Introduction: the issue

History can be experienced in different ways. In history education, students largely experience history through teachers’ narratives, textbooks and other types of teaching resources (Berg, 2021; VanSledright, 2011). However, students occasionally get the opportunity to encounter history and the past outside the classroom walls through visits to museums and historical sites. In Sweden, this article’s educational context, the idea that students should visit local and regional historical sites is a firmly rooted tradition dating back to the beginning of the twentieth century (Rantatalo, 2002). It has been suggested that the reasoning behind such visits may be that they afford students the opportunity to experience the past from a perspective that the classroom cannot offer (Ludvigsson et al., 2021; Stolare et al., 2021).

A relatively new destination for study trips within the Swedish educational system is the concentration and extermination camps at Auschwitz-Birkenau in southern Poland. Almost one-third of all Swedish municipalities employ staff to take students studying history, religious studies or social sciences at the secondary level on trips to Holocaust sites (Flennegård, 2018). However, Sweden is by no means a special case, as these kinds of trips are part of many other European countries’ curricula (FRA, 2011; Nesfield, 2015).

We want to place this article within the history education research field by examining the role that visits to historical sites can play in history education – or, more specifically, the historical experiences that such visits make possible and how students express these in their subsequent historical interpretations and ‘orientation’ (Rüsen, 2008). Taking a field trip to a nearby medieval ruin is one thing, but visiting a Holocaust site is something else entirely. These places have a special historical–cultural significance, and for those who visit them, they can be complex environments in which the dimensions of ‘learning about’ and ‘learning from’ are combined (Cowan and Maitles, 2011). Holocaust sites have a present and future relevance that points to the orienting potential of teaching-embedded site visits. According to Flennegård and Mattsson (2021), despite extensive studies on both teaching about the Holocaust and on school trips to Holocaust sites, relatively little research has been conducted on students’ experiences during their visits to Holocaust sites, as well as these visits’ potential impact on students’ learning and historical orientation.

This article concerns a class of upper-secondary school students from Sweden who visited the Holocaust site Auschwitz-Birkenau as part of their history and religious education courses. The empirical data comprised transcripts of audio recordings from two seminars that were part of the examinable work that students completed after their return from the school trip. The article aims to analyse how different forms of historical experience (cognitive, affective and physical) acquired during visits to historical sites – in this case, Auschwitz-Birkenau – interact within students’ expressed historical orientation. For our analysis, we sought to answer two research questions:

-

What forms of experience do students express, and how do these forms relate to each other?

-

What implications might these expressed experiences pose for how teachers organise their teaching, including trips to Holocaust memorial sites?

These questions will be discussed in relation to each other using a model that Zachrich et al. (2020) have developed. This model captures how an encounter with complex historical sources, such as a visit to a historical site, can result in cognitive, affective and physical experiences. It also seeks to demonstrate how these different forms of experience can be related. The article aims to test Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model empirically, and in so doing, contribute to the discussion around the educational role that visits to historical sites can play in history education.

Previous research

This study is conducted in relation to two different, yet related, research fields. One concerns research on Holocaust sites as an element of teaching about the Holocaust. The second, which is more relevant to this article, concerns visits to museums and historical sites, and the role that they play in history education.

Extant research has indicated that Holocaust sites are complex places with different roles and functions that operate in tandem (Richardson, 2021). It has been suggested that the emotional experiences that accompany visits to such sites can hinder students’ learning; however, the interplay between the cognitive, affective and physical dimensions of students’ historical experiences in authentic learning contexts has not been explored fully yet (Flennegård and Mattsson, 2021; Nesfield, 2015). In research investigating visits to museums and historical sites, as well as the role that these sites play in teaching, questions about students’ varying historical experiences are featured more prominently (see Marcus, 2007; Rohlf, 2015; Savenije et al., 2014; Spalding, 2011). It has been noted that the character of the narratives that students encounter during these visits is important, particularly the extent to which the narratives are either ‘open’ or ‘closed’; that is, the extent to which they give students the opportunity to relate to them. A more open narrative that offers multiple points of entry can create opportunities for students from different backgrounds to connect with the narrative, display or historical site itself (Savenije and de Bruijn, 2017; Savenije et al., 2014). It has also been demonstrated that students can gain a deep historical understanding by visiting museums and historical sites because of the opportunity that they have to experience historical artefacts (Levstik et al., 2014; Marcus and Levine, 2011).

The contextual and cognitive dimensions have been somewhat overshadowed in educational museum research. Instead, a greater emphasis has been placed on the importance of historical objects and exhibitions as a means of contributing to learning by arousing emotions in students. It has also been noted that visits to museums and historical sites enable interaction between the cognitive and affective dimensions of historical empathy, particularly when it comes to sensitive and potentially controversial issues (Savenije and de Bruijn, 2017; Trofanenko, 2011, 2014). By relating such findings to, among other things, psychological research, Endacott and Brooks (2013) have further developed the concept of historical empathy. They emphasise the importance of linking cognitive and affective experiences, and that these experiences should be viewed as integral dimensions of historical empathy (Endacott and Brooks, 2013; see also Bartelds et al., 2020; Brooks, 2008). Simultaneously, as indicated above, extant research has noted that museum exhibitions can stimulate the role that materiality and embodiment play in students’ encounters with the past (Witcomb, 2013).

Theoretical foundations: learning history by experiencing remnants of the past

As mentioned above, one argument for incorporating visits to museums and historical sites into history education is their potential to provide students with a first-hand – and, thus, direct – encounter with remnants of the past. To be able to see, touch, feel and smell artefacts provides a special opportunity for the construction of historical understanding (Marcus and Levine, 2011). Zerubavel (2003) has supported this idea by arguing that historical places, with their associations and artefacts, can connect individuals to the past. This reasoning points to the emotional role that visits to historical sites can play in the history classroom.

Simultaneously, the experience of a visit to a historical site, and students’ encounters with physical remnants of the past, depends on how the visit is organised. Will the visit be an opportunity for students to ‘live’ the place, or will it be experienced as simply an extension of teaching resources and methods that they would normally encounter during their lessons? The former would mean that they experience an Erlebnis – that is, an encounter with remnants of the past that is subjective, bodily and direct (Arthos, 2000; Gadamer et al., 2004; Tapper, 1925) – while the latter would mean that they experience an Erfahrung – that is, a more socially inflected encounter, in which drawing conclusions and cognitive learning are central (Carr, 2014). The interplay between (the difficult-to-translate concepts) Erlebnis and Erfahrung – as two ways of encountering and experiencing remnants of the past – could be important in the context of the history classroom. Neither is better than the other, but each offers a different, yet complementary, way to learn history.

