Introduction: Creative mentoring and social pedagogy

Creative mentoring is an innovative service to help support vulnerable children living in care. The service is delivered through Derbyshire County Council’s Virtual School, made up of a team of education professionals who work alongside schools. It has been developed to offer the best possible provision and support for children and young people in the council’s care. The school is described as ‘virtual’ because it does not occupy an actual building but is made up of tutors and mentors that move to wherever the child is, either in school or at their foster home. Our work supports engagement and participation by building a personalised, unique provision around the child.

Supporting creativity through the mentoring service links to social pedagogical concepts via relationship building, empowerment and holistic work across all areas of education and care. Creative mentoring works outside a deficit model and attends to an individual’s strengths and potential, providing a positive and optimistic approach to supporting the whole person. Our service is offered to children and young people through a referral system, mostly from schools, but also through social workers, care staff and education support officers who know the children and are aware of the service. The objective of the service is to support wellbeing through a creative learning journey, leading to re-engagement with education, employment and training. Creative mentors are artists and creative professionals employed by the council on a freelance basis. Mentors have backgrounds in the arts and across many creative industries such as sculpture, woodwork, textiles, music, dance and performing arts. Creative mentors are theatre practitioners, ceramicists, film makers, photographers and visual artists such as painters and makers. The recruitment process ensures that the artists also have appropriate experience of working with and alongside children and young people.

The creative mentor service is well placed to offer a range of creative interventions that can match with the young person’s interests. Diversity is key, and if we find that a young person with whom we are working needs the support that another mentor can offer, we will introduce that practitioner to them. Resourcefulness and flexibility are essential parts of our mentor work. It is not only the work that creative mentors do with the young people that is ‘creative’; so too are the ways in which we offer the best kind of support for the individual. Seeing the potential in an art form with which a young person engages can then extend into a more powerful experience. For example, one young person that I worked with struggled in a classroom environment; after trying lots of different creative mediums we found that he flourished when working with clay (Figure 1). Clay was something he could shape and move just as he liked; he could pummel it and tear it, smooth it and shape it. He had complete control of the medium. We then found that he was a natural on the potter’s wheel: the activity provided an opportunity for focus and complete absorption. Each week the battle to control the clay was almost always won. ‘At last’, he cried in delight, ‘something I’m good at’. He made one hundred clay pots that summer in a sponsored event at school to raise money for a children’s hospital, gaining respect and admiration from teachers, peers and family members (Figure 2). Problem solving, finding the potential in ideas and ways of working, seeing things from a different perspective and being creative are all part of our practice as artists and creatives.

Children supported by the Virtual School remain on the roll of the existing school or setting they attend, with the Virtual School offering support or guidance, including creative mentoring. The creative mentor role may come into play where statutory education and the national curriculum as traditionally delivered are not able to meet the needs of the vulnerable young person, and also where additional support for arts subjects – for example art and design, music, or design technology – is needed. Once a pupil is referred to the Virtual School, the arts coordinator spends time matching the pupil to a mentor, according to interests and availability. The Virtual School supports the creative mentor role by facilitating network events, training days, online courses and supervision support, and ensures that safety, safeguarding and all relevant checks are in place.

The creative mentor works collaboratively with the team of professionals around the child. This includes schools and other settings, social workers, education support officers, multi-agency teams, health care professionals where appropriate, foster carers and staff and managers of children’s homes. The support begins with the child–mentor relationship, where interests and ideas are shared and developed.

The creative mentor adopts a social pedagogical approach – a holistic, relationship-centred way of working across care and education. The shared or ‘social’ responsibility of supporting an individual, as in ‘social’ pedagogy, is fully embraced by the creative mentoring role. Mentors work collaboratively with the young person and other professionals and carers; together they explore the most appropriate and engaging ways to develop new skills and draw out the young person’s potential.

Creative mentors work with their young people in a variety of settings; at school, at home, in an artist’s studio (Figure 3) or in cultural venues such as theatres, galleries and workshops. Community settings and participation in community projects and events are all resources and places of learning to be accessed. On occasion trips and visits become an informal part of the ‘creative curriculum’. For example an interest or conversation around theatre production, lighting or sound may lead to a visit and a tour of a theatre and backstage, supported and facilitated by the mentor. This ‘social’ approach to exploring the young person’s interest, especially within the community in which they live, embeds a greater feeling of belonging through involvement and participation. It helps to develop identity, self-esteem and their place in the world. This is useful in particular for our unaccompanied asylum-seeking children and young people. Confidence to explore their surroundings and learn how to feel safe in their community is modelled and supported by the mentor.

