Introduction

Even in the digital age, the position of the textbook is dominant within school history teaching. It has a significant effect on what is taught, and it is often seen as so authoritative by teachers and students alike that it is regarded as distilled truth (Edwards, 2008; Johanson, 2015; Nichol and Dean, 2003; Paxton, 1999). On a larger scale, the syllabus acts as an instrument of selection, with teachers orienting their practice to it even when they are sceptical of incoming changes (Harris and Graham, 2019). What, then, happens in the absence of both textbook and syllabus? Is it possible to learn history informally, before being able to read, and perhaps even before understanding the difference between the past, the present and the future? If we are to believe a Norwegian research field on history in the kindergarten, it may be done in spite of those hindrances.

Norwegian kindergartens are day-care centres for children up to six years of age. Originally established in the 1970s to enable the mothers of preschool children to enter the labour market, their responsibilities have since snowballed. Their importance has grown, commensurate with the number of children attending. In 2019, the proportion of all one-to-five-year-olds enrolled in kindergartens reached 92.1 per cent, having risen from 62 per cent in 2000 (Statistisk Sentralbyrå, 2021: 4). Now tasked with helping to reduce the inequalities which are manifest even in the early years, they have always had a role in promoting health. The exact parameters within which the institution of the kindergarten should exist have become a cause of contention. Should it, in fact, provide an education? In 2006, responsibility for kindergartens was transferred from the Department of Children and Families to the Department of Education. This was seen as symbolic by proponents of learning in the kindergarten. Such views, however, have their detractors. Traditionalists are sceptical about too many ‘scholastic’ activities being imposed upon young children, and they are able to back up their arguments with international research (Gray, 2011; Sommer, 2015; Sundsdal and Øksnes, 2015).

The official documents reflect a compromise between these two views. The most recent Kindergarten Act of 2005 mentions both the child’s ‘need for care and play’ and the promotion of ‘learning and socialisation as a basis for personal development’ (Kunnskapsdepartementet, 2018: 7). Because enrolment is voluntary, kindergarten is not regarded as a rung on the educational ladder, but nor is it a mere playgroup. Even the first Kindergarten Act of 1975 declared the institution to be an ‘approved pedagogically designed service’ (Korsvold, 2016: 161). Each kindergarten was to employ personnel with teaching qualifications. Since 1996, there has also been a national curriculum for kindergartens. Because it primarily concerns the broad principles which govern activities, it is known as the Framework Plan. The current version, from 2017, has nine chapters, the last of which gives details of seven ‘subject areas’ which help organise content. Within one of these, called ‘The Local Environment and Community’, there are two bullet points (out of 13) which pertain to historical studies. The first is that children are to become familiar with local history and local traditions. The second is that they should be told that they are part of a society undergoing change, with a past, present and future.

This article aims to discover whether this informal approach, with no set syllabus or classes, nevertheless succeeds in introducing history. All history teaching in schools or kindergartens in Norway today is informed by the precepts of history didactics (similar to public history in English-speaking countries). It matches the emphasis in other countries that historical thinking is more important than historical facts (Mathis and Parkes, 2020; Nitsche et al., 2022). One of the axioms is that history is everywhere. Individuals learn it by social osmosis through, among other things, the media, conversations, illustrations, travel, statues and monuments (Jensen, 1994; Jordanova, 2019; Pinto and Ibanez-Etxeberria, 2018). Such an approach can meaningfully be applied to kindergartens. The children who attend do not yet have access to all the quotidian sources of information, but their natural curiosity ensures that they are learning all the time.

Through a wide definition of history, along these lines, the intention is to reach a conclusion about how much, how and where history appears in Norwegian kindergartens. As the national curriculum allows the kindergartens considerable autonomy in what they emphasise, it is proposed to interrogate these questions by means of a local study. The method requires close reading of the individual documents associated with different kindergartens, supplemented by interviews to gauge how accurate these are. Earlier attempts to reach a greater number of kindergartens directly by means of a questionnaire were not successful. History is often a marginal topic in kindergartens, and while most wish to apply the national curriculum, it is not a subject which is prioritised greatly, even in schools. There has not been a subject called ‘history’ since 1969 in compulsory education (see Raugland, 1996). History was a component of ‘social studies’ with its own syllabus until 2020, when boundaries between it and the two other components, geography and civics, were dissolved (see Saabye, n.d.).

History in the kindergarten

This relative neglect of history stands in contrast to how the subject fares in other educational systems. Hilary Cooper (2013) claims the following for British five-year-olds: that they can speak about themselves in the past, understand differing cultures, react to narratives and obtain information through asking questions and manipulating objects. Norwegian history education research is often sceptical about how much young children are able to comprehend. Thus, the most recent addition to the literature sees Cooper as somewhat ‘optimistic’ about what may be attained by the age group (Moen et al., 2021: 82). This had also been the international view until the 1980s (Arias-Ferrer et al., 2019). More recently, an American investigation found that primary school pupils, and some still in kindergarten, were able to distinguish between photographs from the past which were ‘older’ and ‘newer’ (Barton and Levstik, 2008). It is usual for five- and six-year-olds to regard themselves as existing continuously between the past and future, with many able to give detailed accounts of events in the past (Jalongo, 2019). The same age group primarily divides the past between ‘long ago’ and ‘close to now’ (De Groot-Reuvekamp et al., 2017).