Much of history education research has taken a cognitive approach, with a strong emphasis on how students can acquire the tools necessary for thinking about history, and how they can develop and use ‘second-order concepts’ (Lee and Shemilt, 2003; Seixas, 2017). This approach generally has been ambivalent towards the role that historical empathy might play in history teaching (Davis et al., 2001). However, a notable change has occurred in recent years (Endacott and Brooks, 2018), one that has been clearer outside the area of history education research. In the broad field of social sciences, there has been talk of an affective turn (Wetherell, 2012), that is, awareness of the body and a non-dualistic approach to human experience have become more prominent. It has been acknowledged that bodily responses are important elements of visits to historical sites (McKernan, 2018). While this study seeks to relate to the growing body of affective research, it also recognises that the cognitive perspective is necessary. Opportunities for students to experience remnants of the past as both Erfahrung and Erlebnis are important in history education.

Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model connects to the discussion above because it attempts to balance the cognitive and affective dimensions of learning history with a third dimension: the physical. Using theoretical and empirical research as their foundation, they have constructed an analytical framework to characterise human responses to encounters with historical artefacts and places. In this article, we use Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model to analyse the data that we collected on students’ retrospective reflections after a school trip to a Holocaust memorial site (see the ‘Empirical data and analysis’ section below).

Method

The empirical starting point in a thematic teaching unit

This article is based on empirical data collected in conjunction with a thematic teaching unit developed jointly by Swedish history teachers and researchers (Berg) to enable students at the upper-secondary level (ages 15–18) to investigate the Holocaust as a historical phenomenon. The students in this study were 18 years old and in the final year of upper-secondary school. They were enrolled in a course designed to prepare young adults for university studies in social sciences. The students studied the Holocaust unit for seven weeks (between February and March 2016). During the fourth week of the unit, the students went on a school trip to the former concentration camp at Auschwitz. After they returned, what they learned from this unit was examined by participating in a seminar (hereafter called an examinable seminar). The findings in this article are based on transcripts of seminars held with two different groups of students.

The examinable seminars were held during normal teaching time in the students’ usual classrooms, and data collection was conducted based on guidelines that apply to other similar studies. Informed consent was obtained after the purpose of the study, and the voluntary nature of their participation was explained to each group. Because it was a seminar, care was taken to ensure that the students participated only if they felt comfortable doing so (see Berg, 2021); therefore, it was important to ensure the participants’ anonymity. In this case, conversational details that could connect the speaker to a specific person or place, or lead to their identification by some other means, were removed during transcription (see Persson and Berg, 2022). Digital materials were saved on password-protected computers. An important part of ethical research practice is also to ensure that the analysis is conducted ethically in relation to the empirical evidence. Therefore, this article adopted a robust theoretical framework and thoroughly tested its results.

As Table 1 indicates, the teaching time of this unit was divided between the four weeks prior to the school trip, during which 36 hours were devoted to classroom teaching, and the two weeks after the trip, during which 18 hours were used, mainly for post-processing and examination. This unit was shared between the subjects of history and religious education, comprising part of Swedish secondary schools’ History 3 and Religious Education 2 curriculum. (History 3 is the third of three and Religious Education 2 the second of two courses that students on an ‘academic’-track social sciences programme take during their upper-secondary school years in Sweden.) Therefore, teaching had to be planned in accordance with the syllabuses for both subjects.

Teaching hours for the course unit ‘The Holocaust as an Object of Study’

| Weeks | History 3 | Religious Education 2 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 weeks before the school trip | 24 hours | 12 hours | 36 hours |

| 2 weeks after the school trip | 12 hours | 6 hours | 18 hours |

| Total | 36 hours | 18 hours | 54 hours |

The Swedish upper-secondary school history curriculum does not mention the Holocaust as a specific content, but it does have stated objectives that can be used to support studying it. Furthermore, in Swedish educational documentation that discusses the basic values that education should promote, nothing requires that teaching should focus specifically on the Holocaust. That said, it is possible within the frameworks of the history and religious education curricula to work with the Holocaust as an subject of study. The Holocaust unit emerged from the objective within the history curriculum that states that teaching should be related to ‘an example of change that occurred on a global scale during the 19th and 20th centuries, its factual progress and consequences for society, groups and individuals at the regional or local level’ (Skolverket Lgy, 2011: n.p.). Furthermore, the teaching content was developed because it addressed, also in the words of the curriculum, a ‘source-critical and methodological problem associated with the treatment of different types of historical source material in, for example, political history, social history or environmental history’ (Skolverket Lgy, 2011: n.p.). In addition to these points in the history curriculum is the unit designed to address questions about ethics and interpersonal relationships, which forms part of the religious education curriculum.

The three components of the thematic unit

The delivery and teaching of the thematic unit were divided into three stages. After the idea of a trip was introduced to the students, a discussion was conducted about how it was going to be organised. The students had the opportunity to voice their opinions about which thematic areas they thought would be interesting to work on ahead of the trip. During the remaining preparatory time, the focus was on preparing the selected themes (see Figure 1).

The second part of the programme involved a visit to Auschwitz. The journey began with a walking tour of Krakow that focused on the historical relationship between the city’s Jewish and non-Jewish communities. Next, the students were taken on a guided tour of the Auschwitz complex, comprising over 40 different camps and other structures. The students visited two locations: one known as Auschwitz I and the other comprising Auschwitz II and Birkenau. During the trip, which lasted approximately three hours, the guide provided detailed information about the physical locations and events associated with the site.

