Introduction

Radicalisation among young people and the associated risk of violence have become a growing problem in many countries around the world. In recent decades, there has been a remarkable increase in hate speech and attacks on migrants and refugees, alongside an increase in religious and political extremism and terrorist attacks. These incidents and concerns have highlighted the need for professional work with young people to identify and address the causes of extremism, prevent radicalisation and marginalisation, strengthen youth resilience and promote equality. We perceive radicalisation as individual thought patterns and notions of feeling like a stranger in a hostile environment. These notions are nurtured and develop in communities and networks with other young people who share similar experiences of exclusion. While there is no doubt that the cognitive readiness of radicalised youth is an important prerequisite for violent terrorism, this does not mean that all radicalised young people are potential terrorists. We therefore focus exclusively on preventing radicalisation, and not on preventing terrorism or dealing with those who are already radicalised.

Prevention of social problems among children, young people and adults is the primary task of social pedagogy. The integration of marginalised groups into society is the main goal of Danish social pedagogical practice and it defines the identity of the profession. Historically, the field of social pedagogy has dealt with marginalised children, young people and adults, which nowadays also includes the minority youth at risk of radicalisation.

The social pedagogical objective of preventing social problems is also reflected in Danish legislation. This is stated in the Act on day care services, leisure and club services (Dagtilbudsloven), which regulates pedagogic work with children and young people. The legislation sets out four types of tasks that pedagogues in youth clubs should work with:

-

a development task, where the youth club must support young people’s all-round development and ability to join communities

-

a pedagogical task, where young people must be brought up to uphold democracy

-

an information task, where young people must be informed about other leisure opportunities in the local community

-

a support function, where young people’s attachment to the education system and to the labour market must be supported.

In the implementation of this legal directive, social pedagogical practice naturally takes many different forms. In the intersection of young people at risk of radicalisation and marginalised residential areas where those young people often live, social pedagogical practice takes a disciplinary form (Tireli, 2016). The social pedagogical focus here is often on the individual young person – on their family and cultural background, as well as the lack of will and motivation for social mobility as explanations for the young person’s tendencies towards radicalisation. Behaviour correction and training towards an idealised average youth identity then becomes the typical area of focus. The success criteria for social pedagogy are often defined in relation to the ability to prevent and eliminate ‘abnormal’ and ‘undemocratic’ forms of behaviour (Tireli, 2016; authors’ own translation).

Social pedagogical work with young people at risk of radicalisation often overlooks the structural and political conditions that largely underlie the (re)production of tendencies towards radicalisation (Danbolt and Myong, 2018). This leaves the mechanisms of exclusion intact; consequently, different logics, discourses, mainstream perceptions and hidden rules embedded in these mechanisms of exclusion create certain forms of power and powerlessness and exclusion for ethnic minority youth.

When the broad mechanisms of exclusion are perpetuated, the relationship between the young person at risk of radicalisation and the social pedagogue becomes difficult, because social pedagogy appears as an effort to preserve those mechanisms. This can provoke radicalisation tendencies among young people. A trusting relationship between the young person and the social pedagogue is a prerequisite for meaningful social work. There is therefore a need for social pedagogical practice that responds to structural conditions that threaten to radicalise young people.

In order to draw social pedagogical attention to the structural conditions at play, we first delineate a brief picture of the political discourse in Denmark – a discourse where radicalisation is a floating signifier. We identify and describe the system and structure that continually constructs ethnic minority youth at risk of radicalisation. We do this by pinning down the dominant discourse about ‘foreigners’ and analysing some administrative measures (such as the intensified punishment zone) as backdrops for a structural understanding of youth and social pedagogical practice.

Political discourse on ‘foreigners’ and radicalisation

As previously stated, this article does not deal with already-radicalised youth or with extremist social environments. It focuses, rather, on ethnic minority youth who are at risk of radicalisation. These young people face various risk factors, such as being immigrants and having immigrant descendants, being confined to marginalised residential areas, suffering from poor schooling or lack of education, experiencing stigmatisation and abuse in public spaces, and scarcity of resources, among others (BL, 2023). These factors can lead young people to close themselves off from society, live according to religious precepts or in extreme cases commit assaults on what or who they believe represents the opposite of what they stand for (Mørch, 2012).

There is a social pedagogical concern (Brønsted, 2021) for this group of young people who do not display the kind of behaviour that is considered to be common and mainstream. The ‘inappropriate’ behaviour is attributed to different reasons, but a prevailing view seems to be blaming the victim, as young people’s socio-cultural and religious backgrounds, as well as personal and family relationships, are perceived to be the primary cause of their radicalisation tendencies. These factors are also regarded as areas for social pedagogical interventions. Issues and causes that lie outside the individual are, it seems, free from political and pedagogical criticism and intervention.

