Introduction

In this article, we explore how the citizenship classroom is the ideal space in which features of social pedagogy intersect and interact with young people’s lives in a meaningful way. Citizenship education is an interesting and unique subject in England in which children aged 11–16 years explore social and political issues, then go on to carry out an active citizenship campaign with the intention of making a social impact in their community. The citizenship secondary curriculum in England allows students to engage in contemporary concepts from what is understood as global citizenship, such as climate justice and human rights (Bosio, 2021), and equally engages them in active learning – termed ‘active citizenship’ in the national curriculum (DfE, 2014a) and programmes of study (AQA, 2016; Edexcel, 2016). The citizenship curriculum in England features concepts drawn from both global citizenship and active learning. However, due to the limited scope of this case study-based exploration, we focus only on citizenship education in secondary schools in England.

We explore how the notion of making a positive impact through community action in English citizenship education is echoed in social pedagogy as it aims to bring about positive change for individuals, groups, families and communities (SPPA Charter for the UK and Ireland, 2022). Citizenship education and social pedagogy seem to be intrinsically linked, yet to date there has been almost no literature which brings these two fields together. In this article, we identify links between citizenship education and social pedagogy as practised in England, through exploration of a small number of recent case studies, two within secondary schools and a third with an organisation that works with secondary schools.

We start by focusing on the theoretical underpinning of both citizenship education and social pedagogy, and then highlighting the policy and practice tensions. We then draw on our three recent examples to illustrate how citizenship education and social pedagogy are being embodied and enacted within London schools and with organisations working with those schools and communities. By exploring the relationship between the two disciplines through current examples of good practice, we aim to foster further dialogue between them, encourage deeper exploration as to their alignment and divergence and ultimately to strengthen their integration and give professionals a way forward for effective work with young people – in schools and communities.

Recent historical context of citizenship education and social pedagogy in England

The seeds for citizenship education in England were planted in 1997. At that time, Professor Sir Bernard Crick chaired an Advisory Group on Citizenship and Teaching of Democracy in Schools as requested by the then Labour secretary of state for education, David Blunkett. This was in response to the fear that young people were leaving school with insufficient knowledge and skills to participate in public life, and the ensuing desire to coordinate political and democracy education.

The Advisory Group published the Crick Report (QCA, 1998), which made the case for citizenship as a subject and laid the groundwork of citizenship education to develop across all secondary schools in England. The Crick Report was, and is still, widely recognised as the theoretical underpinning of citizenship as a subject in England. Citizenship education had been made a statutory National Curriculum subject for secondary school students in 2002. This meant that all children aged 11–16 years in state schools would have formalised lessons in a range of topic areas, such as politics and democracy (local, national and international), human rights education, the law, media literacy and the economy. Contemporary topics include climate justice, Black Lives Matter and social inequalities magnified by the Covid-19 pandemic. An element of active citizenship was also introduced; indeed, many schools still conduct a practical active citizenship project in which young people research and start a campaign for an issue experienced by their local community. These active citizenship projects focus on the application of citizenship skills. At the time of the Crick Report, England gained international recognition for being a leader in this progressive subject (Jerome, 2012).