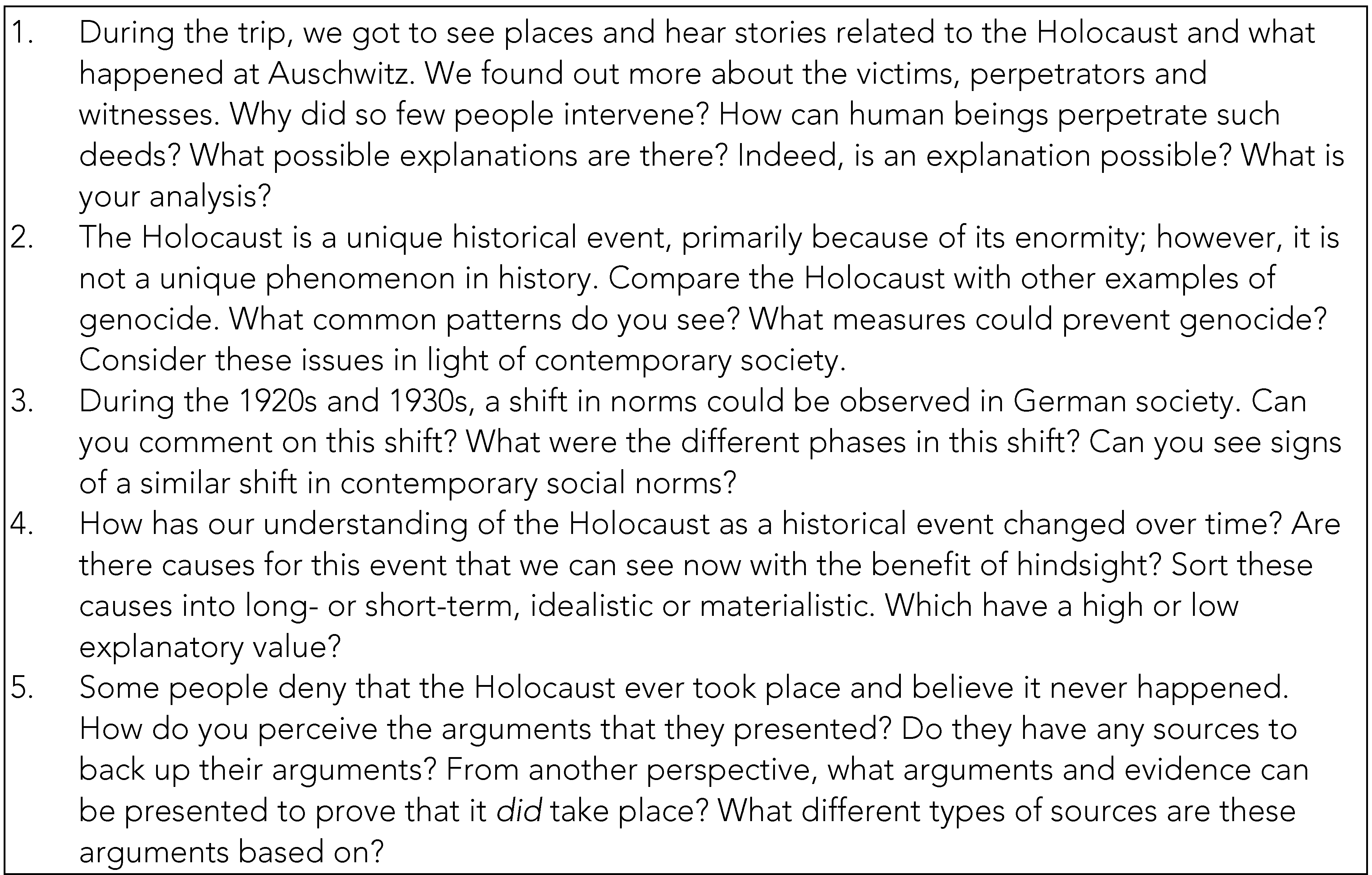

During the thematic unit’s third and final stage, after the students returned to Sweden, the students’ experiences from the trip were processed in light of the themes that had been the focus prior to departure. This connection also characterised the final assessment of the unit, namely the examinable seminar. Students were divided into two seminar groups, and their seminars were conducted three weeks after returning from the study trip. Group 1 comprised six students, and Group 2 comprised four. The teacher and researcher who had been on the trip with the students led each group’s seminar. The seminars were held in the students’ regular classroom and lasted about 60 minutes each. The teacher and researcher managed the discussion, ensuring its progression and asking additional questions as needed. The purpose of the discussion was to combine the knowledge and understanding that the students had learned prior to the trip with the experiences they gained during the trip. The seminars focused on a specific set of questions related to the theme, and the teachers formulated the questions beforehand, and linked them to the syllabus.

Empirical data and analysis

As indicated, the transcripts of the audio recordings of the two examinable seminars comprise this article’s empirical material. The content of the seminar questions (see Figure 2) and the discussion that followed them should be viewed as the school acting as an authoritative body to determine both the curriculum and, by extension, teaching content. The focus of the curriculum explains why most of the questions aim to develop students’ understanding of the processes that encompass the Holocaust as a historical phenomenon. Therefore, the questions regularly used terms such as ‘explanations’, ‘analysis’, ‘causes in the long and short term’, ‘arguments’ and ‘sources’. The questions also demanded a large measure of contextualisation of the Holocaust as a historical phenomenon by obliging students to relate it to other historical periods and phenomena. Therefore, the questions emphasised what could be described as disciplinary knowledge and a cognitive approach to historical knowledge. Notably, this study was conducted within a school setting, in which competing priorities may have been present; that is, the school context probably influenced the students’ understanding of history. What they said during the seminar also needs to be viewed as part of how they chose to respond to the requirements of an examinable assessment. It also must be considered that participating teachers and researchers were present during both the study visit and the final seminar. Our analysis aimed to link our findings to a dynamic understanding of place. Places are created through interaction (Smith, 2021). With this starting point, a sense of place is also created during the seminars when different types of experiences interact. This process of experience, interpretation and historical orientation comprises the object of inquiry of the study.

The analysis of the seminar transcripts was based on Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model, and it is presented in Table 2. The model identified three dimensions of the response to a historical site: cognitive, affective and physical.

Zachrich et al.’s model of students’ interaction with and response to a historical site (Source: Zachrich et al., 2020)

| Dimension | Response | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Attentional focus | Learners concentrate deeply on the encounter with the source. | ‘I did not even notice anything around me while interacting with the source.’ |

| Imagination | Learners create a mental image or envision a particular version of the information presented by the source. | ‘I could imagine, exactly, how the place looked 100 years ago’, or ‘I could picture the scene the eyewitness talked about.’ | |

| Perspective recognition | Learners understand the view of the historical agent (the eyewitness or a person who was involved with the site). | ‘I understand why the historical agent who spent time at this place felt and acted that way’, or ‘I totally understood the eyewitness’s thoughts and feelings.’ | |

| Contextualisation | Learners link the displayed information to their prior knowledge about the historical time/place/events. | ‘When I think of the circumstances the people had to deal with during that time, their actions become even more courageous.’ | |

| (Sense of) insight | Learners believe they have a better understanding about the past because of new information/perception gained from experience with the source. | ‘I know better now what post-war life must have been like.’ | |

| Affective | Being moved | Learners are emotionally touched by the information that the source conveys. | ‘The object in the exhibition moved me’, or ‘The story of the eyewitness deeply touched me.’ |

| Personal attachment | Learners identify with the historical agent through a personal connection or perception of the story from their point of view. | ‘The historical agent’s story reminded me of my grandmother’, or ‘I could feel the feelings of the eyewitness myself.’ | |

| Awe and reverence | Learners feel a deep appreciation for the historical agent and a connection bigger than themselves. | ‘My God, when you think of what they went through.’ | |

| Historical proximity | Learners feel a spatial and temporal closeness to the past. | ‘The past became vivid.’ | |

| Irritation | Learners have a feeling of irritation because of unexpected or conflicting information. | ‘I was not expecting that’, or ‘I always thought it was different.’ | |

| Physical | Physiological response | Learners react to the complex sources with involuntary bodily responses. | ‘Being at the site gave me an uncomfortable feeling in my stomach’, or ‘The story gave me goosebumps.’ |

| Sensory interaction | Learners perceive the elements of the complex sources within an interplay of their senses. | ‘I could smell the eyewitness’s perfume’, or ‘The museum felt cold and dark.’ | |

| Physical interaction | Learners physically move through the site and/or have a conversation with the eyewitness. | ‘I walked the same way xyz did’, or ‘I felt I could get answers to my very personal questions.’ |

The categories that Zachrich et al. (2020) formulate should be viewed as theoretical and not tested empirically. In that respect, their validity can be discussed. In this article, we did not use these categories as a theoretical starting point for analysing the empirical evidence. Instead, the approach can be described as abductive, in that we derived our findings for our analysis from an interaction between theory and practice. In this way, the methodology adopted in this article can be viewed as both theory testing and theory generating in its ambition to put an empirically untested, theoretical perspective into practice in the context of an educational activity (see Alvesson and Sköldberg, 2009).