Political discourse that encourages radicalisation tendencies

For effective practice, it is essential that social pedagogues link the structural conditions and the individual profiles to a greater extent. This means, among other things, paying attention to the political discourse that creates stigmatisation and exclusion of young people with ethnic minority backgrounds. We therefore briefly describe the political discourse to clarify what such progressive social pedagogy must be aware of.

Immigrants and descendants of immigrants have been increasingly establishing themselves in Denmark (Arendt, Dustmann and Ku, 2022; Jakobsen, 2000). More and more people are pursuing an education, getting a job or starting their own business, just as more and more people are obtaining Danish citizenship and buying their own house and car. Parallel to this positive development, however, people from minority ethnic communities are still overrepresented among criminals, the unemployed and the poor. For years, various groups of people have tried to understand and explain this overrepresentation; the concept of integration has been the focal point here and it is related to the theme of radicalisation in the public debate. The assumption here is that more integration means less radicalisation.

It was after the 1980s that Denmark began to articulate the concept of integration and view immigrants (‘foreigners’) as permanent residents. The focal point of the debate was primarily the public expenditure that increased due to immigration, but there were also voices from the right-wing populist party – the Fremskridtspartiet – who pointed to problems associated with Muslim migrant workers. The Fremskridtspartiet also highlighted the threat that migrants pose to Danish values (Jensen, Weibel and Vitus, 2017; Østergaard, 2007).

The public and political debate took a significant turn in the 1990s. It was a period of great social upheaval where the outsourcing of jobs intensified mobility and global migration influenced the debate, which became centred on the ‘problems’ associated with immigration from countries where the culture is fundamentally different from that of Denmark. Cultural differences in everything from clothing, food and marriage, to settlement in ‘ghettos’ and the will to integrate were increasingly seen as a barrier to integration, and the ‘foreign’ cultures being perceived as a threat to Danish values and to social cohesion, which was put forward as something particularly Danish (Østergaard, 2007). Parallel to this development, some European countries suffered several terrorist attacks carried out by self-proclaimed Islamist groups or individuals throughout the 2000s and 2010s. This contributed to directing the debate on integration towards Muslim populations.

Since 2001, the public and political debate has become increasingly centred on values – which were first referred to as basic democratic values but quickly became Danish values, even though these values only referred to universal concepts such as equality, democracy and freedom of expression (Olwig and Pærregaard, 2011). In particular, freedom of expression became a focal point in 2005,1 when the Danish government was adamant that freedom of expression was a uniquely Danish democratic value.

Gradually, a discourse emerged, which has become so dominant that it has functioned as legitimisation of political interventions against phenomena and groups in society perceived as threats to social cohesion (Jensen et al., 2017; Olwig and Pærregaard, 2011). It is argued that since the 9/11 attacks in the United States, the public space has been dominated by a discourse about Islam that links the religion to terrorism and radicalisation. Since the terrorist attack in Copenhagen in the winter of 2015, in which a 22-year-old perpetrator shot and killed two innocent people, the media have talked about the darkened ideology of Islam. The tone of the debate became markedly harsher, and it helped to maintain an ‘us and them’ dichotomy, as the terms Muslim(s) and Islam were linked to terrorism. Many proposals have been put forward for what should be done, including suggestions that politicians should limit immigration, especially from certain countries. It is also claimed that ‘The terror that exists stems from Islam’, and that ‘every politician should familiarize themselves with the greatest danger we face today, namely Nazi Islamism’ (Khader, 2015, n.p.; authors’ own translation). In short, this discourse claims that ‘the problem is that Islam is not only a religion, but a totalitarian ideology that permeates all aspects of everyday life, and that jihad is inseparable from Islam’ (Johansen, 2015, n.p.; authors’ own translation).

‘Ghetto packages’: an example of the realisation of the political discourse

The discursive development was followed by political actions in the form of ‘ghetto packages’, and in 2010 the Danish government adopted an action plan, which emphasised that:

These are strong values that hold Denmark together and that we must not compromise. But today there are places in Denmark where Danish values are no longer sustainable. And where the rules that apply in the rest of society therefore do not have the same effect. Such conditions prevail today in parts of the residential areas that we colloquially call ghettos.

In the same year, the government presented the first ‘ghetto list’ – a list of residential areas that aligned with a number of criteria on employment, education, crime and ethnicity.2 In 2020, the government coined the term ‘hard ghetto areas’, which are residential areas that have been a ghetto area for at least four years (Bolig og Planstyrelsen, 2020). The Parallel Society Agreement describes how to deal with the hard ghetto areas.