The Norwegian literature nevertheless sees multiple benefits from learning history in early childhood. History helps with identity formation and immersion in society and its culture (Skjæveland et al., 2013). It stimulates all-round development, and it is easy to combine with other subjects (Skjæveland, 2017). Learning about the past increases children’s vocabulary (Nordstrand and Karsrud, 2014). This is because outdated concepts remain within the language. For example, a book about knights in use in Norwegian kindergartens included words new to children, such as ‘esquire’, ‘chain mail’ and ‘crusade’ (Askeland and Maagerø, 2011: 124). Parents report that their children utilise such words in new contexts, proving mastery of their core meaning. History as a subject increases one’s knowledge, provides new settings to be explored in play, and may bring new projects in its wake (Fønnebø and Jernberg, 2018). In this context, I contend that local history can easily become more general. This local study is set in Kristiansand, the largest city in southern Norway. As a port, it was known for its many sailing ships in the nineteenth century. On a kindergarten level, knowledge about these may become a project about historical means of transport. Children love stories, and if they are from real life, they learn something about the world which they inhabit (Bøe, 1999). History may be visualised and experienced locally. Many areas contain remnants of important historical topics such as the Middle Ages and industrialisation (Kjeldstadli, 2013). An unknown item from the past may immediately stimulate wonder and engagement (Lund, 2020). Concepts of time are undoubtedly important in history education, but they also matter in being able to structure other narratives correctly (Gjems, 2007).

While a local study on its own is not enough to make judgements regarding the entire country, the results obtained here should be taken in conjunction with what others have discovered. The present research links most closely to an investigation conducted by Kari Hoås Moen and Ellen Holt Buaas (2012) in the city of Trondheim and its surroundings. They set out to discover the extent to which history had a presence in the kindergartens accepting their students on work placements. As they had prior connections with the teachers, they were able to obtain as many as 142 responses to their questionnaire examining how and where history appeared (Moen and Buaas, 2012). The respondents saw history as having ‘some’ presence in their institutions. It emerged primarily in storybooks and, to a lesser degree, in songs and traditional games. They believed history to be most prevalent in another subject area, ‘Communication, Language and Text’, rather than in ‘The Local Environment and Community’. This is an interesting finding, as it suggests that the teachers saw history more as a literary endeavour than as a social science amenable to being ‘constructed’ locally. The previous national curriculum from 2006, valid at the time, stated that ‘social studies’ should also be learned from books. In any case, history began as literary chronicles of events, and it was only after Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886) pioneered the use of primary sources that it started taking on some of the characteristics of a social science (Boldt, 2014). Few of the teachers reported specialised knowledge of the subject, and it seems more intuitive, at least at this level, to regard it as literature.

The local, as opposed to the national, was upgraded in the national curriculum of 2017. But even the previous version laid considerable emphasis upon what takes place locally. This is partly a consequence of the position that Reggia Emilia pedagogy holds in Norwegian kindergartens (Hammer, 2017; Moen et al., 2021), which seeks to integrate the child into the natural and local environment. In this constructivist approach, the young learner is encouraged to make his or her own personal discoveries. According to the curriculum, history is supposed to be ‘constructed’ in the local environment through excursions to notable places and interaction with their inhabitants, especially those who have roots in the area. Since the children are not expected to be able to read, social constructivism is inevitably used.

The best developed scheme of which I am aware, encompassing, but not limited to, the history of the industrial conglomerate Hydro, began with simple enquiries by a kindergarten in Notodden, a UNESCO world heritage site, about the church, shop, plots of land and notable farms in its vicinity. As an illustration of the interest generated, a five-year-old boy equipped himself with a hat, a wheelbarrow and a spade, which caused a girl of the same age to interject, ‘Oh no, here comes a day labourer’ (Nordstrand and Karsrud, 2014: 62–3). Even a much less time-consuming teaching method, the use of a picture book including Kristiansand landmarks, made a three-year-old girl exclaim when on an outing, ‘There is the cathedral, for real, and there he is!’, pointing to the statue of local poet and historian Henrik Wergeland (Horrigmo, 2014: 159).

The local area is regarded as a starting point for immersion into wider society (Horrigmo, 2014; and see Cooper, 1994). As the curriculum includes a bullet point about instilling consciousness of how societies change over time, this may be exemplified by the local. Through their own knowledge of the local community, children may gain an appreciation that shops come and go, playgrounds are relocated, and newcomers move into the area, while some old-timers depart (Harnett, 2007) The resulting understanding may gradually be expanded to include the point that such processes have not ended, and hence there will be further changes in the future.

Another gateway to the past in the curriculum is provided by the culture and history of the Sami people. They are the Indigenous people of Norway, having settled in most of the land before records began. Despite being as diverse and modern as any other Norwegians, their traditional lifestyle contains many remnants of the past, especially related to nomadism and closeness to nature. Examples include the lavvu (tent), a temporary dwelling similar to the North American tipi, and belief that natural phenomena have souls. In their core areas, where Sami languages have equal status to Norwegian, the national curriculum orders kindergartens to concentrate on Sami culture. In other kindergartens, the mandatory inclusion of Sami elements provides an enrichment of their pedagogy. There are many opportunities to learn about history in dealing with an old culture. It need not be tethered exclusively to Sami life, and it may provide inspiration for deeper learning. Sami traditional handicrafts, called duodji, match Viking-era practice of making everyday objects artistic. Sami child rearing, with its focus on learning through practical tasks under the guidance of the parents, was common among other Norwegians too in previous centuries. Since they were accorded Indigenous status in 1990, there has been a revitalisation of the Sami identity across Norway (Evjen, 2009; Pedersen and Høgmo, 2012). In kindergartens, history is a local endeavour, but through focusing on the Sami as a people, a nationwide history may emerge. This is a paradox, as provision is not made for a national Norwegian history (although nothing in the curriculum actively discourages it either).

Method

As mentioned, this study focuses upon the Kristiansand local authority. Principally a city, its surroundings also include some semi-rural areas which were incorporated into it in 2020. In 2021, Kristiansand had 112,588 inhabitants. It contained 104 kindergartens in total, of which 36 were run by the local authority, 50 were private and 18 were managed by families (thus private, but not subject to the same regulations as the larger institutions). To gauge to what extent history was present in these kindergartens, I studied the yearly plans of all the kindergartens which had published them online. Such a procedure does not catch tacit knowledge, that is, what happens automatically in the kindergartens without much awareness that history is involved, but it does have advantages too. First, the procedure allowed the kindergartens to present what they do of their own accord, without outside pressure, and to decide for themselves what is important enough to merit inclusion in their plan. The procedure still provides a pointer to how much history is contained in their daily work. Second, the procedure was made autocorrecting through being supplemented by interviews. This allowed consideration of how important the yearly plans really were. However, since history only forms a small part of the subject area ‘The Local Environment and Community’, and since there are six other subject areas, finding clear use of history in each individual kindergarten is not straightforward.