The analysis of the empirical data involved both the researcher and the teacher (one of the two teachers who delivered the unit) who went on the trip (hereafter referred to as the ‘research teacher’). We viewed it as advantageous that one of the researchers also was a participating teacher, as it provided a contextual understanding of the students, the task at hand, and the curriculum’s intentions and impact on assessments. The participating researcher, in turn, contributed with necessary detachment from the teaching process. There are also aspects to consider when using a research-teacher approach. The arrangement might have a significant impact on the students and the teaching environment. However, since the research teacher was a part of the entire teaching process, we have assessed this as a minor risk. Another crucial aspect is the ethics; it has been essential to be transparent about the fact that the seminars also serve as a basis for research conducted by the research teacher.

The empirical data were analysed separately in several steps. During Step 1, the researcher and research teacher read both transcripts in their entirety to get an overview of the material. During Step 2, the transcripts were coded in accordance with the response dimensions, as categorised by Zachrich et al. (2020) (Table 1). Sections of the transcript that could refer to any of the categories – be they cognitive, affective or physical – were highlighted. The researcher and research teacher each conducted their own analysis, then their coding was compared, and through collective agreement grouped into categories based on the table. Altogether, 75 units were identified. Of these, it was determined that 21 units formed affective responses to the questions, then 16 units were allocated to the physical response category. Finally, 38 units were considered to comprise a cognitive response to the questions based on the theoretical model used in the analysis.

With this focus of this article being on how the students’ historical experience was linked to a particular place – in this case, the concentration camps at Auschwitz – the next step in the analysis was to read the transcripts in relation to the physical dimension and its subcategories: physiological response, sensory interaction and physical interaction. Following this, the transcripts were examined carefully for any mentions of both cognitive and affective aspects. The last stage of the analysis focused on identifying any patterns of interaction among the three categories. Special attention was paid to any indications of a connection between the physical reactions to the historical site and those associated with the other two categories, to allow for an in-depth understanding of the role that visits to historical sites play in students’ experience of history.

When interpreting the results from the theoretical analysis of the data, their limitations must be considered, including that they were based on only two recorded and transcribed examinable seminars. The analysis should be viewed as an exploratory case study, in which the empirical evidence was used to demonstrate the theoretical categories being tested. Therefore, the 75 identified units, divided across the three response categories, should not be understood as definitive proof of the validity of these generalisable categories, but rather as a representation of the response variation possible within one set of empirical data. Methodologically, the examinable seminars have been framed as focus group interviews. A content analysis has been made of the transcribed conversations that took place between the students. From this methodological point of view, the individual utterances are regarded as situational, as something that arises in the interaction in the seminar (Wilkinson, 1998). This means that the analysis focused less on statements linked to specific students, and implies that the statements may be distributed unevenly among the students. The empirical material was tested against the ready-made theoretical categories from Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model to provide greater stability to the results. This article is an initial exploratory article designed to test Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model empirically (see Berg, 2021; Schüllerqvist and Osbeck, 2009).

With that said, we would like to clarify the theoretical and methodological approach of the article. We aim to place this article within an exploratory and variation-theoretical tradition (see Pang and Marton, 2003). This leads us to be interested in qualitatively discerning different ways of experiencing visits to historical sites (Larkin et al., 2006; Runesson, 1999). In the analysis, our focus is not on the number of statements made by each student, or the quantity of statements within a category. Instead, we aim to explore whether the statements can be placed qualitatively within or in relation to the categories, which is a common approach if one analytically wants to test new questions within a field (see Bryman, 2003; Cohen et al., 2007; Denscombe, 2009). In this case, we are testing a theoretical model by comparing it to a smaller empirical data set in order to evaluate its initial explanatory power. The goal has been to find supporting or complementary statements to the tested model, not to pursue theoretically saturated categories.

Results

After reviewing the students’ accounts of their visit to Auschwitz during the examinable seminar held upon their return to Sweden, it was evident that they acquired three distinct types of experience. The first related to the varying physical experiences that students had while on the trip. The second type is related to the various students’ myriad affective and cognitive responses to the physical site. Finally, the analysis of the transcripts reveals how the students actualised several different meta-perspectives.

Statements about physical interactions and responses

Physiological response

This response entails physical reactions associated with a place-based encounter, pointing to a pre-reflexive experience – to Erlebnis. Examples of this might include shivering, having goosebumps or feeling nauseous. During the seminars observed in this study, the students often recalled having this type of experience.

Teacher:Were you able to sense that even if it felt unreal, you could tell it was a place where something had happened?

Student 3:In a way, you could sort of just breathe it in the air.

Student 4:Yes, it left me with a feeling of unease.

Student 1:Yes, you didn’t exactly walk around feeling happy.

Teacher:Is it possible to put that experience into words?

Student 4:It was almost like you were sometimes being suffocated. When you went into some of the rooms, it was a bit difficult to breathe. (Group 2)

As the quotation indicates, Students 1, 3 and 4 described their experiences together in physiological terms, as ‘feelings of panic’, of finding it ‘difficult to breathe’ or having the sensation that they were ‘being suffocated’ during the visit. However, there were only a few cases in which this type of language was used, and purely bodily pre-reflexive experiences were mentioned. One possible explanation for this may be the nature of the empirical data. During the seminars, the students were encouraged to talk about how they felt while they were at the concentration camps. Thus, they were talking about their experiences after their visit, and it seems reasonable to assume that the results might have been different had the students’ physical encounters with the place been observed at the time. The physical responses noted in the empirical material collected in this particular case tended to relate to Zachrich et al.’s (2020) sensory interaction subcategory, which is described and developed below.

Sensory interaction

Within Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model, the ‘sensory interaction’ subcategory describes a physical response that occurs in relation to a location or place. Unlike the ‘physiological reaction’ subcategory, which focuses on the reaction to a stimulus, rather than the stimulus itself, this second variant of physical response concerns the relationship between conscious sensory impressions and place.

Evidence of sensory interaction appears more frequently in the empirical data than the other two physical responses. It is easier to identify because it can be talked about, unlike a physiological reaction, which might hardly be noticed or observed. Sensory interaction is a response that seems to combine experience (Erfahrung) with the retrospectively oriented method of data collection. Generally, this points to the interplay between place and physical response. Additional examples in the empirical data are evident when the students describe what happens to them when they look at the photographs they took during their visit.

Teacher:What, if anything, was left?

Student 2:Where they were gassed. This is what strikes me when I look at the pictures.

Student 4:It’s the place itself. Just the whole thing, really. To me, it’s like, I get so emotional, or things come back to me when I tell people about it. People who haven’t been there. Then for me, things get difficult. I guess it’s the whole thing. (Group 2)

Statements that were expressed during the seminars highlight the distinction that students in this study made between their prior impressions of the place and the place itself: the physical experience of being there gave them a deeper understanding of the place.