The target group of the Parallel Society Agreement is refugees and immigrants. It is held here that this group of residents is an economic burden to the welfare state and a threat to Danish culture. A report from the Ministry of Finance points out that ‘immigrants and descendants from certain countries cost Denmark DKK 36 billion in 2015’ (Parallelsamfundsaftalen, 2018, p. 5; authors’ own translation). The Parallel Society Agreement draws on the same elements and basic understandings that have been structured in the political discourse over recent decades. The basic argument is based on a claim that this group of citizens refuses to integrate, lives its life isolated from Danish society and maintains its ‘backward culture’ with ‘associated oppression’ and ;social control’ (Tireli, 2022).

The ‘parallel society’ is seen as more than living in a residential area with other groups of ethnic minorities. It is also about a lack of connections to the labour market and education, and opting out of interaction with Danes, which is seen as a conscious choice and not as a result of the conditions in the labour market and other structural conditions.

Political solutions

The Parallel Society Agreement also has ‘solutions’ to the above-mentioned problems. These solutions generally consist of several requirements, prohibitions, expectations, sanctions, punishments and incentives for ethnic minority residents. For example, the housing associations must reject those who are looking for an apartment if they are receiving social benefits. As a solution to the problems of insecurity, crime and vandalism, the term ‘penalty zone’ was introduced. It is a supplement to the previously introduced ‘visitation zone’, stating that offenders are punished more severely (up to twice as severely) if the offence is committed in an area defined as a penalty zone. The Parallel Society Agreement also suggests the preservation of an earlier rule that criminals must be prohibited from settling in a marginalised residential area. At the same time, it is already possible to evict an entire household from an apartment if only one member of the household has committed a crime in or around a marginalised residential area (Parallelsamfundsaftalen, 2018, p. 23). Furthermore, financial sanctions were introduced for parents of young children, for instance if they do not send their children to day care from the age of one.

It is therefore clear that the political discourse and the subsequent implementations are exclusionary and discriminate against a certain population group, and to that extent cause young people from ethnic minorities to act in ways that are perceived as wrong, inappropriate and undemocratic. Social pedagogical practice will therefore have difficulty achieving success with its radicalisation prevention work if it does not also contend with these discriminatory initiatives.

Prevention of radicalisation

Since 2014, prevention of radicalisation and extremism in Denmark has been conducted across authorities and in close cooperation between several ministries, probation services and the Danish Security and Intelligence Agency, as well as local authority actors in municipalities and police districts (Regeringen, 2014). Various projects have been launched, based on a so-called prevention pyramid with three interdependent layers: a basic preventive level; an intermediate anticipatory level; and an overlying interventional level. The impact of this work has been criticised for having limited scope – the essence of the criticism is that initiatives are not directed at the radicalisation process, but at the young people who have broken terror legislation (Dahlgaard, 2017). The goal here is to keep the young person in civil society and prevent radicalisation that stems from that person feeling excluded from the dominant society.

Prevention in Europe

A limited number of European projects can serve as inspiration for social pedagogical projects that are based on real prevention and not merely on preventing monocausal connections between radicalisation and terrorism. It has been difficult to trace projects in the Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN, 2017) database3 that are based on cooperation between authorities and local networks, and which are close to the young people at risk of radicalisation by building on their own experiences and needs, or projects that include structural inequality as an explanation and action parameter.

To some extent, existing projects are based on the fight against terrorism, which is predicated on two main pillars: exit programmes4 and mentoring. These two paths can form appropriate initiatives that can also be used in social pedagogical prevention work. But overall, the initiatives are aimed at young people who are already radicalised to such an extent that they have deliberately chosen an illegitimate way of life. In those projects, it appears that the discourse of the authorities plays a significant negative role: the management team, social educators and young people in RAN seem to be unsure of the use of the conceptual apparatus created by the authorities about radicalisation. The authorities’ prevention models are substantially cognitive and rationalistic: the assumption is that with information, patience and especially repetitions of the same message, young people at risk of radicalisation will be led towards sensible actions; through training and work, they will be steered towards self-sufficiency, starting a family and behaving in a way that is deemed in the eyes of the majority as neither conspicuous nor isolationist.