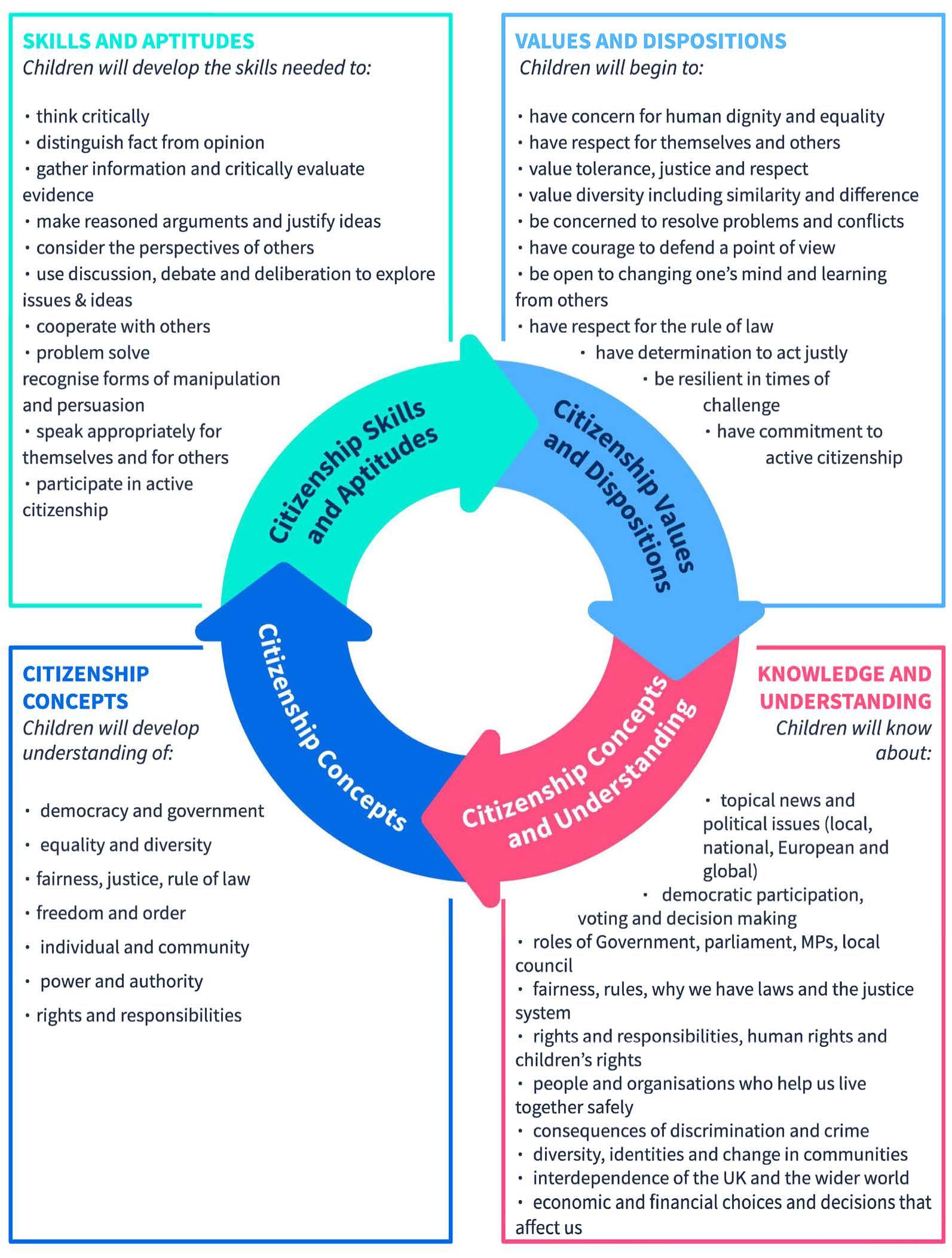

The Association of Citizenship Teaching’s (ACT, 2023a) Citizenship Curriculum Framework illustrates the broad range of concepts, knowledge, skills and values inculcated in citizenship education (see Figure 1).

Lessons in citizenship, when taught well, cover a range of contemporary and often controversial topics, requiring a skilled educator to deliver them effectively. Examples of such lessons might include: ‘What role should tech companies have in policing their platforms in spreading fake news?’; ‘Should monuments to colonial historical figures remain in England?’; ‘Should vaccines be made mandatory?’.

When delivered effectively, citizenship is not only informative and engaging, but can also be empowering to young people, giving them agency and autonomy (Leighton, 2012).

From the inception of citizenship education in 2002 to the present, governments have come and gone and, like most schools in England, the subject has been at the mercy of constantly changing education policy and curriculum reforms (Ball, 2021). This appears to have contributed to citizenship education slipping down the school agenda, perhaps also due to the prevailing neoliberal ideology which has dominated this period. Nonetheless, the subject continues to be commented on by the Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills (Ofsted), the government body that monitors school standards and performance.

Several policy pushes from the Department for Education (DfE) have introduced controversial policy, such as the teaching of fundamental British values, which has attempted to steer citizenship education in a new direction and raised several tensions among parents and staff in schools, as highlighted in Jerome and Elwick (2019). This is also seen as a move away from Crick’s original notion of citizenship education as an inclusive subject which embraces plurality and criticality in communities. In light of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement, which became global in 2020, increasing environmental issues and now growing concerns about the UK economy, citizenship education has undergone a recent resurgence in English schools. This is evidenced by the number of schools signed up to the ACT, the increasing number of teachers training in this specialism and a general appetite from staff and students to teach and learn about our challenging contemporary times. As Bernstein (1970, cited in Reay, 2011) argued, ‘Education cannot compensate for society,’ but schools that aspire to be ‘incubators of democracy’ (p. 2) have a moral duty to try.

Running in parallel to the evolution of citizenship education in England has been the emergence of social pedagogy practice, and to a lesser degree social pedagogy theory and training in the UK. At the time when citizenship education became a statutory National Curriculum subject for secondary school students in 2002, social pedagogy began to appear in public policy documents (DfE, 2003, 2005, 2007). From the late 1990s onwards there had been growing governmental concern about outcomes for disadvantaged children and young people, particularly those in care (looked-after children), and with emphasis on their educational attainment. In a paper on UK social pedagogy, Petrie (2013) argues that the discipline at a policy level ‘can refer to measures that are broadly educational’ (p. 5), asserting that from its inception social pedagogy has attempted to use educational means for social ends. This sentiment in itself aligns very clearly with Crick’s original conception of citizenship education in English schools. In Petrie’s analysis of the principles of social pedagogy practice across the UK’s neighbouring European countries, it is also easy to see synergies with the ACT’s citizenship education ideals, as articulated in their Curriculum Framework. These ideals include active participation and citizenship, children’s education involving their associative lives within their communities and an underpinning by values of relational respect, collaboration and communication (ACT, 2023a; Petrie, 2013).

When the Crick Report was published in 1998, making the case for citizenship education in England, the DfE also commissioned a pilot scheme introducing social pedagogy into children’s residential care. If there was a fear that young people were leaving school with insufficient knowledge and skills to participate in public life, this was truest for those who were in, or had experienced, local authority care, whom research had identified as the most likely to be non-school attenders, excluded and leaving education without qualifications (Department of Health, 2000; Social Exclusion Unit, 1998). This pilot scheme saw qualified social pedagogues from across Europe employed to work in UK residential homes for children (Berridge et al., 2011; Cameron et al., 2011). Social pedagogy practice seemed to offer a broader skillset with more adaptable applicability across the many spheres that shaped children’s lives, which in the context of the shifting of services at that time, followed by the change in administration in 2010, was no doubt welcome. A core concept of social pedagogy is the 3Ps: the professional, personal, private self (Jappe, 2010; ThemPra, 2015). Social pedagogy’s creative and nimble approach to practice, with its focus on direct work, stood in particular contrast to British social work with disadvantaged and at-risk children, which was heavily criticised for having become compliance-driven and proceduralised, with staff lacking the time, skill and knowledge for such complexity. This was summarised in Munro’s (2011) Review of Child Protection in which it became evident that the vast majority of social workers’ time was spent in front of a computer and not with children themselves.

Despite the government’s interest in social pedagogy practice and its implementation in residential care, in addition to similar schemes in foster care training, such as the Head, Heart, Hands programme (Ghate and McDermid, 2016), central government did not adopt social pedagogy in any further usages. As such, it remained active only in pockets of practice across the country, with no uniform or embedded infrastructure. Its growth since the early 2000s has almost exclusively come from grassroots organisations such as ThemPra (founded in 2008), the Social Pedagogy Development Network (established by ThemPra in 2009), the Social Pedagogy Professional Association (SPPA for the UK and Ireland, founded in 2017) and most recently from employer organisations such as Lighthouse Pedagogy Trust, a registered charity. In addition, academic interest has continued within higher education, with new university courses opening and programmes seeking professional endorsement from the SPPA. Similarly, in the case of academia, this growth has centred on pockets of social pedagogy interest, with no uniformity across the nations that SPPA covers (namely England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland). Despite the inconsistency in where and to what extent it is taught, embraced, practised and applied, the UK and Ireland SPPA is generally accepted as the central point of cohesion as regards the discipline’s aims, values and theoretical–practical underpinnings. The SPPA Charter for Social Pedagogy in the UK and Ireland can be seen in Figure 2. Of importance is that the numbering of these statements does not denote any hierarchy or prioritisation.