As with social pedagogues, the creative mentors’ work looks to the many ways in which an individual can express or explore their interests in order to grow and learn. My own creative mentor work and work as an artist-in-residence at a children’s nursery is influenced by Loris Malaguzzi, an educationalist active in the 1950s, who set up the preschools of Reggio Emilia in northern Italy. Malaguzzi (1950) described the ‘100 languages of children’, acknowledging the many ways in which children can express themselves or discover their potential as human beings. Introducing a variety of easy-to-access art materials, creative resources or opportunities opens up a new world for them to explore. Yet impoverished creative provision in schools is all too common, and limits how we explore the world around us. Through modelling a creative practice to our children, young people and those around us, we push the boundaries of what we know and understand. I marvel at the innate creativity demonstrated by very young children in the nursery school (aged three to five years). At such a young age they do not have the imposed boundaries of how and what we should draw and paint, of how many legs the ‘astronaut-snowman’ should have for example. They express themselves through imagination, through observation, mark-making, mess-making, tangling and smoothing. Their drawings contain emotion, pattern, colour and sound. A child who has not yet mastered drawing with a pencil might paint with three brushes in one hand, or paint over the lines of the colouring page or beyond the edges of the paper (Figure 4). I try hard to encourage schools, other education settings and children’s homes to buy high-quality brushes, paints and pencils and set up a place where getting messy and painting or using clay is OK. Making the most of the resources of our body too, such as through dance, music and sport, is of course also important. Expressing ourselves and discovering our potential as human beings empowers us and makes us feel good: through creative mentoring we can help our young people to achieve that too. As artists and creative mentors we share our skills and experiences, and encourage new ways of expression and new possibilities.

Many of the young people we work with are not in full-time education, employment or training. Often our young people have experienced mental health difficulties as a result of early trauma. Our work through the Virtual School helps to move young people towards a place where more formal education or training might be possible. Development of creativity can enhance interventions in a broad and holistic way well beyond the sessions. This occurs, for example, where family members, carers or social workers become involved in the young person’s creative projects, or at events, where shared experiences have strengthened relationships, trust and confidence. Many of our young people have subsequently enrolled onto creative courses, explored jobs in the creative industries and taken up hobbies and pastimes in the arts. Sometimes the work extends an already established interest of the young person’s, or may help them to find a new way to engage and participate.

Breaking the ice: The beginning of creative work with a young person

Developing relationships is key to being able to begin creative work that is useful to the young person. Authentic connection and engagement with the young person can be nerve-wracking for both the young person and the creative mentor. As a creative mentor working with a young person I sometimes get the feeling that I am being tested. I jump through hoops and balance on tightropes: some to be expected, some not. But I’ll do whatever it takes to pass the test and become accepted. This occasionally extends even to the extent of feeling embarrassed or humiliated, where introducing myself as an artist and offering a new experience is challenged or looked on suspiciously.

These are experiences shared by many of my colleagues. We recognise that for a young person who may have suffered early trauma, the prospect of developing trusting relationships can be a non-starter, fuelled with anxiety and sometimes fear. However, it is the concept of trust that pops up again and again as the only way to help a young person recalibrate their anxieties around relationships, to build a future and relationships that feel safe. The creative mentor relationship offers a way forward, to experience things differently: a means of self-expression through the arts.

Engagement with a creative mentor might represent the first time the young person has been able to exercise autonomy, make choices and develop trust, and it may feel precarious. In the beginning, connecting with or attuning to the child or young person we work with is key to the creative mentor process, and as suggested is not always easy. It can feel risky exposing our own feelings of uncertainty. However, I usually find that being myself, letting my guard down, and showing the young person some of my own vulnerabilities can begin the process of connecting and attuning.