Reflections on social pedagogical prevention and some conclusions

Professional practices with individual solutions to complex social and political problems entail a risk of contributing to depoliticisation and undermining professional credibility. The fact that several authorities have to work together not only makes prevention work more complex, but also overlooks the necessary political dimension of prevention work. Social pedagogical work often acts blindly in relation to the political context; it has been individualised since the 1980s, which has made it difficult to challenge the exclusionary policies in the field (Guru, 2012; Herz, 2016). Although social pedagogues and other social workers have often stated goals such as non-discrimination and human rights, it has been difficult to put these ambitions into practice. Research has shown this in relation to people of colour in the United States, who have long been controlled rather than helped by social pedagogues and other social workers (Dominelli, 2008; Guru, 2012).

Prevention work has therefore been perceived by young people as irrelevant, as social surveillance and as attempts to acclimatise them to ways of life synonymous with a hostile majority society. Social pedagogical projects are adapted to municipal agendas with entirely different objectives and are not aimed specifically at preventing radicalisation. Larsson and Björk (2015) believe that political and social factors are often included as part of the problem description, but they rarely appear in the practical initiatives that are proposed or implemented. This is also evident in the RAN projects: unemployment, poverty, racism and social marginalisation are overlooked as causes of radicalisation, and the preventive measures are rarely aimed at changing these conditions. Theories about social pedagogical prevention programmes for young people at risk of radicalisation are almost entirely absent. This is problematic, in light of the fact that much social pedagogical prevention work has affected the actors and their surroundings, but without the effects of those efforts being documented (Herz, 2016).

Social pedagogues face many challenges in dealing with radicalisation, and those challenges depend on the specific context. Prevention must therefore be adapted to the particular types of factors that influence the ‘local’ radicalisation processes. This makes it more difficult for social pedagogues to work purposefully to devise strategies and approaches for prevention efforts, and to define their role in contexts where only a few general guidelines and many ad hoc decisions apply. There is a need to better understand the many causes that lead to radicalisation and the reasons that young people become involved in extremist groups. Finally, there is a need for social pedagogues to recognise the first signs of radicalisation and know how to deal with young people who are at risk.

With the background of the RAN projects and based on experiences with social pedagogical inclusion projects in Denmark, we can set out the following guidelines for structurally changing prevention work in the future:

-

Partnerships must be built with other social actors so that values from those domains can penetrate the anti-radicalisation work

-

Young people at risk of radicalisation must develop their critical skills so that they have more opportunities and better future perspectives in their personal and work lives

-

Young people must experience alternative role models and must have the opportunity to discuss messages that encourage violence and racism. This must be done by developing young people’s critical thinking and by being open to those young people’s criticism of the norms of the dominant society.

Some of the ways of working with young people to overcome these challenges include positive development of their identity through education and practical training, as well as involving relevant social networks – parents, families, peers and local communities – and in a wider sense the promotion of social cohesion, stability, positive and socially inclusive environments, and offering learning and development opportunities. In the following section, we outline a model for prevention based on these principles.

Outline for a community-oriented approach

Jasko, LaFree and Kruglanski (2017) propose a social psychological significance theory, which, we believe, in contrast to the general theories of youth and socialisation, can explain how a radicalisation process takes place. This theory points out three general driving forces: need; narratives; and social networks. First, the theory explains that people have a need for someone or something that can give meaning to their own life. Second, it emphasises that narratives – that often glorify violence – push the young person towards a radicalisation process, where the person gains a meaning that they are denied by the dominant society. Finally, there is usually a network of people who subscribe to the same narratives and which, by virtue of the strength of the collective, causes the individual to perceive the narratives justifying violence as cognitively accessible and morally accepted.

Some types of social networks end up legitimising violence, demonstrating that the presence of radicalised others in the individual’s immediate environment increases their likelihood of using violence. However, conversely, and based on the same theory, Jasko et al. (2017) hypothesise that it is likely that non-violent social connections can serve as a protective factor that prevents a person from engaging in extreme violent behaviour.