In this brief overview of the recent British historical context of both social pedagogy and citizenship education over the last two-and-a-half decades, we can already see parallels in both their aims and trajectories in the societal structures that young people move within. We now examine these parallels further by exploring the theoretical and ethical underpinnings of both disciplines.

Theoretical and ethical parallels: social pedagogy and citizenship education

To explore the theoretical and ethical parallels between social pedagogy and citizenship education, we use the Crick Report (QCA, 1998), the key theoretical underpinning of citizenship education in English schools and the Social Pedagogy Charter (SPPA, 2022), which expresses the value base and theoretical–practice approach for social pedagogy in the UK and Ireland.

‘A high-quality citizenship education’, the DfE (2013) in England states, ‘helps to provide pupils with knowledge, skills and understanding to prepare them to play a full and active part in society’ (p.1). This idea of playing a full and active part in society is central to citizenship education and is drawn directly from the Crick Report (QCA, 1998). However, the concept and underpinning of the subject in the Crick Report is further elaborated to consider ‘that citizenship education is education for citizenship, behaving and acting as a citizen, therefore it is not just knowledge of citizenship and civic society; it also implies developing values, skills and understanding’ (QCA, 1998, p. 13). We will therefore consider this broader idea of citizenship education, as originally set out, and which involves three key strands: social and moral responsibility; community involvement; and political literacy (QCA, 1998).

The first idea of social and moral responsibility, as envisioned by the Crick Report, was that responsibility was a moral virtue that implied ‘(a) care for others; (b) premeditation and calculation about what effect actions are likely to have on others; and (c) understanding and care for the consequences’ (QCA, 1998, p. 13). This was underpinned by the idea that children naturally play and work in groups and within communities. Learning, therefore, should be developed not only in the classroom with the students and staff, but also towards and within their communities. This is very similar to the SPPA Charter’s statements about valuing empathy, care and community (see Charter statements 3 and 4 more particularly in Figure 2). Not only do these statements highlight caring, but they also specify that caring is done with meaning and purpose. They speak to intentional caring, and the underpinning of social justice is inherent within them both. As for a definition of social justice, we are drawing on Bell’s (1997) concept of social justice education whereby ‘social justice education is both a process and a goal. The goal of social justice education is full and equal participation of all groups in society that is mutually shaped to meet their needs’ (p. 183). Citizenship education aims to develop a society ‘in which individuals are both self-determining (able to develop their full capacities), and interdependent (capable of interacting democratically with others)’ (Bell, 1997, p. 183). Equally, social justice is a core concept within social pedagogy and is cited within the SPPA (2022) Charter in statement 1 (see Figure 2).

A core difference between citizenship education and social pedagogy is the latter’s emphasis on the lived experiences and life-world orientation (Thiersch, 2006) of those involved, which is of critical importance as a space within which the cause and effect of actions take place. Although there is some space for lived experience to be shared in citizenship education, it certainly does not encourage the same emphasis on life-world orientation and Haltung (Eichsteller, 2010) as seen within social pedagogy practice. The focus in citizenship education, for both the learner and the educator, appears to be directed more towards cause and effect, actions and consequences, whereas social pedagogy places as much emphasis on the holistic context within which those actions take place as it does on the effects themselves. Indeed, citizenship education has been criticised as being a public policy placebo, a tokenistic tool for the government to demonstrate that it is engaging with issues of social justice (such as institutionalised racism), when in fact it is limited in its contextualised impact (Gillborn, 2006).

The second concept of community involvement within citizenship education as posited in the Crick Report considers ‘the development of personal and social skills through projects linking schools and the community, volunteering and the involvement of pupils in the development of school rules and policies’ (QCA, 1998, p. 4). Here we see clear consideration that skills and understanding can be drawn from both inside and outside the formal curriculum and classroom. This notion that citizenship education develops students engaged within their communities is a central aim of the subject. This key goal is explicitly stated in the Crick Report: students should be ‘becoming helpfully involved in the life and concerns of their communities, including learning through community involvement and service to the community’ (QCA, 1998, p. 12). This aligns with SPPA Charter’s statements 2 and 12 (see Figure 2). A key difference, again, is the lack of emphasis on holistic value-context and Haltung (Eichsteller, 2010) in citizenship education, which social pedagogy places at the centre of practice.

The latter sentiment expressed in statement 12 speaks to citizenship education’s third and final strand: political literacy. In the Crick Report the term ‘political literacy’ was carefully selected, rather than ‘political knowledge’, in order to encompass the idea of wider public life and an ability to participate therein. This involves students ‘learning about and how to make themselves effective in public life through knowledge, skills and values QCA (1998). This encompassed genuine knowledge of and a readiness for dealing with ‘conflict resolution and decision-making’ (QCA, 1998, p. 13) related to economic and social problems they may encounter in life’. At the heart of this branch of citizenship education is the desire to equip students with the knowledge, skills and readiness to participate in the world of work and society at large. This includes understanding political systems, economics and taking a critically informed position regarding how society works, how economies work, how they are structured and how to facilitate positive change within these structures. Equally, the SPPA (2022) Charter also reads: ‘We believe in the social and political agency of individuals and groups to make significant choices about their lives and to contribute to their community. Social Pedagogy believes in practice that engages with the whole person and the networks, systems, and communities that impact upon their lives’ (n.p.; see also statement 7 in Figure 2). Both social pedagogy and citizenship education place value not only on an understanding of wider socio-political contexts and their impact, but on individuals’ ability to apply this understanding critically and in a participatory way within their communities, with the goal of effecting positive change.