In his enhanced review of creative mentoring with children in care, Dr Paul Kelly (2016), a specialist senior educational psychologist, looked at the significant attributes of the creative mentor role for the county council’s Virtual School. Being ‘emotionally attuned to the young person’ is listed among the top three essential attributes, and is definitely one that I identify with. This attribute contributes to making us effective practitioners but has a flip side too. Empathic or emotional attunement to the child or young person we work with can on occasions lead to vicarious trauma, where we might soak up, relate or attune to the young person’s past or present trauma. This can become so overwhelming that we can begin to experience and feel the physical and emotional consequences of it ourselves. We can begin to feel how the young person feels. For this reason peer support and supervision from trained professionals is an essential part of our work, to reflect on our own feelings. Emotional attunement is part of our implicit practice; it is something we do naturally in order to begin work and develop relationships with our young people. Taking care of ourselves and reflecting on how our personal, professional and private life contributes to our practice as a creative mentor is important, and is a key aspect of practice shared with social pedagogues. The helpful concept of the three Ps – professional, personal and private – in social pedagogy, developed by Jappe (2010), is described in detail on the ThemPra website, http://www.thempra.org.uk/. This concept encourages us to hold in mind the parts of our lives, or details of our lives, that may or may not be useful in our work with young people. Keeping a professional focus is essential in decision making, especially around safeguarding issues and keeping the young person safe. It may be that sharing a personal experience with our young people could help them consider possibilities and how things can be different, or show them that what they are experiencing is normal (for example, recounting my own memories of stage fright before a performance when I was the same age as them). Private aspects of ourselves may need to be kept that way so that we ourselves feel safe. Authentic engagement and trusting relationships work both ways, and in considering the three Ps ourselves we may be able to recognise the difficulties our young people might have when discussing private or personal issues. A glimpse of our personal or private life may just help that authentic connection to be made.