A method of extracting historical content had to be devised, based upon topics and areas that were likely to include some historical information, or which accorded with the principles of history didactics, perhaps echoed in the national curriculum. The latter primarily involves activities to make children conscious about the passage of time, such as focus on the life cycle of an individual (mentioned under the subject area ‘Nature, the Environment and Technology’) or historical change (societies having a past, present and future). To start with, anything which might include historical elements was noted down, including culture, traditions, contact with elderly people, and even professional art. The idea was that in order to find historical elements, the net would initially have to be cast widely, but that the data would then be refined until only genuine history education remained. With so little actual national history in the curriculum, ‘history’ had to be defined broadly to include anything from the past and the principle of change over time.

The yearly plans published by individual kindergartens thus constitute the main primary source. Compiling such a plan is a legal requirement under the Kindergarten Act of 2005, but it need not be in the public domain, and there is no template for how to write it. Others have considered that this flexibility makes it a potent document for open-ended research (Likestillingssenteret, 2010). Typically, it provides the main pedagogical principles to which the kindergarten in question adheres, what it emphasises, and general information about the institution. As the yearly plans differ in scope, and as interdisciplinary activities are encouraged, topics which were mentioned regularly, and which could potentially include history, were chosen. There is no actual history syllabus, and previous research has shown that ‘The Local Environment and Community’ subject area is often neglected (Dingstad, 2012; Østrem et al., 2009). One large private chain studied in the present investigation merged it with another subject area, making it almost disappear. To find the presence of history, the following categories were chosen: local history, Sami culture, extended celebrations of Constitution Day with a historical explanation, visits to museums or monuments, concepts of time or the life cycle, traditional games, religion, social interaction with elderly people, fairy tales, and art and culture.

Some of these are more clearly historical than others. Religion concerns life in ancient societies, and it was thus judged to have the potential to convey historical information. Norwegian fairy tales, compiled by Peter Christen Asbjørnsen and Jørgen Moe in the nineteenth century, are folklore and, for this reason, are almost a primary source about life in bygone days (Kaplan, 2003). Because visual arts often depict the past, and culture is something which grows organically over time, these were also included. One of the most promising categories, projects, could not be maintained, as no kindergarten mentioned them in its yearly plan for 2020/1. From reading the yearly plans in previous years, and from knowledge of the research literature, it is certain that such projects do take place, and that they usually encompass history. However, the chosen method did not allow it to be stated positively that there were such projects underway in Kristiansand kindergartens in 2021.