Citizenship education through its three strands at its best encourages a ‘more interactive role between schools, local communities and youth organisations’ (QCA, 1998, p. 9), encompassing a very useful, important and holistic education. The aim of citizenship education is to equip students to play a full and active part of society (DfE, 2013). The advantages of citizenship education as theorised by the combination of these three strands is beneficial for all: students and teachers, schools and communities and as such wider society. In this way citizenship education should empower students to ‘participate in society effectively as active, informed, critical and responsible citizens’ (QCA, 1998, p. 9). Equally, the work and experiences of those engaged in social pedagogy, holistically embodying the values as outlined in the SPPA Charter, should also enable people to participate effectively, inclusively and critically in their own communities and in the context of others’ communities, therefore benefiting wider society. Indeed, social pedagogy in the UK has been described as having the potential to challenge current social structures (Hatton, 2013). There are clear theoretical and ethical parallels between social pedagogy and citizenship education, as well as some diverging emphases within them.

Policy and practice tensions: citizenship education and social pedagogy

We will now consider the extent to which the teacher can deploy a social pedagogical approach in delivering citizenship education in English schools in the current socio-political context, given policy tensions in the education system and the lack of a coherent understanding or application of social pedagogy across the country.

There has been a wave of neoliberal educational policy initiatives over the past 15 years that have hindered the trajectory of citizenship education in England, as set out by the Crick Report (QCA, 1998). The neoliberal education policy seeds were seemingly planted in the early 2000s under the Labour government of the time (Ball, 2021). The first direct policy implication came through the Academies Act (DfE, 2010a), passed by a Conservative/Liberal Democratic coalition government; this Act had considerable consequences on citizenship education provision. It meant that several secondary schools converted into academies and as a result were given greater flexibility and freedom over curriculum choice, but this was leveraged with much stricter accountability measures. School grades became high currency, as they formed a key line of comparison and were under direct scrutiny from Ofsted, the school inspectorate system. The shift in accountability to grades coupled with the freedom over curriculum meant that citizenship education take-up in schools dropped significantly. Prior to this, citizenship education had to be delivered in every school in a coordinated way. Consequently, schools began to re-prioritise traditional subjects and give less curriculum time to deliver citizenship and other arts and humanities subjects. Many schools began to deliver the subject through whole-school assemblies (tending to be delivered didactically) or form/pastoral time (short time at the start of the day when the register is taken) and many other ways which slowed down the impact and progress the subject was making in the lives of students and their communities. Despite this change, there was a small but strong core of secondary schools who continued to keep citizenship education on their curriculum.

A second policy that hindered the engagement with citizenship education in English schools came in the government’s 2015 GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) reforms (DfE, 2014b). GCSE is the public qualification that most children in England gain at the age of 16. At the time in post, Conservative Education Minister Michael Gove, under the auspices of raising standards (DfE, 2010b), made significant changes to GCSEs. A key change was the reduction in, and limiting of, the coursework or fieldwork component of the GCSE qualification; this was in favour of an exam-based, knowledge-rich, didactic curriculum (DfE, 2010b). As such, the time spent on active citizenship, a field-based component of citizenship education in which students identify, research and raise awareness, and campaign for a local issue affecting their community, was reduced substantially. The active citizenship component of the subject formed an integral part of the learning that brought together students, staff and the community, and which embodied the community social action which characterises social pedagogy (Storø, 2013). Policy change meant that the impact of this active and applied citizenship project was reduced considerably, thereby minimising the subject’s participatory links within communities. The DfE’s rationale for the education reform of the GCSE was to become more engaging and worthwhile to teach and study, as well as more resilient and respected (DfE, 2014b). Nonetheless, these changes essentially led to the squeezing out of creative subjects from the curriculum, leading to a narrower, more conservative and traditional subject profile within schools (Maguire et al., 2015). Subjects such as art, performing arts, media studies and citizenship education suffered as a result, and with them schools’ community links via public performance, public debate and other participatory engagement events and collaborations.

A third consideration concerns guidance entitled Political Impartiality in Schools (DfE, 2022), which serves as a reminder to teachers to avoid teaching political issues in a one-sided manner. While this does not explicitly dictate that the teacher’s personal view should not be shared, it certainly creates a tension with the social pedagogy practice of applying the 3Ps (Jappe, 2010; ThemPra, 2015). Indeed, in 2020, when the first version of this guidance was published, it sparked fierce criticism as it led to feelings of surveillance and dictatorship over how and what staff should teach and say in their classrooms. The guidance went on to discuss what resources teachers should avoid; for example, Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion were explicitly cited as groups whose resources or ideologies should not be promoted. The government has since reviewed this guidance, under threat of legal action by the Coalition of Anti-Racist Educators (CARE). Disapproval of the guidance was also supported by several teaching unions and other educational organisations, chief among them ACT. Despite its revision, it still serves as a deterrent for teachers, rendering them reticent to share their own political views, something which is incongruent with social pedagogy’s theory and practice of the 3Ps. It brings a sense of reluctance to engage young people in controversial and sensitive topics in the classroom, subjects which directly affect those young people in the context in which they are living and learning. And yet this active debate, participation, community research and activism are at the very core of citizenship education both as a subject and as a social pedagogical endeavour.

Despite these policy and guidance changes, there seems nonetheless to have been a resurgence in the subject in the past few years in England. In light of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Black Lives Matter movement following George Floyd’s murder in 2020, increasing awareness of the climate crisis, and a generation of students who were leaving school with limited engagement in social and political issues, there has been a recent trend to revert back to the subject. Further to this, post-pandemic there seems to have been a shift in collective consciousness in rethinking the place of schools and of education more broadly within society. The school is more than just a place that serves qualifications; it should be a place in which young people actively learn about their world in an informed and critical way and participate in that world for individual and collective benefit. This is a sentiment that is at the heart of citizenship education, and at the core of social pedagogy, which is often described as being where education and care meet (Cameron and Moss, 2011).