A concrete social pedagogical model

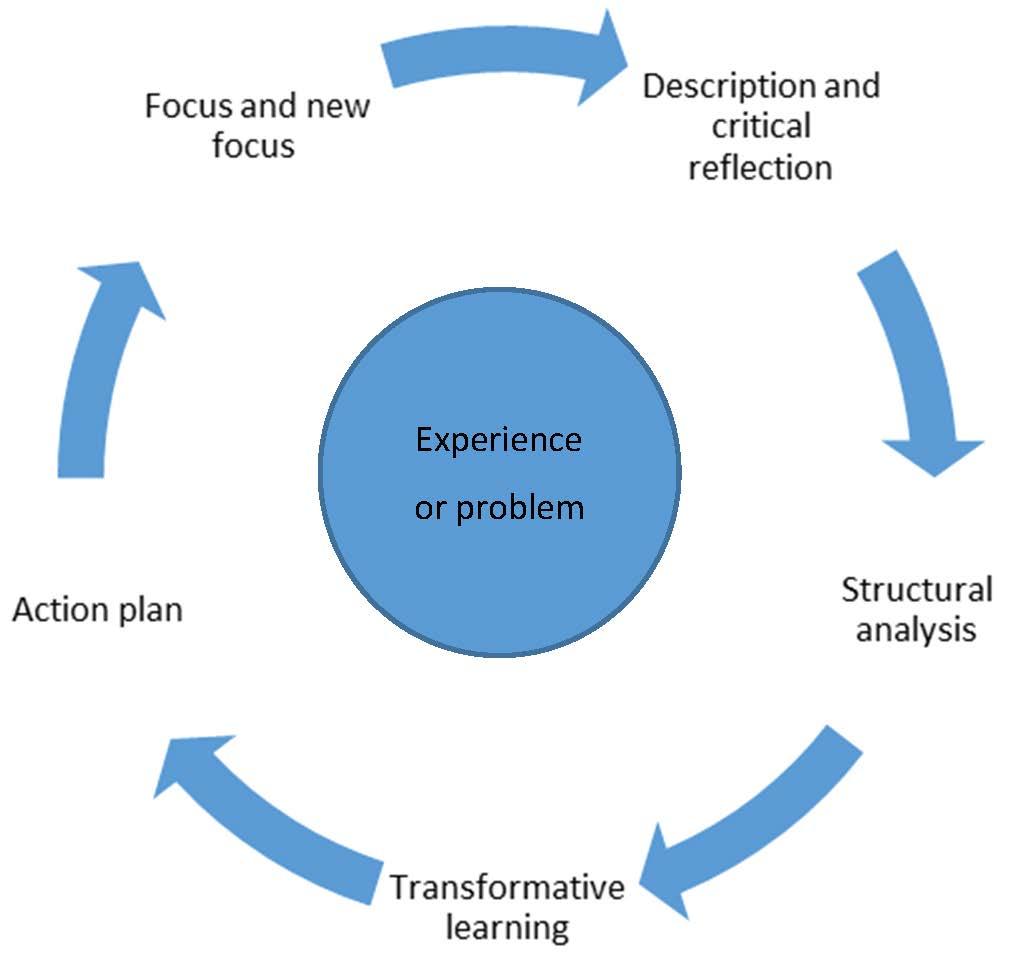

In another context (Tireli and Jacobsen, 2019), we have developed a critical working model that can be used by pedagogues in their work with children and young people (see Figure 1).

The model includes five interconnected steps: the starting point is experience or problem, followed by description and critical reflection and the cycle continues clockwise. It is circular, indicating that work with the model is an ongoing process. Each time the cycle is complete, one faces a new experience or problem, resulting in a new focus. The model is based on Danish experiences with the inclusion paradigm.

Critical didactic analysis model (Source: Tireli and Jacobsen, 2019, p. 63)

The experience or problem that forms the starting point can, for example, be a situation at school where young people talk among themselves about discrimination in education. They do not want to mention it to the teachers, who are thought to be always busy, but they discuss it with the social pedagogues in the after-school programme. The social pedagogue mentions to the teacher that the students are dissatisfied with group divisions in the classroom where the academically weakest students are grouped together, as this makes it clear that young people from minority ethnic communities always end up in this group. The teacher tries to divide the students into mixed groups, and pedagogues and teachers agree to discuss what it means to be academically weak and how the same division of weak and strong also occurs outside school, often without white Danes giving it any thought. The students agree with the teachers and pedagogues to create a project to see whether it is possible to change the division of children and young people, and why it may be difficult to implement without creating major changes in society.

Social pedagogues and teachers decide to initiate a project so that students can examine what it means to come from homes where education is not valued. Does it mean, for example, that young people get no or very little support at home for schoolwork? Young people can talk about examples of a similar division into ‘us and them’ in other contexts. They can decide to inform their younger siblings about their experiences and notice the positive stories that exist.

A description and critical reflection of the situation above means that pedagogues and teachers (and possibly parents) shed light on the content of the project by uncovering the circumstances that can influence practice. How are the elements of the project connected? Who will be affected by the implementation of the project and who will be against it? How can the project relate to other critical initiatives against similar discrimination? These are questions that pedagogues and teachers can discuss together with the students. In this example, social pedagogues facilitate a process whereby young people examine and reflect on what discrimination can cause, why discrimination exists at all and what consequences it has. There are many possibilities for action within the project; social pedagogues together with the students can prepare an interview guide and ask people around them whether they have experienced racism and discrimination and whether they can remember the first time they experienced humiliating divisions in society.