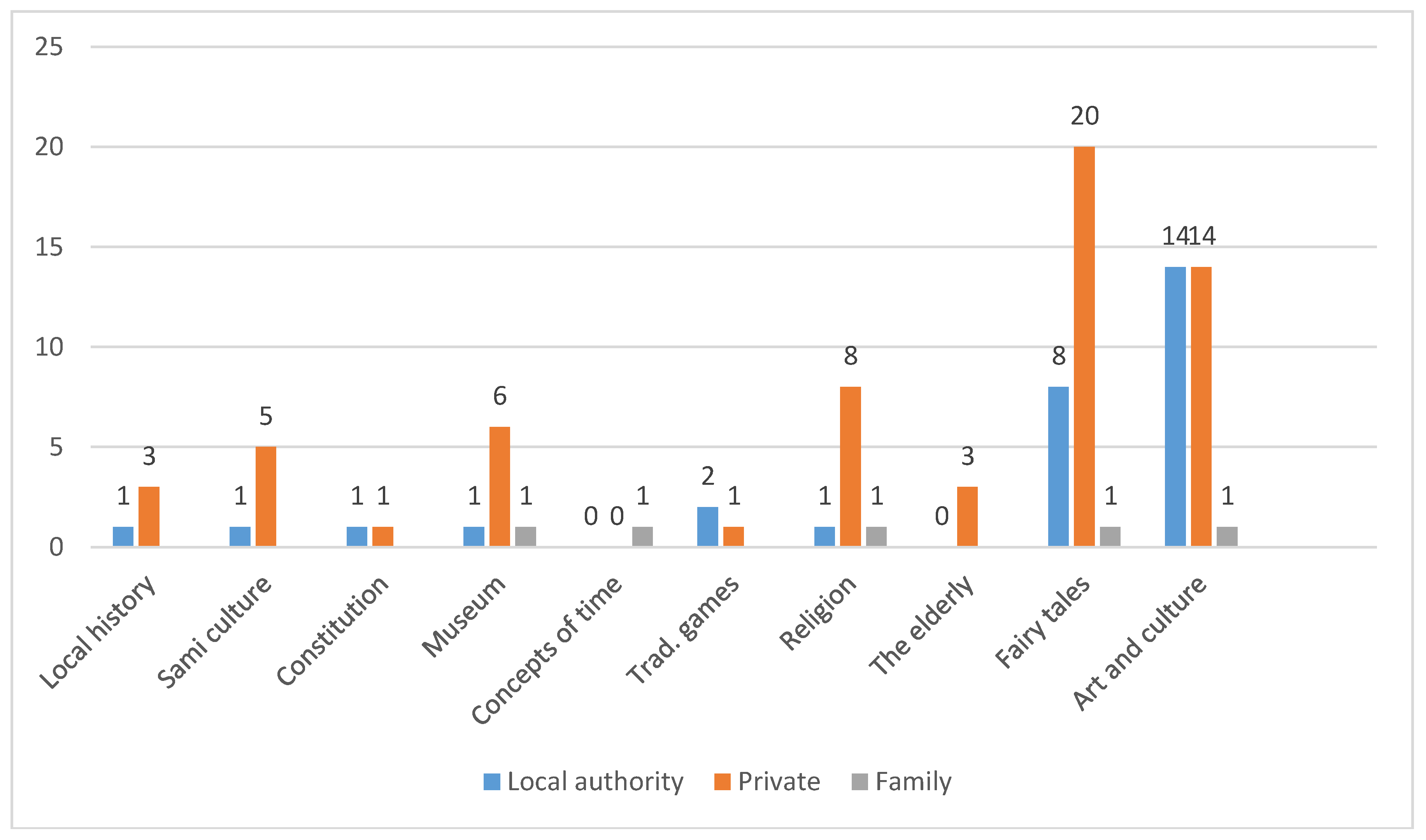

The yearly plans were read systematically between 16 and 18 August 2021. Only the plans for that year or, if necessary, the preceding academic year were considered. Not all the yearly plans were available online; therefore, information was gathered about 25 kindergartens under local authority management, 36 private institutions and 2 family-run institutions. Each of these yearly plans was read, and if it gave a clear indication that a particular category was represented, it was noted on a ready-made form. Two of the categories were almost universal, namely Sami culture and celebration of Constitution Day. For this reason, it was necessary for a kindergarten to describe their activities relating to these in some detail, if they were to be noted down under these headings. This was to ensure that historical elements were likely to be present in these run-of-the-mill activities. For many people, Constitution Day, occurring on 17 May, is simply an excuse for a party, with very limited historical content. Similarly, although Sami culture is clearly respected, it is apt to be portrayed in such basic terms (colouring in the Sami flag, or hearing about reindeer herding) that no real history is involved (Myrstad, 2021). If other topics which potentially contained history were mentioned, these were noted down, and afterwards related to the category which they most closely matched. Excursions to a library were recorded under museums, for instance, since libraries often contain displays and temporary exhibitions. After gathering the information, it was tallied according to the type of kindergarten (local authority, private or family-run), as shown in Figure 1.

Results

The next step was to refine the categories by considering how much actual historical content was to be found under each heading. Local history, visits to museums and contact with elderly people is closely related to how the national curriculum envisages that history should be taught – ‘The staff should introduce the children to people, places and institutions in the local area to create a sense of belonging’ (Kunnskapsdepartementet, 2018: 69). Since the bar was set high for Sami culture to be registered (at least a week of activities, or a description of what was involved), this category is almost certain to include at least some history. To celebrate Constitution Day is a kindergarten tradition. But only a few of the kindergartens gave the impression that they included a proper explanation of its meaning, whereby the history of the Constitutional Assembly at Eidsvoll in 1814 was likely to be covered. Museums can be artistic, scientific or cultural, of which the latter contains the most history, but whatever their content, they are always educational, and part of the local community (Barca and Pinto, 2006). Since the national curriculum envisages that history is constructed for the children through experiences locally, this category was counted among those with the highest historical content. For the same reason, interaction with elderly people was considered to convey history, even though it is unknown what topics of conversation are covered in these meetings of generations. They potentially contain at least something about the past, given that elderly people’s most active years are usually behind them. One of the five kindergartens used for research in a previous article on history at this level had a regular feature in which elderly people from the local community told the children about their own experiences of growing up (Skjæveland et al., 2013).

It should not be discounted that the remaining categories may also contain some history, but as there was not a strong presence of the categories which are more obviously historical (the largest of which, visits to museums, is represented in eight out of 63 yearly plans), it would be disingenuous to claim that there is a lot of history in categories which are neither historical per se, nor defined as such in the national curriculum. In the yearly plans, the kindergartens relate that they read fairy tales to the children, that they emphasise art and culture, or that they explore the cultures of other countries which are represented in the kindergarten. Fairy tales nearly always take place in a pre-industrial era, and children become aware of past conditions through them. Other researchers have considered fairy tales as traditional Norwegian culture containing information about the past (Moen et al., 2021; Skjæveland et al., 2013). However, based on the reading of the yearly plans, it seems that the fairy tales concerned are relatively simple, for example, ‘The Three Billy Goats Gruff’, ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ or ‘Goldilocks and the Three Bears’. These could almost be set in contemporary society. The same observation is true for religious stories belonging to Christianity, Islam and Buddhism (the three largest religions in Norway). Our reading of Buddhas Barn (Children of the Buddha) (Berg and Gaarder, 1982) uncovered only a few historical elements (mention of a sword and a sedan chair) in a book containing stories for children over about 70 pages. Art and culture are historical if they involve themes from the past. Some kindergartens also have their own library, virtually guaranteeing that books with historical content are present. In this category, however, art was represented more often than culture, and therefore it probably contains less of the past. Art is usually the vision of a single individual, while culture is something which has been incorporated into the lifeworld of a whole community, and therefore also looks to the past. Only the best artistic works become ‘timeless’, and thus conserve the life of previous generations; the remainder are forgotten.

Kindergartens are supposed to encourage learning. This means that learning about the past could potentially have a wider span than the exhortation to become familiar with local history. As the definition of learning is wide, if the staff incidentally talk about local history with the children, that is in fulfilment of the national curriculum, which asks teachers to alternate between planned and spontaneous activities. Therefore, local history and local traditions may be conveyed intuitively by those who have knowledge of the area in which the kindergarten is located. Even though such exchanges may be the most potent learning activity of all in the setting, these conversations would not be picked up in the research data (Gjems, 2011). How much of the daily lives of kindergartens comes to the fore in the yearly plans? Some go into detail about their activities, while others confine themselves to stating their pedagogical principles. However, it is thought that projects on a single theme have held a significant position in the yearly plans and, if this is still the case, history does not seem to be prioritised in the kindergartens that the research examined. The examples noted in a book about the yearly plans, ‘mountain dairy farming in Haug’ and ‘coastal culture in Vik’, are typically about local history (Alvestad, 2004: 97). In 2021, no such projects were mentioned in the yearly plans in Kristiansand.