As outlined above, neoliberal policies passed under a Conservative government led directly to disengagement with citizenship education in schools in England, and the number of schools delivering citizenship in a structured and coordinated way, as the Crick Report suggested, dwindled between 2010 and 2013, as evidenced by the number of students sitting citizenship exams in England (Ofqual, 2023). More recently, however, there has been a growing appetite for citizenship education among students, schools and teachers. Indeed, evidence of the subject’s resurgence can be seen in the increase in schools’ memberships to the subject association, in the number of citizenship trainee teacher applications and in the rising numbers of students sitting citizenship exams (Ofqual, 2023). Moreover, the political movements and global, collective experiences over these last three years, which have laid bare the realities of structural inequalities (Fiske et al., 2022), seem to have motivated a new generation of young people keen to understand and actively engage in the world in which they live, and triggered a hunger from new teachers coming into the profession who want to teach young people how to do this. This trend seems to be supported by the increased number of citizenship education GCSEs taken up by students (Ofqual, 2023).

In summary, government policy and guidance changes have created challenges to the way in which teachers can deploy social pedagogical practices in citizenship teaching. Parallel to this, the lack of consistent policy and application of social pedagogy by the government has hindered the embedding of this discipline within education and care for young people. Nonetheless, citizenship teachers can, and often do, deploy a social pedagogical approach to engaging students in such topics, as we will illustrate in the following case examples of London schools and affiliated organisations.

Citizenship education and social pedagogy in action: case studies with London school students

In the previous sections we have reviewed the recent context of social pedagogy and citizenship education in England, outlined some key ethical and theoretical parallels and differences between them and explored the policy tensions within which the two disciplines currently exist. We will now illustrate examples which draw clearly on citizenship education and social pedagogy in practice to demonstrate the exemplary work that educators and students are achieving in this field.

Battle of Ideas: community debates

The first example is from a state comprehensive school in inner-city London. The school has a very diverse student intake, with more than half of its students being on Pupil Premium (that is, the funding to improve education outcomes for disadvantaged pupils in schools in England), and a high number being ESL (English as a Second Language) students. The Head of Citizenship has been at the school for more than 10 years and is well known in the community and with local families.

The example we will draw on is a Battle of Ideas day run by students and staff on a Saturday. Students decided on a range of subjects they felt were important to them, but that were not covered in the school curriculum. The teachers and students agreed the topics and organised formal debates and round-table discussions to take place on the day. Students spent time researching and developing their speeches and arguments for the workshops. On the Saturday that the Battle of Ideas day was run, parents, staff, students and members of the local community were all invited to attend and take part. The audience included local shopkeepers, café workers, barbers, imams and priests. The students took to the stage and passionately explored, discussed and listened to fellow peers as they debated the key ideas they had agreed were relevant to them. A topics and programme outline can be seen in Table 1.

Programme outline of the Battle of Ideas day (Source: anonymised London secondary school).

| 09:00–09:20 | Welcome and registration |

| 09:20–09:45 | Introduction to the day – guest speaker |

| 10:00–10:45 | EDUCATION: Does creative arts have a role in creating community cohesion? RELIGION & MORALITY: What is Christianity’s role in the modern world? SOCIETY ISSUES: Genetic advantage: What’s the deal with gender representations in sport? CONTEMPORARY ISSUES: Is mental health the biggest issue facing the UK? |

| 10:45–11:00 | Break |

| 11:00–11:45 | EDUCATION: Is the National Curriculum fit for purpose? RELIGION & MORALITY: Addey’s changemakers: can young people really change society? SOCIETY ISSUES: Does Drill music lead to violence and negative perceptions of Black youth? CONTEMPORARY ISSUES: What should the UK Budget be spent on? |

| 11:45–12:30 | Lunch |

| 12:30–13:15 | EDUCATION: What is the impact of the education system on teenage mental health? RELIGION & MORALITY: What is the Islamic experience in China? SOCIETY ISSUES: Does discrimination still exist in the UK today? CONTEMPORARY ISSUES: Should cannabis be legalised for medical purposes? |

| 13:15–13:30 | Break |

| 13:30–14:00 | Performance and closing speeches |

This whole community approach, in which students co-created debates with their teachers and explored local issues with peers, elders and community leaders, is an example of how social pedagogical methods are being used in schools in England by some teachers, despite education policy constraints, and despite social pedagogy being neither endorsed nor formally supported by the government. This is a real example of citizenship education and social pedagogy in action. Active citizenship campaigns are still run by students every year at this school as a result of the success of this Battle of Ideas programme.

Rights and responsibilities: active citizenship campaign

The second example is from another inner-city London school. This school can also be classified as having a socially diverse student intake, with more than half the number of students coming from lower-income households and accessing free school meals. In addition, there are a large number of students with English as an additional language, and lastly there is an above national average number of students with special educational needs or disability. In this particular case, the citizenship teacher was given a group of students which consisted of only seven boys aged 14–15 years who were placed into the citizenship GCSE class. These boys did not actively choose to study the subject, rather the school had deemed them ‘at risk’ of failing or not completing what is seen as more traditional academic subjects. This links back to the notion of how citizenship during this time was seen as low status; schools began to de-prioritise citizenship education in favour of more traditional subjects as part of the Academies Act (DfE, 2010a). The subject arguably took on the status of being a ‘dumping ground’ for those students not deemed academically bright enough for the more traditional academic subjects. The teacher at this particular school recounted how many of the other staff and senior management deemed these pupils ‘unteachable’. As a result, this small group of boys who had poor behaviour, low attendance and adverse school disciplinary records were placed in the citizenship education class.