The structural analysis is about linking issues on a level of subjective experience with an overall objective power perspective: Who decides? Where can something be done about discrimination? A structural perspective is also a way to avoid individualising problems and solutions. It is a linking process that must be undertaken together with the students. In this example, it could be a question of what knowledge is needed in society, how ethic minority youths get this knowledge and how young people from all countries can together draw attention to discrimination when they experience it. How do their parents experience discrimination when they are looking for work or accommodation and when they are in public spaces? Social pedagogues can help young people to link micro and macro conditions through such projects.

Transformative learning involves extracting a changed understanding from the analysis. It can be both a joint and an individual learning process. The young people have probably gained knowledge through the project about the connection between their family’s perceptions of school and discrimination and about discrimination in completely different contexts. The result may be that the individuals with an ethnic minority background know the most appropriate way to act the next time they encounter racism in everyday life. Those individual reflections can become the basis for shared learning in the classroom. They can, for example, lead to the students agreeing to create an anti-discrimination page on the school’s and youth club’s digital network, where they collect concrete experiences about discrimination and openly share them. The school and the youth club can perhaps formulate an anti-racism policy and involve other agencies and sectors in the fight against racism.

The action plan must be implemented to ensure that the structural analysis and transformative learning actually lead to change. In this phase, new actions must be initiated that change or dissolve the problem that was originally the starting point of the project. In this example, the students, together with their teachers and social pedagogues, plan to follow up on the project: how do the youth club, school, classrooms and students continue to work with the experiences that their classmates from minority ethnic communities have had? How can the school and youth club help to raise awareness of combating discrimination, regardless of where young people encounter it?

The focus and new focus phase is the opportunity to continue to work with the same or a related theme. Processes become critical if social pedagogues and young people continue to work with them. After going through the different phases of the model as a community, they have gained experience with concrete options for action. These experiences must then lead to a new modified focus or a new problem area. One could imagine that the students discovered that the adults were not as willing to get involved in countering discrimination in everyday life. This could become a new focus: how can they induce the adults to become more involved? It could be an occasion for social pedagogues and teachers to plan a new project – and go through the cycle of the model again.

Community, reflection and action

We described and briefly demonstrated the steps of the model using an example of discrimination among young people at school. Any theme can be addressed using the model – teachers and social pedagogues can test the model many times using different themes; the strength of the model lies not in simply being a work tool, but in developing communities and creating reflection as well as linking reflection to action and mobilisation. In this way, the central elements and values of critical social pedagogy are translated into practice. In the example above, the problem is handled in such a way that the tasks are distributed among the students who are obliged to deliver results and comply with agreements, so that a sense of responsibility and reciprocity in the group arises and is valued. The first and second phases of the model contribute to precisely that, and thus also to a more general sense of community. Using the model with several themes will therefore strengthen responsibility and reciprocity among young people, so that they learn that problems and solutions can be handled together. Community and collective identity are also one of the prerequisites for the formation of critical communities (Diani, 2011). The most important realisation in critical social pedagogy in the twenty-first century is the recognition that no one is alone, and each one is deeply dependent on another.

The structural analysis phase of the model is, on the one hand, a concrete analysis, and on the other hand, a process of reflection and awareness which aims to challenge and develop young people’s understanding of the phenomena they investigate. A shared understanding of phenomena is another prerequisite for critical communities (Diani, 2011). By linking causes with effects, the local perspective with the global, and individual experiences of problems with structural conditions, young people learn that they do not need to feel passive, humiliated or indifferent in the face of discrimination and other challenges in everyday life. They gain a shared awareness that things can be changed.

A distinctive feature of critical social pedagogy is its insistence on actions that change and improve the conditions for all kinds of people. The last two phases of the model – transformative learning, and focus and new focus – are oriented towards actions and activities that the young people have come up with based on their discoveries and knowledge. Teachers and social pedagogues guide these actions, so that students learn to believe that it is possible as future citizens to carry out conscious actions to achieve a better world.

When social pedagogues get involved in communities, it is important that they consider what binds people to a community, and what type of relationships are most dominant and most desirable. They need to know who is represented in communities and whether it is a group that can contribute to anti-radicalisation. Although governments and public authorities strive to prevent polarisation, extremism and radicalisation, problems cannot be solved effectively without the involvement of the local networks and areas frequented by young people at risk of radicalisation.

Extremism and polarisation thrive when local communities do not themselves challenge those who seek to radicalise others. Communities can offer a sense of belonging that provides an alternative to the belonging that extremist groups can use to seduce socially insecure individuals.