For the last few years, I have been interested in the yearly plans as potential portals to the educational work occurring in kindergartens. Based upon what I have seen, I believe that the exceptional situation brought about by the Covid-19 pandemic had an effect on how the yearly plans were formulated. Lockdown inevitably meant that kindergartens went on fewer excursions. It is striking that the number of kindergartens mentioning visits to museums fell from 12 in 2020 to 8 in 2021, a drop of a third. The other significant development is that three historical projects were mentioned in 2020, and none in 2021. This may have been because less teaching was occurring (the staff may have been tired due to the additional burden which Covid-19 entailed), or because the need to describe routines for infection control pushed educational content out of the plans. 'I had read 70, of what were then the current yearly plans, between 9 and 13 October 2020 This was after the start of the pandemic, but as there is a time lag in what goes into the plans, the full effect had yet to emerge. This also allowed me to become familiar with previous versions, before reading the more recent plans between 16 and 18 August 2021.

A closer look at some of the kindergartens

As I was unsure how much of the actual content of the kindergartens’ activity was present in the yearly plans, I decided additionally to conduct some interviews about kindergartens in Kristiansand. These took place between 28 June and 12 August 2021, either face to face or through the audiovisual conferencing platform Zoom. The questions were prepared in advance, and supplementary questions were only asked to clarify answers which had already been given. As with the entire study, the purpose of the interviews was to uncover how much, how and where history emerged in the daily life of the kindergartens in question. A total of six interviews were conducted. The interviewees were all current or former heads of Kristiansand kindergartens, except one person who had been an assistant in one kindergarten and was now the deputy head of another. All six kindergartens concerned were among those which would have yearly plans available between 16 and 18 August 2021. Five of the interviews related to such recent conditions that they could later be compared directly with the appropriate yearly plan. Table 1 summarises which categories the yearly plans describe, while Table 2 shows the categories that I understood were present in the kindergarten after conducting the interview. A cross marks the presence of that particular content.

Possible historical content according to the yearly plans

| Yearly curriculum | Local history | Sami culture | Constitution Day | Museum | Concepts of time | Traditional games | Religion | The elderly | Fairy tales | Art and culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X | X | X | X | X | |||||

| 3 | X | X | ||||||||

| 4 | ||||||||||

| 5 | X | |||||||||

| 6 | X | X | X |

Historical content according to interview

| Interview | Local history | Sami culture | Constitution Day | Museum | Concepts of time | Traditional games | Religion | The elderly | Fairy tales | Art and culture |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||

| 3 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 4 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 5 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 6 | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

It is not surprising that there are far more crosses for the interviews, as the teachers were asked directly whether this content was present in their kindergarten. On the basis of the interviewee’s answer, a cross was placed if what was said was extensive enough both to be certain that the content was present and that it involved historical elements (broadly defined). Some interviews indicated the absence of historical content. For example, regarding concepts of time: ‘The children often don’t understand concepts of time. They say things like “they were in the zoo tomorrow”, or “they are going there yesterday”. These mistakes are unobtrusively corrected by the staff. They do not introduce children to the calendar.’ This answer does not seem to indicate a particular focus on concepts of time. The concepts are instead learned spontaneously. Compared to the more extensive responses of other interviewees, no cross was marked for concepts of time for this kindergarten. Regarding religion: ‘Very few religious stories were used. The Gospel for Christmas was read. It was not emphasised. It was said that it had happened a very long time ago.’ This answer gives the impression that the content was hardly present. It should be noted that the absence of a category must not be regarded as criticism. As mentioned, kindergartens are asked to alternate between planned and spontaneous activities. It is just as correct to cover these categories on an incidental basis, while some are not required at all. For the purposes of the study, however, it was especially planned content which led to a category being marked as present.

As for the yearly plans, these are examples of historical content being present. Regarding museums: ‘The kindergarten mentions five local institutions as partners, of which one is a museum and one is a library [which normally has exhibitions].’ Regarding art and culture, including Sami culture: ‘Projects like “Sami week” and “the cultural café” … we convene a cultural café.’

The category ‘art and culture’ had fewer crosses in the interviews than in the yearly plans, because there was no interview question directly related to this category. By the time the interview questions were formulated, it was clear that ‘art and culture’ had been an ‘also-ran’ category, containing little historical content in a kindergarten context. (An exception was one kindergarten which had considered the lives of famous artists.) There was correspondence between the interviews and the yearly plans in nine cases (with crosses in both Table 1 and Table 2), where there could potentially have been 41.

It can be demonstrated mathematically that the content which was found through reading the yearly plans and the content which was uncovered by interview only overlapped a little. Using set theory results in an intersection between the two of just over 20 per cent. Even if questions about the category ‘art and culture’ had been asked in the interviews, intersection could still not have reached 26 per cent. In other words, the vast majority of what occurs in the kindergartens does not make it into the yearly plans. In addition, it was discovered through the interviews that five of the six kindergartens had undertaken projects which were either directly historical or which resembled the local projects mentioned by Alvestad (2004). One of the kindergartens had arranged a visit by a local historian. Another had invited a well-known local character, who told the children a lot about her personal reminiscences of ‘bygone days’. It is worth keeping in mind, however, that the interviewees were not asked to distinguish between what had occurred recently and what had taken place many years ago. This is one of the reasons why more historical content was found through interview. At the same time, it became clear that local history, Sami culture, Constitution Day with historical elements, traditional games and religious stories form part of the content every year, and thus could have been mentioned in any yearly plan.