Physical interaction

Within Zachrich et al.’s (2020) physical response category, the physical interaction subcategory encompasses movement through and around a place. This entails an experience that can be physical in terms of scale and the relationships of the place. In the empirical material generated for this study, students were active and took the initiative to discover the place they were visiting. One example is when Students 1 and 4 in Group 1 express surprise that the concentration camps were located so close to residential areas, and that people lived their lives pretty much as usual despite what was happening a mere stone’s-throw away.

Student 1:Yeah, that it was exactly the same, that gate of death – that they, you know, erected it.

Student 4:The location was also so unreal. It felt like it wasn’t real.

Teacher:What did you think about the camp’s location, about where it was situated?

Student 4:Well, it was in a residential area. Children were out playing. Then it felt like, like it was kind of not real. Because, I mean, who would want to live there? If it really had happened? (Group 1)

The importance of seeing the place with their own eyes is something that Students 1 and 4 in the example above returned to during the seminars. Some students said that once they had experienced the site, it became difficult for them to understand how anyone could question the fact that the Holocaust had taken place. It was as though the visit had made this historical event more tangible and real – as though the visit had made it true.

Teacher:When you’ve gone and looked at something, do you think it’s possible that you actually get something more than what’s there? Can you get something more?

Student 6:Yes, but I feel like … when you are there, you try to picture what happened. Do you know what I mean? Personally, I think I get more the fact that it really did happen from being there than if I just sat reading about it. I take it more seriously than when I read about it. (Group 1)

Student 6 in Group 1 stated that there was a ‘something else’ in the experience of the place, something that many of the students in the study returned to, something that gave them more than they would have got from just reading about the Holocaust in a textbook. There seems to be something powerful about visiting the site itself – it becomes an encounter with the traces of the past in which one form of experience (Erlebnis) feeds another (Erfahrung).

Throughout the empirical material considered in this study, students express that during their experiences encountering the historical site, time and space become linked. The empirical data demonstrate how students’ understanding of historical time is enhanced by visiting the historic site and how it enables them to reach a better understanding of historical time. The specific, distinguishable character of Holocaust memorial sites activates the affective and bodily dimensions of learning. It is as if the entire site exists in its original time period, and that it creates an experience of a ‘then’ to take place now; that is, at the time of the site visit. A conflict between then and now – past and present – develops to different degrees among the students in the empirical data.

Affective and cognitive responses during school trips

Affective responses to place

In addition to the physical responses that the students in different ways demonstrate in the empirical material, their statements also reflect the interplay between physical and affective responses. Here, it is possible to distinguish between the affective responses that students express concerning the visit itself and those expressed after their return home to Sweden. For example, several students have affective responses to the view and presence of the human hair on display during their visit, particularly their reflections on the sense of historical proximity.

Teacher:It makes you think: How much does the hair of one person weigh?

Student 1:Isn’t it just 100 grammes? I think they said 150 grammes. And there was, like, seven tonnes there.

Student 4:I think it was two tonnes.

Student 1:Yes, but there were seven in total, and that was nothing compared with what there really was.

Teacher:What can you learn from visiting such a room as that then? Is there anything to be learned?

Student 1:Once you get to see it, then it becomes real somehow. It can get very emotional, seeing such things. Sort of like if I had looked at a picture of hair, I would have just said, ‘How horrible’, but when I got to see it in reality – that there’s so much hair just lying there – then I was like, ‘Crap, this really happened!’ (Group 1)

In this case, the ‘very emotional’ and ‘horrible’ reaction that Student 1 in Group 1 expressed concerning the sight of real human hair led to the realisation that the Holocaust actually took place. In other examples, it is possible to identify affective responses in some of the students’ statements after they returned home. The conversation cited below seems to suggest that some students in this case used their time during the trip to document their encounters (‘It was cool to be able to see things’) and leave their affective reflections for the period after their return (‘ … that’s when I thought more about my emotions … ’).

Teacher:Do you think of other things now than you did when you were there? Do other things come to mind?

Student 2:I think that … I actually agree with her a lot. Back then, when I was there, there was a lot, and I took pictures of as many things as possible. It was cool to be able to see things. When I got home, that’s when I thought more about my emotions and things. Where we really had been. (Group 2)

Like Student 2, other students speak about their affective responses from the trip. Some talk about their emotions ‘catching up with them’, and how, since returning home, they have really started to reflect on where they have been and their feelings about the place they have visited. Many of these responses can be categorised as ‘awe and reverence’. Like Student 2, other students also express a sense that they have been to a special place, which conveyed more to them than words or texts ever could.

Cognitive responses to place

We notice two main cognitive responses in the empirical material: contextualisation and sense of insight. Some of the students in this study have used the trip to contextualise their understanding and interpretation of the sources they encountered that relate to the Holocaust. In the conversation below, the students discuss in this group how the physical and scientific evidence they saw while at Auschwitz pose a challenge for Holocaust deniers, and provide an opportunity for a more nuanced engagement with historical sources and artefacts.

Teacher:What do we think about those who deny it took place?

Student 1:I don’t understand how they can. They can’t have been there. They probably just looked at Flashback [a Swedish website] or something like that and wrote that it didn’t happen. But then I think if they were to go there, they’d change their minds. Seeing a dilapidated gas chamber, it’s like it really happened.

Student 2:I read that they said they washed clothes there using Zyklon B.

Student 4:There was someone who said – so that about sources – that they claimed there wasn’t any Zyklon B and that’s why it didn’t happen.

Student 3:They have found Zyklon B in their hair, so evidence exists. It’s the same thing as when they found loads of body parts in the ground. I mean, they’ve [Holocaust researchers] checked up on it. So, I don’t understand why they [Holocaust deniers] stick to what they’ve said about it not happening. There’s evidence. (Group 2)

This conversation between Students 1, 2, 3 and 4 in Group 2 highlights the point that, in this case, the students identify the scientific evidence of Zyklon B in Holocaust survivors as proof that the Final Solution did take place. Another student also remarks on the evidence indicating signs of Zyklon B at Auschwitz. Still, seeing the physical remains of a gas chamber was, for them, proof that ‘it really happened’. The physical site then becomes contextual proof of the historical event in the students’ interpretation. However, the effort to unite their evidentiary knowledge of the Final Solution with what they saw during the trip, combined with the privileged knowledge that the passage of time has given them, causes several students to express a sense of unease or ‘feelings of panic’.

Teacher:What kinds of feelings do you get, and where do they come from?

Student 4:It’s like you know what happened there. In that way, it’s there, in our minds. We know what happened there. Even though it is very difficult to take in, we still know.