Conclusions and perspective

It is through experiments, experiences and counter-narratives that young people at risk of radicalisation learn to defend themselves against the discrimination of the dominant society. In a society where recognition of other people’s lives and opinions is in decline, training and practising social skills can be particularly valuable. People thereby emerge from their own bubble, meet people who are completely different to them, and help those in need. This social engagement breaks down prejudices and strengthens the sense of community. Modernisation and the demand for social mobility in our society have also contributed to the fact that there are few social meeting places where informal support and assistance can be provided. As a result of the detachment from tradition-based communities and the change in values, social commitment is now more closely linked to the development of one’s own personality. One cannot really claim that social skills training in schools and youth clubs can replace the value communities found in radicalised networks. But such training from an early age can increase young people’s self-esteem and at the same time provide knowledge about limitations and shortcomings in the dominant society, as well as letting young people know that their contribution is wanted and valued.

There is only a limited amount of research on the effectiveness of social pedagogical prevention interventions. This applies especially to ‘effect studies’ in social pedagogical youth work in informal environments. Research shows a number of inconsistent definitions, measurements and concepts of changes in mindsets and values, which makes it difficult to compare different projects. Based on some existing projects and programmes that have been implemented, moderate or small effects can be demonstrated (Ohana, 2020). The most promising area of practice seems to be informal activities, but not all forms of informal activism and learning contribute to the inclusion of young people through political engagement. The projects must be based on participants’ critical insight into society’s exclusion mechanisms (Ohana, 2020).

Our proposal includes the participation of young people, the building of non-discriminatory communities and a critical stance on exclusion mechanisms in society. It is thereby hoped that critical social pedagogy will be able to counteract the radicalisation of young people from ethnic minorities. Much depends, however, on the time after the projects come to an end, when it will become apparent what lasting changes have been created in the relationship between the young people and the surrounding society.

Notes

- After 12 satirical cartoons were published in the newspaper Jyllands-Posten in 2005, most of which depicted Muhammad, a holy prophet in the religion of Islam, these cartoon drawings were included in an article on freedom of expression and self-censorship, stating that it was a kick-start to the debate on criticism of Islam and self-censorship. This led to protests by many, not only in Denmark but also around the world, who opposed the use of such imagery. It was reported that some protests became violent and riotous in some countries. ⮭

-

According to Bolig og Planstyrelsen (2020), the criteria for a ghetto area are:

-

•

The proportion of residents aged 18–64 who do not have a job or education exceeds 40 per cent of the average over the past two years

-

•

The proportion of residents convicted of violating the Criminal Code, the Weapons Act or the Act on Intoxicating Substances is at least three times the national average over the past two years

-

•

The proportion of residents aged 30–59 who only have a basic education exceeds 60 per cent of all residents in the same age group

-

•

The share of immigrants and descendants of immigrants exceeds 50 per cent of the residents.

-

•

The average gross income for taxpayers aged 15–64 in the area is less than 55 per cent of the average gross income for the same group in the region.

-

•

- We have looked through various projects connected to the RAN Practitioners. Through the European Commission, RAN connects social workers from across Europe to share knowledge, first-hand experiences and approaches to preventing violent extremism. ⮭

- In the Exit programme, rockers and gang members who want to step out of the criminal environment are offered a coordinated collaborative time course, where they can be offered training, employment, housing, physical and mental condition support, mentoring, a new identity and so on, depending on what is deemed necessary. The Exit process takes place in close cooperation between the Police’s Exit Unit and the Correctional Service and the municipality. ⮭

Declarations and conflicts of interest

Research ethics statement

Not applicable to this article.

Consent for publication statement

Not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest with this work. All efforts to sufficiently anonymise the authors during peer review of this article have been made. The authors declare no further conflicts with this article.

References

Arendt, J. N; Dustmann, C; Ku, H. (2022). Refugee migration and the labor market: Lessons from 40 years of post-arrival policies in Denmark. Study paper 171. The Rockwool Foundation Research Unit.

BL. (2023). Hvem er på listen over udsatte boligområder (den tidligere ghettolisten) 2022?. https://bl.dk/politik-og-analyser/temaer/her-er-listen-over-parallelsamfund/ . Accessed 15 February 2023

Bolig og Planstyrelsen. (2020). Udsatte områder og ghettoområder. https://bpst.dk/da/Bolig/Udsatte-boligomraader/Udsatte-omraader-og-parallelsamfund# . Accessed 27 November 2022

Brønsted, L. B. (2021). Minoritetsdanske drenge som målgruppe i et kriminalitets-forebyggende velfærdsarbejde. Forskning i Pædagogers Profession og Uddannelse 5 (2) : 11. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/fppu.v5i2.129125

Dahlgaard, K. H. (2017). Problematizations in Anti-Radicalization Policy: The case of Aarhus. University of Århus.