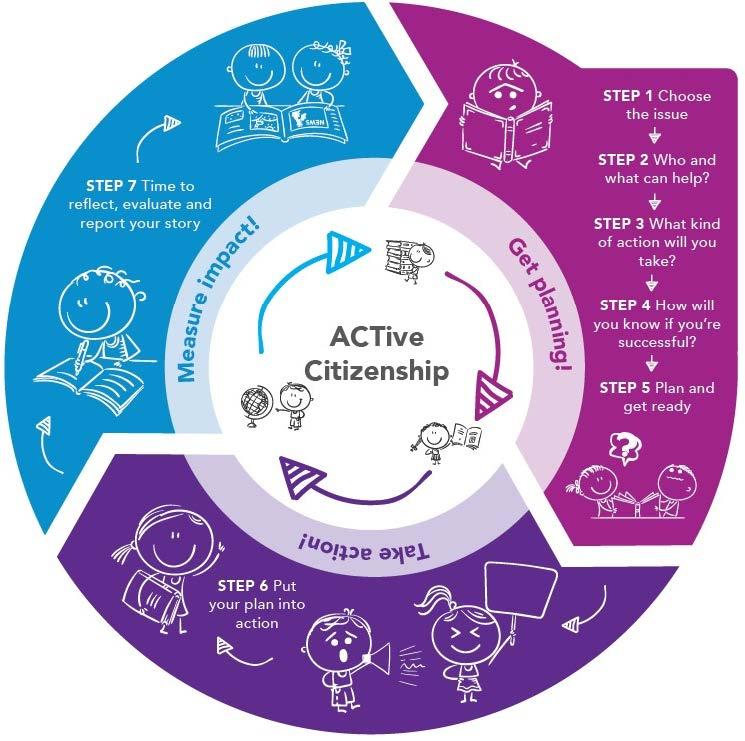

The active citizenship component of the course requires students to identify, research and then take citizenship action on an issue of their choosing. It is this active citizenship component that most faithfully aligns with a social pedagogical approach to participatory work with young people (see Figure 3).

In this case, the boys categorically agreed that for their ACTive Citizenship project ‘Stop and search’ legislation and rights was a key issue in their local community that was impacting on their lives. ‘Stop and search’ is a controversial police power in the UK that gives officers the right to stop and search people on ‘reasonable grounds’, or in many cases without grounds if approved by a senior officer, and is considered to have increased racial profiling (Borooah, 2011). This rights issue united and motivated the students to begin their research on the subject. As part of this process, the teacher arranged for a meeting and interview with a local police officer. During this meeting, the students asked some very difficult questions and shared personal experiences of being stopped and searched themselves. The police officer not only shared local crime figures, but also recounted her personal experiences, engaging with the young people in a way that embodied the social pedagogical approach of the 3Ps (Jappe, 2010; ThemPra, 2015). The officer expressed to the citizenship teacher that she had found the experience challenging, yet deeply rewarding. This sparked an interesting moment of empathy in both the students and the police officer, a moment of mutual understanding of each other’s position and perspective, of each other’s life-world orientation (Thiersch, 2006).

Next, the students started a campaign to take action and educate their peers not only on key points of the law, but also on students’ rights. The seven boys designed 10-minute workshops and went into other lessons to deliver these to their peers, educating pupils about ‘Stop and search’ rights. This ultimately culminated in the boys delivering a whole-school assembly speaking to an audience of over 700 students and staff and educating them on this important issue. The boys, who had been seen as unmotivated and were deemed ‘unteachable’ by some staff, all passed the citizenship GCSE, many with a very strong grade. Real victory for the citizenship teacher in this instance was seeing the students’ transformation. Here, the teacher recounts how this was to remain one of the most rewarding and memorable accomplishments in her teaching career:

This Active Citizenship campaign, involving students, teachers, and the police, embodied several elements of social pedagogical practice and allowed these young people to develop skills, confidence and more meaningful engagement with education. This school continues to have a strong emphasis on teaching local Black history, rooted in the community, which stems from the success of this community engagement and activism that this small group of students initiated.

Feltham Convening Partnership: summer research programme

Feltham Convening Partnership (FCP) is a collective impact initiative that aims to improve outcomes for children and young people in Feltham, south-west London. Among its far-reaching work and collaborations, FCP has a partnership with a social pedagogy degree at Kingston University that focuses on working with children and young people. Although none of the students who took part in the summer research programme (Figure 4) – our third and final case study – are studying citizenship as a subject, this example clearly illustrates the type of active citizenship using a social pedagogical approach that can engage young people in their own education and in their own communities. FCP works with several secondary schools within the area it covers in south-west London.

FCP arranged the summer research programme to engage secondary school students in active community research in July and August 2022. Fifteen local young people who attend secondary schools across Feltham were chosen to take part. This included students who were at risk of becoming NEET (Not in Employment, Education or Training), from Black and minority ethnic backgrounds, or those with special educational needs. Students had to answer two questions in order to take part: What challenges do young people face today in Feltham? What change would you like to see in your community and why?

Key themes emerged around mental health challenges in young people, particularly post-Covid-19; the lack of knowledge of and awareness on mental health; the lack of mental health support for young people; insufficient spaces for young people to socialise; and a lack of preventative mental health support. As such, the students chose to focus their research projects on young people’s mental health in Feltham. To complement this community action research, they also took part in a tour of Parliament with their local MP and received training from a community organiser from Citizens UK. For their research, school students worked in groups to collect and analyse data and to summarise key findings, with support from three mentors completing postgraduate studies at Kingston University and Royal Holloway University. The research programme culminated in the young people delivering a 10-minute presentation of their projects to a panel with representation from FCP, the local authority, Kingston University, Royal Holloway University, the Reach Children’s Hub and other community partners. Their projects resulted in several actions, including two local petitions, a leafleting campaign and a blog.

This final example demonstrates how organisations like FCP are working with schools, communities, local services, local authorities and local universities to engage young people in community research and action on issues chosen by, and impacting, those young people themselves. At the heart of this work is a non-hierarchical approach to community action, an act of citizenship that embodies social pedagogy. This is demonstrated by testimonials from community members: ‘just love the way you are embedding community action into the youngsters, brilliant ethos/skill to take through life’ (local community member, FCP, 2022). This project will continue to take place each summer, convened by FCP, until at least 2026. While these students were not explicitly studying citizenship education, it is clear to see how their field trips, community research and resulting activist campaigns embody both the ethos and the practicalities of citizenship education, in particular the active citizenship element of the subject.