Student 1:Yes, if you got feelings of panic, you know, we were actually allowed to and could leave. But they [the victims] didn’t get to. When we went in there [the gas chamber], we knew they [the victims] could never leave. It was feelings of panic, but you couldn’t really take it in. (Group 2)

Among the obvious affective responses articulated here, Student 4 also expresses the cognitive understanding that the Holocaust actually took place. The student points out the difficulty of comprehending the historical event as a reality, but states how this was somewhat resolved by their visit to the concentration camp. Student 1 articulates a similar bafflement that arose among them from the insight that, unlike the people at the time, they knew what was coming and could leave.

When the students in this study recount their affective and cognitive experiences during the study trip, to different extents, they express this relationship through various combinations of time and place. The physical interaction with the place seems to trigger affective responses upon the return home; for example, when the students are asked to describe their experiences during the trip, for some of them, it is the memory of their feelings from being at the site that comes to mind. In this case, the students are returning to the historic site in their minds and thinking about what they experienced. This process allows them to connect the present, their encounters with remnants of the past and their intellectual understanding of what historically occurred at a physical site. In terms of cognitive response, the historical site seems to activate the students’ existing contextual knowledge, so that they can explain to themselves what they had been experiencing during the visit. There are also indications that the physical site confirms historical knowledge that the students previously had struggled with, and that the physical interaction with the place provides them with new insights.

Physical interaction and the meta-perspective after school trips

Students’ post-visit learning

It is impossible to place all the identifiable units taken from the students’ statements and categorise them according to Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model, and we identify two meta-perspectives. One is evidenced in students’ statements when reflecting on what they learned from the school trip, in which they emphasise that they learned more from visiting the Auschwitz memorial site than they would have if they had only read about it in a textbook.

Teacher:Do we have anything else to add – any final words? If you had to summarise the experience and the school trip?

Student 4:I guess that’s also what makes it feel more like that. If we had just been here at school and read about it, it would just have been like a school subject. But now that we have been there, it becomes more …

Student 5:More personal.

Student 4:Yes, exactly. (Group 1)

However, the reflections from Students 4 and 5 are not limited to the quantity of knowledge they have amassed. They also mean that they learned things above and beyond what is customary in a school subject. As part of the same conversation, Students 1 and 4 describe how learning for them becomes more serious when visiting a historical site, that is, you must experience it yourself first hand (Erlebnis), then it becomes more personal:

Student 4:You cannot really develop a full understanding of the unloading ramp just by reading about it. You don’t really know what you’re talking about. But if you’ve actually been there, then it becomes more personal.

Student 1:You have to think a little more, like I said before. When you read about it, then it’s more like a story or a movie. But now you know exactly what it looked like, what it was like. (Group 2)

For Students 1 and 4, the place visit confirms that what is said to have happened there really did happen. Simultaneously, some of the students express a sense of ambivalence about the visit – that they both understand what happened there, but simultaneously do not. It is as if the encounter with a place, at least for these students, provides the insight that some things in history are not possible to comprehend fully.

Teacher:Do you mean the trip itself or the fact you encountered something different?

Student 3:It turned out to be very strange. You can’t really put your thoughts into words, I would say. Because it was very difficult for me ... this is, well, a place where lots of horrible things happened, and when you read about it, it’s like this thing that happened. It’s very different when you actually visit the place. So, when I think back, it was a really fun and interesting trip, and you got to learn a lot, but you still do not really understand during the visit what happened there. (Group 2)

According to Student 3, it was difficult to understand what had happened there despite the visit: ‘You can’t really put your thoughts into words, I would say.’ Thus, for the students in this study who expressed responses similar to those of Student 3, the interaction with the historical site contributes to an epistemological reflection about what it is possible to know, and perhaps even what is comprehensible.

Students’ ‘agency’ post-school trip

The second meta-perspective that we identify in the empirical material collected for this study is that in their statements, students express a willingness to act on the knowledge and understanding gained from the school trip. In these cases, the students express a desire to share their experiences. When asked how they looked back on the trip, the students in Group 1 go even further.

Student 1:I think it feels good. I think everyone who’s young should go there.

Student 2:Yes, at least those who are studying history.

Student 3:It’s quite different if you just learn about it [in the classroom]. And then, when you visit it, it’s kind of a shock when you realise it really happened. You know that something very significant happened. To share what you know so that such a thing doesn’t happen again. (Group 1)

Student 3 makes a connection between learning and activism, and the students together formulate a desire to influence their broader social context, ‘so that such a thing doesn’t happen again’. Students, such as Student 3, also express their conviction that after visiting Auschwitz, their goal is to get others to act as well.

Teacher:Why is it that important?

Student 4:It’s like we said earlier – it’s different there. It’s one thing to read about it and another to actually be there.

Student 1:It becomes more real when you see it.

Student 3:Yes, sort of live. Instead of just reading about it. That’s not as interesting. It’s a bit more exciting when you know you’re going there. You’ll soon, well, you know, really get to know what happened. And if I’m not sure whether or not it happened, well, then the picture becomes clearer when you get to see it in reality.

Student 3:Then maybe also to get other people to … to prevent it … to want to join the UN. To prevent future wars from breaking out in other countries so that people’s thoughts and views are completely changed. (Group 2)

Student 3’s experience of having been to a historical site prompts the desire not only to share the experience, but also to influence others. In this case, he wants ‘to join the UN’ and prevent future wars in other countries. In this example, the school trip becomes the experience from which Student 3 intends to try to change others’ views.

Conversations like this suggest that the students in this study can make connections between what happened in the past and what needs to be done in the future. Statements like these suggest that the students in this study are beginning to adopt a more comprehensive social perspective and thinking about change taking place over a longer period. Ideas such as joining the United Nations, with its global influence and reputation as a mechanism for preventing genocide and other human tragedies, is a good example of this. Such expressions suggest that this student’s experiences during a school study trip stimulate an enhanced time perspective. The encounter with a physical place sparks their willingness to act in the present. In this way, as the evidence of this small-scale empirical study suggests, visits to historical sites can stimulate students’ awareness of everyday life issues. The knowledge they gained from the trip has contributed to their qualitatively different view, not only of the past, but also of the future.

Conclusions and discussion

This article has analysed how the different forms of experience (cognitive, affective and physical) gained from visiting historical sites – in this case, a Holocaust site in southern Poland – can interact when examining the interpretation and historical orientation processes that upper-secondary school students express. Two research questions have been at the forefront of our analysis: (1) What forms of experience do students express, and how do these forms relate to each other?; and (2) What implications might these expressed experiences pose for how teachers organise their teaching, including trips to Holocaust memorial sites?

First, we should say something about the number of student statements that contributed to the results presented in this article. We need to bear in mind that the results are based on a total of 10 students’ contributions in two examinable seminars, divided into 75 relevant units. It should also be noted that the analysis does not so much focus on the statements of the individual students, but on how these are expressed in an interaction between students (Wilkinson, 1998). The findings aim to showcase the variation existing in the empirical data at the group level. This has resulted in an uneven distribution of students’ statements at the individual level in the presentation. The objective of this qualitative study is not to generalise, but rather to identify variations within the empirical data. The established categories should therefore not be perceived as ‘saturated’ (Berg and Persson, 2023). The students’ utterances are empirical examples of a limited display of possible ways to address questions about place and experience. The categories resulting from the empirical analysis were determined using Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model, which has been tested empirically. The aim has been to test the categories formulated theoretically against variations in the empirical material that has been analysed, in order to assess their explanatory value in relation to the research questions. We should bear in mind that, to our knowledge, this is the first empirical study exploring these questions based on the model, and that one of its goals will be achieved if future studies test the saturation in the identified empirical data (see Berg, 2021; Schüllerqvist and Osbeck, 2009).