Danbolt, M; Myong, L. (2018). Racial turns and returns: Recalibrations of racial exceptionalism in Danish public debates on racism. Racialization, racism, and anti-racism in the Nordic countries. Hervik, P (ed.), Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 39–61.

Diani, M. (2011). The concept of social movement. The Sociological Review 40 (1) : 1–25, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.1992.tb02943.x

Dominelli, L. (2008). Anti-racist social work. Palgrave Macmillan.

Guru, S. (2012). Reflections on research: Families affected by counter-terrorism in the UK. International Social Work 55 (5) : 689–703, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0020872812447625

Herz, M. (2016). Socialt arbete, pedagogik och arbetet mot så kallad våldsbejakakande extremism – en översyn. Rapport 1. Segerstedsinstituttet, Göteborgs Universitet.

Jakobsen, V. (2000). Marginalisering og integration – indvandrere på det danske arbejdsmarked 1980–1996. Tidsskrift for Arbejdsliv 2 (2) : 19. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.7146/tfa.v2i2.108302

Jasko, K; LaFree, G; Kruglanski, A. (2017). Quest for significance and violent extremism: The case of domestic radicalization. Political Psychology 38 (5) : 815–31, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/pops.12376

Jensen, T. G; Weibel, K; Vitus, K. (2017). ‘There is no racism here’: Public discourses on racism, immigrants and integration in Denmark. Patterns of Prejudice 51 (1) : 51–68, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0031322X.2016.1270844

Johansen, M. (2015). Er det tonen, islam eller samfundets skyld?. Jyllands-Posten, February 17 2015

Khader, N. (2015). Mange års arrogant naivisme i forhold til islamisme. Jyllands-Posten, February 20 2015

Larsson, G; Björk, M. (2015). Globala konflikter med lokala konsekvenser, Översikt om utresandeproblematiken. Myndigheten för samhällsskydd och beredskap.

Mørch, S. (2012). Ungdomsliv og bandeunge. Skyggelandet. Jacobsen, I. M. H (ed.), Forfatterne og Syddansk Universitetsforlag, pp. 125–60.

Ohana, Y. (2020). What’s politics got to do with it? European youth work programs and the development of critical youth citizenship, Jugend für Europa. National Agency for the EU programmes Erasmus+.

Olwig, K. F; Pærregaard, K. (2011). ‘Strangers’ in the nation. The question of integration: Immigration, exclusion and the Danish welfare state. Olwig, K. F, Pærregaard, K K (eds.), Cambridge Scholars Publishing, pp. 1–28.

Østergaard, B. (2007). Indvandrerne i Danmarks Historie: Kultur- og religionsmøder. Syddansk Universitetsforlag.

Parallelsamfundsaftalen. (2018). Ét Danmark uden parallelsamfund – Ingen ghettoer i 2030. Regeringen. https://www.regeringen.dk/media/4937/publikation_%C3%A9t-danmark-uden-parallelsamfund.pdf . Accessed 27 November 2022

RAN (Radicalisation Awareness Network). (2017). Families, communities & social care working group. https://home-affairs.ec.europa.eu/networks/radicalisation-awareness-network-ran/topics-and-working-groups/families-communities-social-care-working-group-ran-fcs_en . Accessed 20 October 2022

Regeringen. (2010). Ghettoen tilbage til samfundet – et opgør med parallelsamfund i Danmark. Regeringen. October 2010

Regeringen. (2014). Forebyggelse af radikalisering og ekstremisme: Regeringens handlingsplan. Ministeriet for Born, ligestilling, Integration og Sociale Forhold. https://www.regeringen.dk/media/1289/forebyggelse_af_radikalisering_og_ekstremisme_-_regeringens_handlingsplan.pdf . Accessed 27 November 2022

Tireli, Ü. (2016). Udsathed som dilemma i ungdomsklubbens praksis. Inklusion, udsathed og tværprofessionelt samarbejde. Hamre, B, Larsen, V V (eds.), Frydenlund Academic, pp. 191–209.

Tireli, Ü. (2022). Muslim youth in Denmark. Radicalisation, extremism and social work practice – Minority Muslim youth in the West. Robinson, L, Rafik Gardee, M M (eds.), Routledge, pp. 158–75.

Tireli, Ü; Jacobsen, J. C. (2019). Kritisk pædagogik for pædagoger. Akademisk forlag.