The creative experience

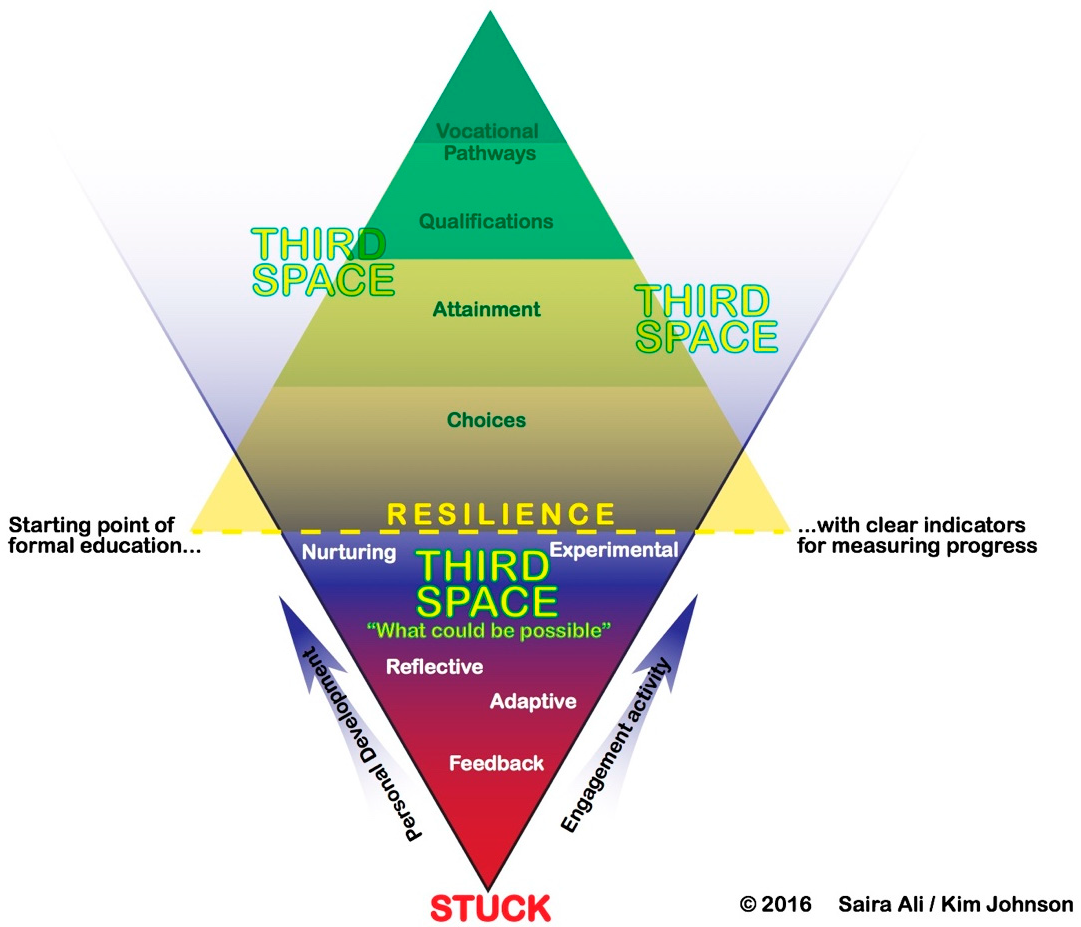

As creative professionals we have additional resources to draw on in our practice, bringing alternative means of communicating and interacting when needed. We can offer activities that are both absorbing and therapeutic, and present practical and sensory activities when words and conversation do not flow easy. Clay work, felting, painting, designing and making music offer ways forward. These activities have the capacity to connect to the inner world of an individual through the process of making and creating. Opportunities to imagine and make-believe come into play when working creatively, and may be new and exciting to the young person. It is here, during these sessions where work or play can begin, that creativity and the imagination can be discovered, and a way back into education or training can be nurtured and encouraged. Johnson and Ali (2016) of DCC’s Virtual School designed a model to illustrate this emergent ‘creative’ third space where change occurs with our young people (see Figure 5). It is in such a space, similar to that described by Winnicott in his book Playing and Reality (1971, pp. 55, 72) as a ‘potential space’ or a place to play, where our creative mentor work takes place. Creative activity provides the mechanism or method through which change and growth can begin to emerge. The creative activity is described in social pedagogical terms as occurring through the ‘common third’ (Lihme, 1988), concerning positive shared experiences, where the focus is on the activity or task and not directly on the individual. The third space described by Johnson and Ali is the place where these possibilities and experiences are explored and reflected upon, and where the common third is exercised. The third space illustrates where the young person moves on from being stuck, towards personal development through purposeful engagement.

For most individuals, power and autonomy are at the heart of a struggle that is recognised as a rite of passage during the teenage years. Confidence as a young adult is built on a foundation of support and on the presence of role models, with trusted adults in the background, whether they be teachers, parents, grandparents or other family members. It might be useful then to consider that young people whose early childhood has been difficult or traumatic may have a distorted sense of self-worth, identity and autonomy. Overt sensitivities and anxieties concerning power and authority, learnt in early childhood, may have had a negative impact on confidence and self-esteem. The fundamental human right for children to feel safe may not have been supplied, leaving children and young persons to experience hypervigilance, mistrust and fear. In recognising these difficulties in early childhood we might begin to understand some of the behaviours we see, and adapt our activities and expectations accordingly. An awareness of some of these boundary issues and tensions that the young people may feel when our work begins can help to inform what and how we plan, in terms of the creative activities we bring to a session. For example, during a first session, a pre-planned joint activity such as clay-work, drawing or painting might be better than asking the young person to choose what they want to do. Making choices and being autonomous comes with confidence. An activity that can be done together will give the young person the opportunity to observe the mentor in a low-stress situation and feel supported. Could the young person’s key worker be involved and join in too? Maybe something that requires no guidance or instruction at all, such as a colouring page with beautiful designs or patterns, will do the job to break the ice.

I have worked with young people who appear to be in a constant struggle for control, fighting against everything that is organised for them in an attempt to gain some sense of self and power. Various tutors, colleges, schools and trips are provided and rejected. School refusal for these children and young people might not mean ‘I can’t be bothered’ but may be communicating ‘I’m scared’ or ‘I don’t understand these rules’; ‘I feel different to everyone else’ or ‘I don’t feel safe’. I was asked to join a team to support a young person who wasn’t attending school, and tried a number of approaches with short friendly visits, popping in to say ‘hi’, and then longer visits where I set out a stall with all my wares – felt-making, clay-work, drawing, painting, jewellery-making – as well as offers to walk out on the hills with my dog or take a trip to the theatre. I was like a magician, performing all the best bits of my show in one go, but with this young person I soon ran out of tricks. Finding a way to connect or attune can often be tricky. I have on occasion during my work been subject to rants, and told that my stuff is for babies and that they aren’t going to do any ‘arty s***t’. It may be that nothing we can do will be acceptable when things feel really bad. With this young person, I didn’t give up, I didn’t take it personally: I persevered. Motivated by the desire to give this young person the opportunity to develop creative skills, that might just give them the tools they need to change their default position, I returned on the next session to offer my support and explain that the session time was there for them, if and when they needed it. The young person may have been surprised to find that it wasn’t so easy to put me off. They perhaps learnt that I was accepting them for who they were, without judgement; that I was willing to return, keen to keep trying. In psychotherapeutic terms I treated the young person with unconditional positive regard (Rogers, 1951) an approach that universally nurtures wellbeing and trust.