That being said, we want to highlight some of the conclusions that can be drawn from our analysis of the transcribed examinable seminars. One is that in their comments in this empirical material, students tend to weave together the different categories and subcategories of possible responses identified in Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model. When students in this empirical material seek to put their experiences during a Holocaust site visit into words, they to some extent combine physical responses with affective and cognitive responses, often sequentially. Furthermore, it is possible to distinguish between responses in which the encounter with the physical place gives rise to distinctly affective or cognitive responses. In particular, we want to emphasise how students in the empirical data link time and place in their responses; for example, the students’ physical interaction with the site during their trip gives rise to their affective responses after returning home, almost as if they are reliving it. As demonstrated in the results, there are also examples in this study where students link their interaction with historical artefacts at the site with cognitive reasoning in the present, including reflections on their place in a historical context. In this respect, the empirical analysis of the students’ responses in this study contradicts previous research findings that suggest that affective experiences prevent effective learning (Flennegård and Mattsson, 2021).

Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model has many merits. It points out that encounters with the past can lead to different responses. From a history education perspective, the model can also be viewed as a way of mapping students’ potential to engage with history in different ways, and to formulate varying responses. We believe that our study, with due respect to the methodological limitations discussed above, strengthens this epistemological position. Simultaneously, we have discovered expressions in the students’ statements collected here that, although they are not part of Zachrich et al.’s (2020) model, we believe bolster its educational relevance.

First, there are examples in this study where the students demonstrate an epistemological awareness during the seminars, expressing how their trip provided them with unique learning opportunities that traditional teaching methods could not. However, there are examples where students also acknowledge that there may be limitations in the ability to understand the past fully. This meta-perspective on learning demonstrates an awareness among students in this study that their experiences during the school trip encourage them to help improve society by acting themselves, as well as by convincing others to act. In this way, the students express, in these cases, a historical orientation that is morally coloured and future-oriented (Rüsen, 2008). This response is in line with previous research on the educational dimensions of school trips to Holocaust sites, establishing that such visits involve not only learning about the Holocaust, but also from the Holocaust (Cowan and Maitles, 2011).

Taking into account the exploratory nature of the study, the results from our analysis of these students’ responses to a Holocaust site visit have the potential to contribute to history teaching in more than one respect. However, we have to highlight the importance of context. The examinable seminars conducted with the students after the trip tended to focus on cognitive issues, which reflects the official curriculum documents. Of the 75 meaning units identified in this study, 38 had a cognitive focus. Although it may seem that a correlation exists between the outcome and orientation of the official documents, it would not be appropriate to assume so. Another factor that probably has an impact on the results is the contemporary debate around the Holocaust. Several of the students refer to the existence of Holocaust deniers, whose actions were hotly debated at the time of the study trip. That being said, first, there are examples where, in order to comprehend their experiences, the students connect their cognitive and affective responses to their physical interactions with the place. This is a result that points to the possibilities that exist in thinking about the place in connection with the planning of teaching, and the importance of the place, and the effect that this can have on students’ learning of history. Second, there are also examples where the students make statements linking to contemporary historical–cultural debates. As suggested above, there are results indicating that students’ historical orientation, the visit, their knowledge of the historical period and their present-day experiences are bound together. Therefore, it appears that school trips can actualise the educational potential between historical–cultural contexts and contemporary social issues.

When examining the statements that a small group of Swedish students made after a physical encounter with a historical site, and when considering the context in which these statements were made, we believe that it can be argued that school trips to historical sites have the potential to help develop history education. Notably, the preparation and follow-up work for a study trip can significantly impact the overall outcome. That being said, and with respect to the explorative and limited empirical scope of this study, we also believe that these results can serve as a reference point for teachers’ understanding of the potential of study trips, while laying the foundation for further studies of this practice. We have identified patterns in the examined data suggesting that experiencing the past at a historical site creates new opportunities for students’ learning, while bolstering their capacity for historical meaning making. Visits to historical sites provide the context not only for cognitive experiences with the past (Erfahrung), but also for affective and physical experiences (Erlebnis).

By incorporating visits to historical sites into curricula, history education can provide an opportunity for students to think critically about the past and perceive its relevance in their daily lives, as well as to understand that they are shaped by history and take part in shaping it simultaneously.

Open data and materials availability statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations and Conflict of Interests

Research ethics statement

The authors conducted the research reported in this article in accordance with the research ethics standards of Dalarna University.

Consent for publication statement

The authors declare that research participants’ informed consent to publication of findings – including photos, videos and any personal or identifiable information – was secured prior to publication.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with this work. All efforts to sufficiently anonymise the authors during peer review of this article have been made. The authors declare no further conflicts with this article.

References

Alvesson, M; Sköldberg, K. (2009). Reflexive Methodology. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage.

Arthos, J. (2000). ‘”To be alive when something happens”: Retrieving Dilthey’s Erlebnis’. Janus Head 3 (1) : 77. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5840/jh2000316

Bartelds, H; Savenije, GM; Van Boxtel, C. (2020). ‘Students and teachers’ beliefs about historical empathy in secondary history education’. Theory & Research in Social Education 48 (4) : 529. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2020.1808131

Berg, M. (2021). ‘Combining time and space: An organising concept for narratives in history teaching’. Acta Didactica Norden 15 (1) : 1. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5617/adno.7860

Berg, M; Persson, A. (2023). ‘The didactic function of narratives: Teacher discussions on the use of challenging, engaging, unifying and complementing narratives in the history classroom’. Historical Encounters 10 (1) : 44. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.52289/hej10.104

Brooks, S. (2008). ‘Displaying historical empathy: What impact can a writing assignment have?’. Social Studies Research and Practice 3 (2) : 130. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/SSRP-02-2008-B0008

Bryman, A. (2003). Samhällsvetenskapliga metoder. Malmö: Liber Ekonomi.

Carr, D. (2014). Experience and History: Phenomenological perspectives on the historical world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, L; Manion, L; Morrisson, K. (2007). Research Methods in Education. London: Routledge.

Cowan, P; Maitles, H. (2011). ‘Teaching the Holocaust: To simulate or not?’. Race Equality Teaching 29 (3) : 46. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18546/RET.29.2.12

Davis, OL, Yeager, EA; EA and Foster, SJ SJ (eds.), . (2001). Historical Empathy and Perspective Taking in the Social Studies. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Denscombe, M. (2009). Forskningshandboken – för småskaliga forskningsprojekt inom samhällsvetenskaperna. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

Endacott, J; Brooks, S. (2013). ‘An updated theoretical and practical model for promoting historical empathy’. Social Studies Research and Practice 8 (1) : 41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/SSRP-01-2013-B0003

Endacott, JL; Brooks, S. (2018). ‘Historical empathy: Perspectives and responding to the past’. The Wiley International Handbook of History Teaching and Learning. McArthur Harris, L, Harris, LM LM (eds.), Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 203.