Conclusion and a call to action

In this article we have drawn on two distinct yet similar fields: citizenship education and social pedagogy, demonstrating how they coexist organically and can complement each other in an integrated manner when working with young people. Given the often topical, sensitive and controversial subjects that citizenship covers in the curriculum, it stands to reason that it requires a skilled and empathic educator to effectively engage young people in it meaningfully. Through the exploration of a small number of case studies, we argue that this skill and mindset is one which sits closely within the key features of social pedagogy practice. Citizenship teachers are trained in the teaching of controversial issues; however, these very much take the form of deploying techniques such as positioning the teacher’s role in stimulating discussion, or in acting as a referee for student discussion (Council of Europe, 2015). Other guidance serves to remind teachers of their lawful and professional duties (DfE, 2022; NASUWT, 2023). There is also a wealth of research around taking a children’s rights-based approach to teaching (Jerome and Starkey, 2022; Osler and Starkey, 2010; Osler and Zhu, 2011), which is again helpful in considering the role of the teacher within a rights-based perspective. However, we believe that by drawing on aspects of social pedagogy in particular, a deeper pedagogic dimension is opened up for educators, through which they can meaningfully engage and support the learning of students in citizenship education and related citizenship activities, such as community research and activism.

In his seminal text Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire (1970) challenged thinking about education as being politically neutral; he argued that it has inherent value positions and advocated for a new model of critical pedagogy in which educators and students learn together in a dialogical relationship (Alexander, 2020). This idea is developed further by Giroux (2011), who argues that in recent times neoliberal forces have reduced education to training, positioning students as customers. Giroux encourages us to think about how we take into consideration the experiences and feelings of students, their Haltung and life-world orientation in effect (Eichsteller, 2010; Thiersch, 2006). To demonstrate how social pedagogy is already being enacted to some degree in citizenship education, we have highlighted how secondary school teachers and others have begun to draw on elements of social pedagogy as a form of co-creation, challenging the neoliberal idea of students as consumers of education (Giroux, 2011). Interestingly, the educators in our case studies have developed this practice without any specific training or explicit prior experience in applying social pedagogy. Even for FCP, its collaboration with a social pedagogy university degree constitutes its very first alliance with social pedagogy.

We believe that citizenship education, when taught well, encapsulates features of social pedagogy. Indeed, as Hämäläinen (2003) argued, ‘the social pedagogical perspective was based on attempts to find educational solutions to social problems’ (p. 71). We have outlined the similarities in theoretical underpinnings of the disciplines by examining the Crick Report (QCA, 1998) and the SPPA Charter (SPPA, 2022). The clear central theme within both is the underlying social justice aim of trying to make a positive impact for individuals, groups, families and communities (Bell, 1997). In light of social pedagogy and citizenship education sharing this key aim and value, it is surprising that there is little literature connecting these two fields which have clear crossovers in both theory and practice.

We have outlined the policy tensions imposed on citizenship education, which have limited the subject, as well as the lack of consistent policy support for social pedagogy, which has equally limited the application of this practice. Despite this, citizenship education as a subject appears to be on the rise, as does social pedagogy practice and training. Furthermore, as seen through the case study examples illustrated in this article, citizenship education which embodies social pedagogy appears to be alive and well, and can have a positive impact on the lives of children and their communities. As stated in statement 13 of SPPA (2022) Charter: ‘We believe in the social and political agency of individuals and groups to make significant choices about their lives and to contribute to their community’ (n.p.). The British sociologist Reay (2011, citing Bernstein, 1970) writes that although ‘education cannot compensate for society’, schools that aspire to be ‘incubators of democracy’ have a moral duty to try (p. 2). We believe that citizenship education and social pedagogy, when combined, offer a clear attempt to address this and a coherent vehicle through which to achieve it; we call on all educators (in schools, residential care homes and beyond the school gates), and indeed all those who work with young people, to consider these disciplines as powerfully integrated, and as offering great potential for educating and emancipating society’s young people.

Declarations and conflicts of interest

Research ethics statement

Not applicable to this article.

Consent for publication statement

The examples drawn on in this article are from partnership schools whose names have not been disclosed, and consent for words and images from those involved has been granted to the authors. The authors declare that research participants’ informed consent to publication of findings – including photos, videos and any personal or identifiable information – was secured prior to publication

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declare the following interests: Yvalia Febrer is on the Editorial Board of International Journal of Social Pedagogy in which this article is published and a Trustee of the SPPA for the UK and Ireland. She is also the Course Leader at Kingston University for the Social Pedagogy Undergraduate programme that is partnered with FCP. All efforts to sufficiently anonymise the authors during peer review of this article have been made. The authors declare no further conflicts with this article.

References

Association of Citizenship Teaching. (2023a). Citizenship Curriculum Framework. https://www.teachingcitizenship.org.uk/resource/active-citizenship-toolkit-award-resources/ . Accessed 11 May 2023

Association of Citizenship Teaching. (2023b). ACTive Citizenship, Key Stage 3 Toolkit and Award Resources. https://www.teachingcitizenship.org.uk/resource/active-citizenship-key-stage-3-toolkit-award-resources/ . Accessed 11 May 2023

Alexander, R. (2020). A dialogic teaching companion. Routledge, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9781351040143

AQA.org.uk. (2016). GCSE Citizenship Studies. https://filestore.aqa.org.uk/resources/citizenship/specifications/AQA-8100-SP-2016.PDF . Accessed 18 February 2023

Ball, S. J. (2021). The education debate. Policy Press.

Bell, L. (1997). Theoretical foundations for social justice education. Teaching for diversity and social justice: A sourcebook. Adams, M, Griffin, P; P and Bell, L L (eds.), Routledge.

Bernstein, B. (1970). Education cannot compensate for society. New Society 15 (387) : 344–7.

Berridge, D; Biehal, N; Lutman, E; Henry, L; Palomares, M. (2011). Raising the bar? Evaluation of the Social Pedagogy Pilot Programme in residential children’s homes. Research Report DfE-RR148. Department for Education.

Borooah, V. K. (2011). Racial disparity in police stop and searches in England and Wales. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 27 (4) : 453–73, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10940-011-9131-0

Bosio, E. (2021). Conversations on global citizenship education: Perspectives on research, teaching, and learning in higher education. Routledge.