Discussion

After conducting the interviews, I reached a better understanding of how adept the categories had been at catching historical content. Socialisation with elderly people turned out to contain much less history than I had originally believed. None of the kindergarten teachers thought that there had been much talk of past times during such encounters, nor had they set out to encourage this. Local history, visits to museums and the projects are the categories which contain the most history (although, as discussed, the category ‘projects’ had to be removed from the survey). The kindergartens teach local history all the time, go on visits to museums regularly, and establish projects in which history is an element from time to time. Constitution Day, Sami culture and what was used of religious stories also contain a modicum of history. The kindergarten teachers seem to be skilled at setting events under these headings in context as occurring ‘long ago’. As for fairy tales, I got the impression that the kindergartens considered any traditional story for children to fall under this heading. Only one of the interviewees mentioned the folk tales of Asbjørnsen and Moe specifically. It is thus not certain that this piece of Norwegian cultural history is routinely present in the kindergartens. Concepts of time and traditional games, as well as art and culture, are potentially historical, but in practice they seemed to be taught independently of any historical content. Table 3 summarises my considered opinion of the original categories.

Content and historical presence

| Presence of history | Categories |

|---|---|

| High | Local history, museums, projects |

| Medium | Constitution Day, Sami culture, religion |

| Low | Concepts of time, traditional games, the elderly, fairy tales, art and culture |

Reading the yearly plans did go some way towards estimating the extent to which history is present in the kindergartens of Kristiansand. Nevertheless, the plans range from 8 to 50 pages in length, and it is obvious that the more they say about the kindergarten, the more crosses could be marked on the form. The interviews gave significantly more information, and they led to the conclusion that local history, visits to museums and occasional projects involving history are relatively common in kindergartens in this locality. The same is true for the categories with the second-highest historical content: Sami culture, Constitution Day celebrations and religious stories. These findings primarily emerged from the interviews, with the yearly plans helping to provide a wider picture. The presence of large amounts of information usually meant that the kindergarten had significant educational content. This correlates to the presence of history, but the kindergartens which are more reticent in their yearly plans may still be involved in plenty of activities. One kindergarten which was later registered with no content at all on the basis of its yearly plan was found in the interview to visit museums, teach local history and occasionally run projects which are historical.

Educational content is more widespread in private kindergartens which are public limited companies, those which purchase resources from others and, locally, those which were connected to the Agder Project (a funded project on ‘playful learning’ run by two universities between 2014 and 2018) (Dahle, 2020). Probably the only kindergartens which go beyond what is required by the national curriculum are those which have specifically chosen to make history a priority. Most of the previous research on history in the kindergarten has consisted of reports about what such projects achieved.

Future directions

Since the literature is clear about the many benefits that learning history has for preschool children, new schemes might be developed in individual kindergartens. The first monograph about history at this level in Norway was by Moen et al. (2021). It may provide impetus towards making wider use of local historical pedagogy, which in any case is encouraged in the Framework Plan. More studies like the present one, considering the situation in various parts of the country, would be helpful to gather data about the role that history, broadly understood, already has. It is an intuitive and enjoyable subject for many young learners. Over time, giving it more attention in kindergartens may even bolster its place in schools, where it has been downgraded for several decades, even though history offers much-needed perspectives for society (Guldi and Armitage, 2014). On an international level, this article has considered whether it is possible to teach history orally and informally to a preschool age group. As it was found to be possible in theory, the extent to which this actually takes place in the locality is of some interest.

Conclusion

On the basis of the yearly plans and the interviews, I believe that there is some exposure to history in the kindergartens of Kristiansand. This is the same result as was found in the most closely related investigation, about another Norwegian city, Trondheim (Moen and Buaas, 2012). Kindergartens follow the national curriculum in concentrating upon local history in general. When historical projects are underway, these also tend to concentrate on local affairs. The focus on the local area makes past events more comprehensible and real for children. The research found that a higher level of abstraction leads to lower historical content. National (or sometimes international) history is more prevalent when teaching Constitution Day, Sami culture and religious stories, but when this material is used, the presence of history is lower than for local history and projects. The one exception to this pattern is that museums were judged to have a high presence of history, and they are nationally, rather than locally, oriented.

In general, as the level of abstraction becomes yet higher, as with concepts of time, traditional games, fairy tales, and art and culture, the presence of history diminishes further. It may be harder for kindergarten teachers to detect the presence of history in these categories. Social interaction with elderly people is envisaged as conveying local history in the national curriculum. However, this investigation indicated that this did not happen. Reasons mentioned in the interviews include that there were few opportunities for conversation, that no scope was given for talking about the past, that the elderly people seemed tired and out of sorts, and that contact was limited to the grandparents of the children, who were still in work and not particularly interested in the past.

Only the categories described as having a ‘high’ presence of history are certain to exceed the level of historical content inherent in everyday activities and conversations. As these categories are also mostly connected to the local environment, it would be accurate to say that history does not appear in kindergartens beyond what is envisaged in the national curriculum. Although few kindergartens mention local history in their yearly plans, the six interviews conducted all led to the conclusion that local history was present in the particular institution. On this basis, I assume that most kindergartens in Kristiansand include elements of local history in their teaching. The conclusion about the presence of history in those kindergartens is therefore that it is of a local kind, and that it is taught through excursions and activities around the kindergarten, as well as informally. There are also occasional projects where teaching is intensified. This confirms the presence of the subject, but not what the learning outcomes are. The consensus in the literature is that there are substantial benefits for the children when there is a particular emphasis on history in a kindergarten. In other institutions with just an ordinary presence of the subject, the learning outcomes probably depend upon whether the teaching replicates the techniques described in reports of successful projects. The question is ultimately tied up with the debate noted in the introduction between supporters of ‘playful’ learning (Sommer, 2018), and those who believe that informal learning is less advantageous than systematic instruction (Levstik and Thornton, 2018).

Acknowledgments

Arve Hansen provided very useful advice in the initial stage of researching this article. Laura Arias, Kirsten Horrigmo and Helena Pinto helped with suggestions for literature. The advice of the two anonymous referees for this journal improved the article. The six interviewees made the results much more significant. Earlier versions of the article were discussed in the social science education research group at the University of Agder.

Declarations and conflicts of interest

Research ethics statement

The author declares that research ethics approval for this article was provided by the Norwegian Centre for Research Data (Reference Number 416239).