These experiences remind me of work by Dan Hughes (2016), a clinical psychologist who specialises in working with children who have suffered early trauma. He describes the essential experience of ‘surprise’, whereby defensiveness can be reversed through an unexpected turn of events, presenting the young person with a good feeling and an increased dopamine hit. Hughes promotes the use of PACE (Playfulness, Acceptance, Curiosity and Empathy) to create these opportunities as often as possible, and so reduce defensiveness and promote engagement through repeated positive experiences. This perhaps serves to disrupt what was before a predictable trajectory of behaviour, making a small but decisive change.

I was invited, despite the challenges we had encountered, to continue to work with the young person discussed above. The next few weeks were still tricky, but in spite of the difficulties that the young person was clearly experiencing in other aspects of their life I was able to remain a positive presence. It can often be difficult to see the benefits of our role when the young person’s experience is clouded in anger or anxiety, from an issue or worry outside of our control or understanding. Getting some clarity from staff after a difficult session or checking in on them before a session can help to give us a better picture of what the young person is dealing with. Medical appointments, family visits, medication issues or a night without sleep can make or break a session. Factoring in sessions that will be cut short or that prove to be non-starters has to be part of the work. I found that key staff members can also really make a difference to how the young person engages, getting alongside them, encouraging and cajoling. Working as a team with others supporting a young person is critical in making all of our work with vulnerable children and young people more effective, responsive and authentic. Such teamwork might involve watching how various strategies work one day but not the next, and identifying how one particular staff member might seem to have the ‘magic’. A number of my sessions would not have happened if the staff member had not agreed to participate. The balance of power can shift when an activity is led by the young person, or when a staff member joins in and becomes a participant. Power dynamics within sessions are as important as the activity itself, either promoting or inhibiting participation.

Being alert to all these variables and having the flexibility to adapt the activity accordingly goes a long way. One young woman with whom I worked created an incredible series of beautifully painted canvases that were eventually exhibited locally. The paintings began as an opportunity for her to show me her skills at blending and contouring using makeup brushes – a specialist technique used by makeup artists. If her carer hadn’t given me a tip-off about her interests and talents, the opportunity might never have arisen. Teamwork and collaboration add value to the experiences for the young person, building confidence in what they are good at, developing their interests and ultimately building intrinsic motivation.

Creative activity as the focus

Working together with the young person and using an activity as a way to share positive experiences promotes trust. The focus of attention is directed at the image, craft or artwork rather than at the individual. Working together can also help to level or neutralise the power relationship between the mentor and young person. It might be that the young person can lead a session and demonstrate a skill that he or she has. As an example, one young person with whom I worked turned out to be great at making origami flowers (paper folding – see Figure 6), which happens to be something that I, the mentor, was hopeless at. Using this activity was a great opportunity for her to feel confident and competent.

This is an illustration of how our work as creative mentors has parallels in practice with social pedagogy concepts and frameworks, encouraging us as creative mentors to look at the ‘what’ as well as the ‘why’ in our work, recognising how the very essence of our practice – ‘the common third’ (Lihme, 1988) or the creative activity – helps to establish the essential and enabling trusting relationship. When the focus becomes the task, and the relationship grows through those positive shared experiences, the creative activity becomes the mediator – an alternative means of communicating. Working in this way takes the emphasis off the child. Instead the adult and child engage together, jointly, in the activity. A safe space is created wherein play can begin and conversations flow more easily. The child can think and explore possibilities through creative and artistic activities.