Cameron, C; Moss, P. (2011). Social pedagogy and working with children and young people: Where care and education meet. Jessica Kingsley.

Cameron, C; Petrie, P; Wigfall, V; Kleipoedszus, S; Jasper, A. (2011). Final report of the social pedagogy pilot programme: development and implementation. Thomas Coram Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London.

Council of Europe. (2015). Teaching controversial issues. https://edoc.coe.int/en/human-rights-democratic-citizenship-and-interculturalism/7738-teaching-controversial-issues.html . Accessed 20 February 2023

Department of Health. (2000). The Children Act report 1995–1999. HM Stationery Office.

Department for Education and Skills. (2003). Every child matters. HM Stationery Office.

Department for Education and Skills. (2005). Children’s workforce consultation paper. HM Stationery Office.

Department for Education and Skills. (2007). Care matters: Time for change. HM Stationery Office.

Department for Education and Skills. (2010a). Academies Act 2010. DfE.

Department for Education and Skills. (2010b). The importance of teaching: the schools white paper 2010. HM Stationery Office.

Department for Education and Skills. (2013). The National Curriculum in England: Key stages 3 and 4 framework document. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-secondary-curriculum . Accessed 19 February 2023

Department for Education and Skills. (2014a). The National Curriculum in England: Key stages 3 and 4 framework document. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-curriculum-in-england-secondary-curriculum . Accessed 19 February 2023

Department for Education and The Rt Hon Michael Gove. (2014b). GCSE and A level reform. https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/gcse-and-a-level-reform . Accessed 12 October 2022

Department for Education. (2022). Political impartiality in schools. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/political-impartiality-in-schools/political-impartiality-in-schools . Accessed 20 February 2023

Edexcel. (2016). GSCE Citizenship Studies [online]. https://qualifications.pearson.com/en/qualifications/edexcel-gcses/citizenship-studies-2016.html . Accessed 18 February 2023

Eichsteller, G. (2010). The notion of ‘Haltung’ in social pedagogy. Children Webmag. https://thetcj.org/in-residence/the-notion-of-haltung-in-social-pedagogy . Accessed 11 May 2023

Feltham Convening Partnership. (2022). Summer research programme. August 2022

Fiske, A; Galasso, I; Eichinger, J; McLennan, S; Radhuber, I; Zimmermann, B; Prainsack, B. (2022). The second pandemic: Examining structural inequality through reverberations of COVID-19 in Europe. Social Science & Medicine 292 : 114634. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114634

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Seabury Press.

Ghate, D; McDermid, S. (2016). Implementing Head, Heart, Hands: Evaluation of the implementation process of a demonstration programme to introduce social pedagogy into foster care in England and Scotland. Main report, Loughborough. The Colebrook Centre for Evidence and Implementation and CCFR, Loughborough University.

Gillborn, D. (2006). Citizenship education as placebo: ‘Standards’, institutional racism and education policy. Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 1 (1) : 83–104, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1746197906060715

Giroux, H. A. (2011). On critical pedagogy. Continuum International.

Hämäläinen, J. (2003). The concept of social pedagogy in the field of social work. Journal of Social Work 3 (1) : 69–80, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1468017303003001005

Hatton, K. (2013). Social pedagogy in the UK: Theory and practice. Russell House.

Jappe, E. (2010). Handbog for paedagogstuderende. Frydenlund.

Jerome, L. (2012). England’s citizenship education experiment: State, school and student perspectives. Bloomsbury.

Jerome, L; Elwick, A. (2019). Identifying an educational response to the Prevent policy. British Journal of Educational Studies 67 (1) : 97–114, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2017.1415295

Jerome, L; Starkey, H. (2022). Developing children’s agency within a children’s rights education framework: 10 propositions. Education 3-13 50 (4) : 439–51, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2022.2052233

Leighton, R. (2012). Teaching citizenship education: A radical approach. Continuum International Pub. Group.

Maguire, M; Braun, A; Ball, S. (2015). ‘Where you stand depends on where you sit’: The social construction of policy enactments in the (English) secondary school. Discourse: Studies in the cultural politics of education 36 (4) : 485–99, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2014.977022

Munro, E. (2011). The Munro Review of child protection. Final report, a child-centred system. TSO.

NASUWT. (2023). Political impartiality in schools (England). https://www.nasuwt.org.uk/advice/in-the-classroom/curriculum/curriculum-qualifications-england-/political-impartiality-in-schools-england.html . Accessed 20 February 2023

Ofqual. (2023). GCSE outcomes in England. https://analytics.ofqual.gov.uk/apps/GCSE/Outcomes_Link1/ . Accessed 20 February 2023

Osler, A; Starkey, H. (2010). Teachers and Human Rights Education. Trentham Books.

Osler, A; Zhu, J. (2011). Narratives in teaching and research for justice and human rights. education. Citizenship and Social Justice 6 : 223–35, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/1746197911417414

Petrie, P. (2013). Social pedagogy in the UK: Gaining a firm foothold?. Education Policy Analysis Archives 21 (37) : 1–13, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v21n37.2013

Qualifications and Curriculum Authority. (1998). Education for citizenship and the teaching of democracy in schools, Final report. September 22 1998

Reay, D. (2011). Schooling for democracy: A common school and a common university? A response to “Schooling for Democracy”. Democracy and Education 19 (1) : 6.

Social Exclusion Unit. (1998). Truancy and school exclusion. SEU.

Social Pedagogy Professional Association. (2022). A charter for social pedagogy in the UK and Ireland. https://sppa-uk.org/governance/social-pedagogy-charter/ . Accessed 11 May 2023

Storø, J. (2013). Practical social pedagogy: Theories, values and tools for working with children and young people. Policy Press.

ThemPra. (2015). The three Ps. https://www.thempra.org.uk/social-pedagogy/key-concepts-in-social-pedagogy/the-3-ps/ . Accessed 11 May 2023

Thiersch, H. (2006). The experience of reality. Perspectives of an everyday-oriented social pedagogy. 2nd supplementary ed. Juventa.