Consent for publication statement

The author declares that research participants’ informed consent to publication of findings – including photos, videos and any personal or identifiable information – was secured prior to publication.

Conflicts of interest statement

The author declares no conflicts of interest with this work. All efforts to sufficiently anonymise the author during peer review of this article have been made. The author declares no further conflicts with this article.

References

Alvestad, M. (2004). Årsplanarbeid i Barnehagen. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Arias-Ferrer, L; Egea-Vivancos, A; Levstik, L.S. (2019). ‘Historical thinking in the early years: The power of image and narrative’. Story in Children’s Lives: Contributions of the narrative mode to early childhood development, literacy, and learning. Kerry-Moran, K.J, Aerila, J.-A J.-A (eds.), Cham, Switzerland: Springer, pp. 175–98.

Askeland, N; Maagerø, E. (2011). ‘Fagspråk i barnehagen. Fra riddere til gravemaskiner’. Barns Læring om Språk og Gjennom Språk: Samtaler i Barnehagen. Gjems, L, Løkken, G G (eds.), Oslo: Cappelen Damm, pp. 119–47.

Barca, I; Pinto, H. (2006). ‘How children make sense of historic streets: Walking through downtown Guimaraes’. International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research 6 (1) : 2–9, Accessed 16 May 2023. https://www.history.org.uk/publications/categories/304/resource/4861/the-international-journal-volume-6 . DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18546/HERJ.06.0.02

Barton, K.C; Levstik, L.S. (2008). ‘“Back when God was around and everything”: Elementary children’s understanding of historical time’. Researching History Education. Levstik, L.S, Barton, K.C K.C (eds.), New York: Routledge, pp. 71–107.

Berg, A.-M; Gaarder, I.M. (1982). Buddhas Barn. Oslo: Cappelen.

Bøe, J.B. (1999). Barnet og fortellingen: Fortidsfortellingens innflytelse på barnets historiebevissthet. Kristiansand: Høyskoleforlaget.

Boldt, A. (2014). ‘Ranke: Objectivity and history’. Rethinking History 18 (4) : 457–74, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2014.893658

Cooper, H. (1994). ‘History 5–11’. Teaching History. Bourdillon, H (ed.), London: Routledge, pp. 76–86.

Cooper, H. (2013). History in the Early Years. 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

Dahle, H.F. (2020). ‘Barns rett til lek og utdanning i barnehagen’. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Pedagogikk & Kritikk 6 : 100–14. Accessed 14 May 2023. https://pedagogikkogkritikk.no/index.php/ntpk/article/view/2055/4211 .

De Groot-Reuvekamp, M; Ros, A; Van Boxtel, C; Oot, F. (2017). ‘Primary school pupils’ performances in understanding historical time’. Education 3–13 45 (2) : 227–42, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2015.1075053

Dingstad, P. (2012). ‘“Åttetoget til Tokyo”. Praktisk arbeid med nærmiljø og samfunn i barnehagen’. Barnehagelærerutdanningens kompleksitet: Bevegelser i faglige perspektiver. Otterstad, A.M, Rossholt, N N (eds.), Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, pp. 290–313.

Edwards, C. (2008). ‘The how of history: Using old and new textbooks in the classroom to develop disciplinary knowledge’. Teaching History 130 : 39–45. Accessed 14 May 2023. https://www.history.org.uk/publications/resource/1051/the-how-of-history-using-old-and-new-textbooks-in .

Evjen, B. (2009). ‘Research on and by “the Other”: Focusing on the researcher’s encounter with the Lule Sami in a historically changing context’. Acta Borealia 26 (2) : 175–93, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08003830903372076

Fønnebø, B; Jernberg, U. (2018). Barnehagens rammeplan i praksis – ledelse, omsorg og kompleksitet. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

Gjems, L. (2007). Hva lærer barn når de forteller? Barns læringsprosesser gjennom narrativ praksis. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Gjems, L. (2011). ‘Hverdagssamtalene – barnehagens glemte læringsarena?’. Barns læring om språk og gjennom språk. Samtaler i barnehagen. Gjems, L, Løkken, G G (eds.), Oslo: Cappelen Damm, pp. 43–67.

Gray, P. (2011). ‘The decline of play and the rise of psychopathology in children and adolescents’. American Journal of Play 3 (4) : 443–63. Accessed 16 May 2023. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265449180_The_Decline_of_Play_and_the_Rise_of_Psychopathology_in_Children_and_Adolescents .

Guldi, J; Armitage, D. (2014). The History Manifesto. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hammer, S. (2017). Foucault og den norske barnehagen: Introduksjon til Michel Foucaults analytiske univers. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Harnett, P. (2007). ‘Teaching emotive and controversial history to 3–7 year olds: A report for the Historical Association’. International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research 7 (1) : 1–24, Accessed 16 May 2023. https://www.history.org.uk/publications/categories/304/resource/4862/the-international-journal-volume-7-number-1 . DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18546/HERJ.07.1.05

Harris, R; Graham, S. (2019). ‘Engaging with curriculum reform: Insight from English history teachers’ willingness to support curriculum change’. Journal of Curriculum Studies 51 (1) : 43–61, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1513570

Horrigmo, K.J. (2014). Barnehagebarn i nærmiljø og lokalsamfunn: Fagdidaktikk – aktiviteter og opplevelser. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Jalongo, M.R. (2019). ‘Personal stories: Autobiographical memory and young children’s stories of their own lives’. Story in Children’s Lives: Contributions of the narrative mode to early childhood development, literacy, and learning. Kerry-Moran, K.J, Aerila, J.-A J.-A (eds.), Cham, Switzerland: Springer, pp. 11–28.

Jensen, B.E. (1994). Historiedidaktiske Sonderinger. Copenhagen: Danmarks Lærerhøjskole. Vol. 1

Johanson, L.B. (2015). ‘The Norwegian curriculum in history and historical thinking: A case study of three lower secondary schools’. Acta Didactica Norge 9 (1) : 1–24, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5617/adno.1301

Jordanova, L. (2019). History in Practice. 3rd ed. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Kaplan, M. (2003). ‘On the road to realism with Asbjørnsen and Moe, “Peer Gynt”, and Henrik Ibsen’. Scandinavian Studies 75 (4) : 491–508. Accessed 14 May 2023. http://www.online-literature.com/article/ibsen/1087/ .