There are a number of methods through which to deliver a creative session with a young person. These can include working independently or collaboratively, or using each other’s work to copy from or as an inspiration. Sian Stott (2018) has described the purposeful use of copying as a method to develop attunement between client and practitioner, in ways both interesting and relevant to our work. She has suggested that collaborative art making with patients or clients may lead to explicit attunement, where a shared understanding is visible and directly acknowledged, and can be used as an opportunity for further discussion and progression in the therapeutic alliance.

Managing difficult sessions

It is exciting and uplifting when sessions appear to support and empower the young person, when magic moments bring a new idea and a sense of optimism or hope. New skills learnt may have enabled them to design and build a racetrack for their favourite matchbox cars, or a piece of art may bring a smile of pride and sense of achievement. But how do we move forward after or during difficult sessions? A session may leave us feeling deskilled and exhausted, making us wonder what we did wrong or what we should have done differently.

Staying ‘with’ the relationship and giving it primacy over behaviour is easier said than done, but finding a way to exercise unconditional positive regard even in the most difficult of circumstances will have a lasting impact on the young person. Sometimes our own feelings of self-worth can get in the way of what is right for the young person. Mostly I would say perseverance and resilience are key attributes for us to draw on when working with troubled young people, but occasionally persistence in the face of resistance may not be the key. Reflecting on our practice and on the three Ps (Jappe, 2010), as well as gaining the support of other professionals, is essential in helping guide decisions on how to proceed.

Holding or containing difficult feelings and working hard to figure out who the feelings belong to can be a powerful experience. Experiencing uncertainty in a ‘safe’ space changes what might otherwise be a predictable outcome. It plays with an alternate way of being for the young person, or even offers new possibilities. I can in particular draw on a time working with a young person who often felt she was in a hopeless situation; she described her despair as a ‘whirlpool pulling her down’. On one occasion she didn’t want to talk, but was clearly being pulled into that whirlpool. The creative resources became the focus of the session; they were the ‘common third’ (Lihme, 1988). The felting fibres provided a way to continue the session, and for the young person to communicate something of what she was feeling. Words don’t always do the job. I set out my felting wool fibres in front of her, a beautiful spectrum of fringed, feathery, cloudlike colours: a delight to the eye, an opportunity for a shift in sensory perceptions. I offered her a selection of soft merino wool fibres to lay out on the table, to smooth and stroke. Together we began to create whirlpools out of those coloured fibres. She asked me to help as she laid black on purple and blue on black. After a period of hesitation I tentatively offered her some slightly brighter (more hopeful) colours. Together we felted the colours with soap and water, with soothing, circular motions. We didn’t talk much, just worked side by side making something really beautiful, perhaps transforming. Maybe this visual process of change helped shift the feeling of hopelessness. Connecting inner feelings with a process that is tangible and real can help make sense of the feeling. This is especially so when the feeling is represented in a form that can be experienced through all the senses, through smell and touch and as a visual piece of art.

Maintaining a safe and sustainable practice

I have watched a young person’s whole demeanour change during a creative activity. It is sometimes clear to see that working creatively is a therapeutic experience that promotes wellbeing, and can be that safe space where difficult issues can emerge and transform (Figure 7). When considering the therapeutic benefits of our role we must consider the bigger picture of creative support, and be aware of where the limits of our expertise lie. Discussions may be necessary to keep a young person safe. Further referrals may be needed to address a deeper issue around mental health and attachment difficulties. The creative mentor role is not the role of therapist.

However, it would not, in my view, be ethical to ignore or overlook difficult feelings that emerge during our sessions, when working with children who have suffered so much. There are times when we find ourselves having to make a choice about how we handle sadness, difficulty and despair within a session. How we handle it often depends on how strong or grounded we ourselves feel on that particular day. It therefore feels right to draw attention to art therapist and psychologist Arthur Robbins, who described ‘holding’ and ‘containing’ difficult moments as an alternative to distracting or diverting attention away from them.

Robbins (2001, p. 64) in his chapter ‘Object Relations and Art Therapy’, wrote ‘again I cannot emphasise too strongly that growth occurs from the process of going through the pain of an unmet stage of development… to rob a patient of his anger, pain, and despair, no matter how well intentioned, is to do a disservice.’

