (2014). ‘Negotiating the process of historical empathy’. Theory & Research in Social Education 42 (1) : 4–34, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2013.826158

Endacott, J.L; Brooks, S. (2018). ‘Historical empathy: Perspectives and responding to the past’. The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. Metzger, S.A, McArthur Harris, L L (eds.), Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 203–25.

Fortune, A. (2016). Oxford AQA History: Challenge and transformation: Britain c1851–1964. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frawley, O. (2014). ‘Introduction: Cruxes in Irish cultural memory: The Famine and the Troubles’. Memory Ireland, Volume 3: The Famine and the Troubles. Frawley, O (ed.), Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press, pp. 1–14.

Fuchs, E; Otto, M. (2013). ‘Introduction: Educational media, textbooks, and postcolonial relations of memory politics in Europe’. Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society 5 (1) : 1–13, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2013.050101

Goldberg, T; Savenije, G.M. (2018). ‘Teaching controversial historical issues’. The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. Metzger, S.A, McArthur Harris, L L (eds.), Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 503–26.

Government of Ireland, NCCA (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment) and the Department of Education and Skills. (2017). Junior Cycle History Specification,

Gray, P. (1995). ‘The triumph of dogma: Ideology and famine relief’. History Ireland 3 (2) : 26–34. https://www.historyireland.com/the-triumph-of-dogma-ideology-and-famine-relief/ . Accessed 22 February 2023

Gray, P. (2013). ‘Famine and land, 1845–80’. The Oxford Handbook of Modern Irish History. Jackson, A (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 544–61.

Henry, G; Kennedy, B; Nyhan, T; Tonge, S. (2018). History Alive. Dublin: Edco.

Hughes, M; Hume, C; Robertson, H. (2018). National 4 & 5 History Course Notes. Glasgow: Leckie/Collins.

Janmaat, J.G. (2012). ‘History and national identity construction: The Great Famine in Irish and Ukrainian history textbooks’. Holodomor and Gorta Mór: Histories, memories and representations of famine in Ukraine and Ireland. Noack, C, Janssen, L; L and Comerford, V V (eds.), London: Anthem Press, pp. 77–102.

Janssen, L. (2018). ‘Diasporic identifications: Exile, nostalgia and the Famine past in Irish and Irish North-American popular fiction, 1871–1891’. Irish Studies Review 26 : 199–216, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09670882.2018.1446401

Kenny, K. (2000). The American Irish: A history. New York: Longman.

Kidson, A. (2016). Edexcel A Level History. Paper 3: Ireland and the Union, c1774–1923. Harlow: Pearson.

Klerides, E. (2010). ‘Imagining the textbook: Textbooks as discourse and genre’. Journal of Educational Media, Memory, and Society 2 (1) : 31–54, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2010.020103

Korostelina, K.V. (2013). History Education in the Formation of Social Identity: Toward a culture of peace. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Krippendorf, K. (2004). Content Analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Lloyd, D. (2000). ‘Colonial trauma/postcolonial recovery?’. Interventions 2 (2) : 212–28, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/136980100427324

Lucey, D. (2018). Making History: Complete Junior Cycle history. Dublin: Gill Education.

Mac Gearailt, C. (2018). ‘Writing the Irish past: An investigation into postprimary Irish history textbook emphases and historiography, 1921–69’. History Education Research Journal 15 (2) : 233–47, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18546/HERJ.15.2.06

Mac Suibhne, B. (2013). ‘A jig in the poorhouse’. Dublin Review of Books, April 2013 https://drb.ie/articles/a-jig-in-the-poorhouse/ . Accessed 23 October 2021

McCarthy, P. (2010). Junior Certificate History: Footsteps in time 1. Dublin: CJ Fallon.

McCaughey, P. (2018). Discovering History: New Junior Cycle history. Dublin: Mentor Books.

McGovern, B.P. (2009). John Mitchel: Irish nationalist, Southern secessionist. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press.

McGowan, M. (2017). ‘The Famine Plot revisited: A reassessment of the Great Irish Famine as genocide’. Genocide Studies International 11 (11) : 87–104, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/gsi.11.1.04

Mitchel, J. (1854). Jail Journal; Or, five years in British prisons. New York: Office of The Citizen.

Mitchel, J. (1871). Ireland Since ’98. Daniel O’Connell; The Repeal agitation; The miseries of the Famine; The Young Ireland Party, etc. Glasgow: Cameron and Ferguson.

Morash, C. (1995). Writing the Irish Famine. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Nally, D. (2008). ‘“That coming storm”: The Irish Poor Law, colonial biopolitics, and the Great Famine’. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 98 (3) : 714–41, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00045600802118426

NCCA (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment). (). n.d.. ‘Junior Cycle’. www.curriculumonline.ie/Junior-cycle/ . Accessed 31 May 2022

Ó Gráda, C. (1999). Black ’47 and Beyond: The Great Irish Famine in history, economy, and memory. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ó Gráda, C. (2001). ‘Famine, trauma and memory’. Béaloideas 69 : 121–43, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/20520760

Ó Gráda, C. (2015). Eating People Is Wrong, and Other Essays on Famine, Its Past, and Its Future. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

O’Neill, G; Jenkinson, E. (2018). Artefact. Castleisland: Educate.ie.

Peal, R. (2017). Knowing History: KS3 History Modern Britain 1760–1900. London: Harper Collins.

Rees, R. (2018). Ireland Under the Union 1800–1900. Newtownards: Colourprint Educational.

Repoussi, M; Tutiaux-Guillon, N. (2010). ‘New trends in history textbook research: Issues and methodologies toward a school historiography’. Journal of Educational Media, Memory & Society 2 (1) : 154–70, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2010.020109

Rothberg, M. (2019). The Implicated Subject: Beyond victims and perpetrators. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Sheedy, D. (2018). History in Focus 1: A history of Ireland for the Junior Cycle. Dublin: CJ Fallon.

SQA (Scottish Qualifications Authority). (2019). Higher Course Specification. Glasgow: SQA.

SQA (Scottish Qualifications Authority). (2021). National 5 Course Specification. Glasgow: SQA.

Stout, S; Lucey, D. (2018). Making History: Skills book: Complete Junior Cycle history. Dublin: Gill Education.

Terra, L. (2014). ‘New histories for a new state: A study of history textbook content in Northern Ireland’. Journal of Curriculum Studies 46 (2) : 225–48, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2013.797503

Todd, A; Bottaro, J. (2015). History for the IB Diploma Paper 2: Independence movements (1800–2000). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tóibín, C. (2004). ‘The Irish Famine’. The Irish Famine. Tóibín, C, Ferriter, D D (eds.), London: Profile Books.

Twomey, P. (2016). The Making of Ireland. Castleisland: Educate.ie.

Van Berkel, M. (2017). ‘Plotlines of Victimhood: The Holocaust in German and Dutch history textbooks’. PhD thesis. Erasmus University.

Wells, M; Dicken, M. (2015). OCR A Level History: Britain 1846–1951. London: Hodder.

Wertsch, J.V. (2002). Voices of Collecting Remembering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wilkes, A. (2014). KS3 History – Industry, Invention and Empire: Britain 1745–1901. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilkes, A. (2020). KS3 History – Revolution, Industry and Empire: Britain 1558–1901. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

WJEC (Welsh Joint Education Committee). (2016). WJEC GCSE in History. Cardiff: WJEC.

Wood, S; Wood, C. (2018). National 4 & 5 History: Migration and Empire 1830–1939. 2nd ed. Paisley: Hodder Gibson.