Flennegård, O. (2018). Besöksmål Auschwitz: Om svenska resor för elever till Förintelsens minnesplatser. [Places to visit Auschwitz: School trips to Holocaust memorial sites]. Stockholm: Forum för levande historia.

Flennegård, O; Mattsson, C. (2021). ‘Teaching at Holocaust memorial sites: Swedish teachers’ understanding of the educational values of visiting Holocaust memorial sites’. Power and Education 13 (1) : 43. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1757743821989380

FRA (European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights). (2011). Discover the Past for the Future : The role of historical sites and museums in Holocaust education and human rights education in the EU: summary report. Vienna: European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2811/29240

Gadamer, H; Weinsheimer, J; Marshall, DG. (2004). Truth and Method. 2nd ed. London: Continuum.

Larkin, M; Watts, S; Clifton, E. (2006). ‘Giving voice and making sense in interpretative phenomenological analysis’. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2) : 102. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp062oa

Lee, P; Shemilt, D. (2003). ‘A scaffold, not a cage: Progression and progression models in history’. Teaching History 113 : 13.

Levstik, LS; Gwynn Henderson, A; Lee, Y. (2014). ‘The beauty of other lives: Material culture as evidence of human ingenuity and agency’. The Social Studies 105 (4) : 184. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00377996.2014.886987

Ludvigsson, D; Stolare, M; Trenter, C. (2021). ‘Primary school pupils learning through haptics at historical sites’. Education 3–13 50 (5) : 1. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2021.1899260

Marcus, AS. (2007). ‘Representing the past and reflecting the present: Museums, memorials and the secondary history classroom. The Social Studies 98 (3) : 105. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/TSSS.98.3.105-110

Marcus, AS; Levine, TH. (2011). ‘Knight at the museum: Learning history with museums’. The Social Studies 102 (3) : 104. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00377996.2010.509374

McKernan, A. (2018). ‘Affective practices and the prison visit: Learning at Port Arthur and the Cascades Female Factory’. History of Education Review 47 (2) : 131. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/HER-11-2017-0023

Nesfield, V. (2015). ‘Keeping Holocaust education relevant in a changing landscape: Seventy years on’. Research in Education 94 (1) : 44. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7227/RIE.0020

Pang, MF; Marton, F. (2003). Beyond “lesson study”: Comparing two ways of facilitating the grasp of some economic concepts. Instructional Science 31 (3) : 175. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1023280619632

Persson, A; Berg, M. (2022). ‘More than a matter of qualification: Teachers’ thoughts on the purpose of social studies and history teaching in vocational preparation programmes in Swedish upper-secondary school’. Citizenship, Social and Economics Education 21 (1) : 61. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/20471734211067269

Rantatalo, P. (2002). ‘Den resande eleven: Folkskolans skolreserörelse 1890–1940’ [The travelling pupil: The school journey movement in Sweden]. PhD thesis. Umeå, Sweden: Umeå University.

Richardson, A. (2021). ‘Site-seeing: Reflections on visiting the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum with teenagers’. Holocaust Studies 27 (1) : 77. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2019.1625121

Rohlf, G. (2015). ‘How to make field trips fun, educational and memorable: Balancing self-directed inquiry with structured learning’. The History Teacher 48 (3) : 517.

Runesson, U. (1999). Variationens pedagogik: Skilda sätt att behandla ett matematiskt innehåll. Gothenburg Studies in Educational Sciences 129. Gothenburg: ACTA Universitatis Gothoburgensis.

Rüsen, J. (2008). ‘Narrative competence: The ontogeny of historical and moral consciousness’. History: Narration, interpretation, orientation. 1st ed. Rüsen, J (ed.), New York: Berghahn Books, pp. 21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt1x76fc2.7

Savenije, GM; de Bruijn, P. (2017). ‘Historical empathy in a museum: Uniting contextualisation and emotional engagement’. International Journal of Heritage Studies 23 (9) : 832. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1339108

Savenije, GM; Van Boxtel, C; Grever, M. (2014). ‘Learning about sensitive history: “Heritage” of slavery as a resource’. Theory & Research in Social Education 42 (4) : 516. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00933104.2014.966877

Schüllerqvist, B; Osbeck, C. (2009). Ämnesdidaktiska insikter och strategier – berättelser från gymnasielärare i samhällskunskap, geografi, historia och religionskunskap. [Subject-specific didactic insights and strategies – stories from upper secondary school teachers in social studies, geography, history and religious education]. Karlstad: Karlstad University Press.

Seixas, P. (2017). ‘A model of historical thinking’. Educational Philosophy and Theory 49 (6) : 593. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1101363

Skolverket Lgy. (2011). Ämnesplan Historia. [Swedish National Agency for Education, Curricula Upper-secondary School 2011, Syllabus in History]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

Smith, L. (2021). Emotional Heritage: Visitor engagement at museums and heritage sites. London: Routledge.

Spalding, N. (2011). ‘Learning to remember slavery: School field trips and the representation of difficult histories in English museums’. Journal of Educational Media Memory and Society 3 (2) : 155. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3167/jemms.2011.030209

Stolare, M; Ludvigsson, D; Trenter, C. (2021). ‘The educational power of heritage sites’. History Education Research Journal 18 (2) : 264. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14324/HERJ.18.2.08

Tapper, B. (1925). ‘Dilthey’s methodology of the Geisteswissenschaften’. Philosophical Review 34 (4) : 333. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2179376

Trofanenko, BM. (2011). ‘On difficult history displayed: The pedagogical challenges of interminable learning’. Museum Management and Curatorship 26 (5) : 481. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2011.621733

Trofanenko, B. (2014). ‘Affective emotions: The pedagogical challenges of knowing war’. Review of Education, Pedagogy and Cultural Studies 36 (1) : 22. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10714413.2014.866820

VanSledright, B. (2011). The Challenge of Rethinking History Education: On practices, theories and policy. London: Routledge.

Wetherell, M. (2012). Affect and Emotion: A new social science understanding. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage.

Wilkinson, S. (1998). ‘Focus group methodology: A review’. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 3 (1) : 181. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13645579.1998.10846874

Witcomb, A. (2013). ‘Understanding the role of affect in producing a pedagogy for history museums’. Museum Management and Curatorship 28 (3) : 255. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2013.807998

Zachrich, L; Weller, A; Baron, C; Bertram, C. (2020). ‘Historical experiences: A framework for encountering complex historical sources’. History Education Research Journal 17 (2) : 243. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14324/HERJ.17.2.08

Zerubavel, E. (2003). Time Maps: Collective memory and the social shape of the past. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.