Kjeldstadli, K. (2013). Fortida er ikke hva den en gang var: En innføring i historiefaget. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Korsvold, T. (2016). Perspektiver på barndommens historie. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

Kunnskapsdepartementet. (2018). ‘Forskrift om rammeplan for barnehagens innhold og oppgaver’. Lovdata, Barnehageloven med forskrifter. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget, pp. 49–69.

Levstik, L.S; Thornton, S.J. (2018). ‘Reconceptualizing history for early childhood through early adolescence’. The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. Metzger, S.A, Harris, L.M L.M (eds.), New York: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 473–501.

Likestillingssenteret. (2010). Nye barnehager i gamle spor? Hva vi gjør, og hva vi tror. Status for likestillingsarbeidet i norske barnehager 2010. Accessed 16 May 2023. https://www.udir.no/globalassets/upload/barnehage/forskning_og_statistikk/rapporter/nye_barnehager_i_gamle_spor_2010.pdf .

Lund, E. (2020). Historiedidaktikk: En håndbok for studenter og lærere. 6th ed. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Mathis, C; Parkes, R. (2020). ‘Historical thinking, epistemic cognition, and history teacher education’. The Palgrave Handbook of History and Social Studies Educatio. Berg, C.W, Christou, T.M T.M (eds.), Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 189–212.

Moen, K.H; Buaas, E.H. (2012). ‘Historie og tradisjonsformidling i barnehagen – en utrendy utfordring?. FoU i praksis 2011: Rapport fra konferanse om praksisrettet FoU i lærerutdanning. Rønning, F, Diesen, R; R and Hoveid, H; H, Pareliussen, I I (eds.), Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag, pp. 225–36.

Moen, K.H; Buaas, E.H; Skjæveland, Y. (2021). Det var en gang… Historie og tradisjoner i den flerkulturelle barnehagen. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Myrstad, A. (2021). ‘Samiske perspektiver i en barnehages hverdagsliv’. Fagdidaktikk for SRLE: Barnehagens fagområder, kunnskapsgrunnlag og arbeidsmåter. Horrigmo, K.J, Rosland, K.T K.T (eds.), Oslo: Cappelen Damm, pp. 202–14.

Nichol, J; Dean, J. (2003). ‘Writing for children: History textbooks and teaching’. International Journal of Historical Learning, Teaching and Research 3 (2) : 53–81, Accessed 16 May 2023. https://www.history.org.uk/publications/categories/304/resource/4856/the-international-journal-volume-3-number-2 . DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18546/HERJ.03.2.05

Nitsche, M; Mathis, C; O’Neill, D.K. (2022). ‘Editorial: Epistemic cognition in history education’. Historical Encounters 9 (1) : 1–10, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52289/hej9.101

Nordstrand, A.W; Karsrud, F.T. (2014). ‘Sted, fortelling og literacy: Om sammenhengen mellom sted, kultur og barns læring og språkutvikling’. Barn 32 (2) : 51–69, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5324/barn.v32i2.3485

Østrem, S; Bjar, H; Føsker, L.R; Hogsnes, H.D; Jansen, T.T; Nordtømme, S; Tholin, K.R. (2009). Alle teller mer: En evaluering av hvordan Rammeplanen for barnehagens innhold og oppgaver blir innført, brukt og erfart. Tønsberg: Høgskolen i Vestfold.

Paxton, R.J. (1999). ‘A deafening silence: History textbooks and the students who read them’. Review of Educational Research 69 (3) : 315–39, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543069003315

Pedersen, P; Høgmo, A. (2012). Sapmi slår tilbake: Samiske revitaliserings- og moderniserings-prosesser i siste generasjon. Karasjok: CalliidLagadus.

Pinto, H; Ibanez-Etxeberria, A. (2018). ‘Constructing historical thinking and inclusive identities: Analysis of heritage education activities’. History Education Research Journal 15 (2) : 342–54, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18546/HERJ.15.2.13

Raugland, V. (1996). Grunnskoleloven. (Lov om grunnskolen av 13. juni 1969 nr. 24). Med endringer senest av 16. juni 1995 nr. 28. (Uten endringene fra 1997). Oslo: Ad notam Gyldendal.

Saabye, M. (). (n.d.). Læreplanverket for Kunnskapsløftet 2020: Grunnskolen. Oslo: Pedlex.

Skjæveland, Y. (2017). ‘Learning history in early childhood: Teaching methods and children’s understanding’. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 18 (1) : 8–22, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1463949117692262

Skjæveland, Y; Buaas, E.H; Moen, K.H. (2013). ‘Danning gjennom historie og tradisjonsformidling i barnehagen’. FoU i praksis 2012: Conference Proceedings. Pareliussen, I, Moen, B.B; B.B and Reinertsen, A.B; A.B, Solhaug, T T (eds.), Trondheim: Akademika, pp. 240–48.

Sommer, D. (2015). ‘Tidlig skole eller lekende læring? Evidensen for langtidsholdbar læring og utvikling i barnehagen’. Læring, dannelse og utvikling: Kvalifisering for fremtiden i barnehage og skole. Klintmøller, J, Sommer, D D (eds.), Oslo: Pedagogisk Forum, pp. 65–85.

Sommer, D. (2018). Utvikling: Fra utviklingspsykologi til utviklingsvitenskap. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget.

Statistisk Sentralbyrå. (2021). Fakta om utdanning 2021 – nøkkeltall fra 2019. Oslo: Statistisk Sentralbyrå.

Sundsdal, E; Øksnes, M. (2015). ‘Til forsvar for barns spontane lek’. Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk & kritikk 1 : 1–11, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17585/ntpk.v1.89