When such feelings arise it is important to be mindful of how to end a session, bringing the young person back into a safe place both physically and emotionally, and ensure that carers and staff are aware of difficult sessions so they can continue to support the individual after the time together is finished for the day. If challenging and difficult feelings rise up in a session and are held and contained appropriately the young person will benefit from feeling understood and supported. Peter Fonagy (2020) in a recent BBC Radio 4 interview, on the programme The Life Scientific, described the process of ‘mentalisation’ so eloquently, as the need to be understood. To mentalise and share our thinking with someone who is actively listening and authentically engaged enables us to better understand our own thoughts and feelings. Fonagy believes that such a process is the cornerstone of good mental health, and advocates mentalisation throughout care and education and in our daily lives. Creative engagement offers a whole range of ways to engage and communicate in this way.

How do other professionals view the creative mentor role?

A joint understanding of the process and impact of creative mentoring is one that as a workforce we continue to articulate, explore and share. A social pedagogical approach, one that is both holistic and person-centred, is at the heart of creative mentoring, where play-based, purposeful, creative activity motivates positive engagement. In a personal communication, Paul Kelly, the Virtual School’s lead educational psychologist, describes how ‘Creative mentoring is an opportunity to put education right at the centre of young people’s worlds through a social pedagogical approach to learning in the widest sense’.

There is some uncertainty in regard to how others perceive the creative mentor role. This may also have an impact upon its effectiveness, and in some cases may be the cause of difficulties in getting started. As artists, creative mentors are good at working with uncertainty and being brave, to see what emerges, often beginning work without a specific aim or objective other than a desire to develop a relationship, get creative and explore possibilities with the young person. The mainstream education system on the other hand is based on structure and a standardised curriculum. Here we see an opportunity to work in a different way: to facilitate a complimentary service, to find a way for our young people back into education through creativity, to reengage. It is clear that practice methods and techniques vary and are often exclusive to the mentor delivering them, while the settings in which mentoring sessions take place are varied (Figure 8). The various creative backgrounds, too, as well as the range of creative mediums used by mentors, provide opportunities for a truly unique and personalised curriculum. Part of our work includes capturing or documenting significant moments and notable progress with the young people we work with in. Progress is tracked on a number of measures, including wellbeing, confidence and problem solving. These outcomes and evaluations help us to communicate the impact and benefits of our service to the teams around the children with whom we work, including in education planning and review meetings with other professionals. Carers, staff and social workers are invited to share in progress and achievements during our creative projects.

The lasting impact of our work

Motivation to do the work we do comes from a number of places. During a piece of research to support our professional development, I expanded on aspects in Kelly (2016) to explore a little of where our motivation as creative mentors comes from, which in turn supports the young people we work with. Kelly’s reference to Wagner (2015) in his ‘Enhanced Review of Creative Mentoring with Children in Care’ described how intrinsic as opposed to extrinsic motivation is vital. He went on to say in his report that ‘by re-igniting this sense of play, interest and passion, a new possibility of purpose and an intrinsic motivation can be fostered through the involvement of a creative mentor’.

Creative mentor Joe Doldon described how his motivation is driven by a feeling of ‘nourishment’ that comes from a good session, ‘when both of us (the young person and I) come away from a session feeling good’. It is perhaps the hope that we can take from our work that keeps us fuelled. Creative mentor Wendy Johnson said, ‘I know what it’s like when she’s at her best, I’ve seen it, getting a glimmer gives hope and optimism to our work’. Creative mentor Dan Marsh, like Wendy, also talked of the subtle changes that one might see during sessions and over time that give hope and grounds for optimism, which can sometimes be lost or overlooked in the search for bigger outcomes and progress. Subtle changes include those in body language: a more upright posture, less fidgeting, less swearing and becoming more absorbed or focussed. Dan described the need to adapt and change activity quickly to enable engagement, support positive work and prevent the breakdown of both the session and the relationship. It was clear from talking to Dan and other mentors that trying hard to avoid a breakdown can sometimes be a minute-to-minute exercise, often an exhausting one, wherein a number of techniques, methods and tricks up your sleeve come into play. Having a range of creative tools – from music, drama and dance to woodwork, drawing, painting, felt-making (Figure 9) and clay – makes up a service like no other. Each mentor has their own influences and motivating factors that are intrinsic to them as individuals and underpin their practice. Nathan Geering, a creative mentor and dance and performance artist, described how his love of rap and hip hop helps him attune and connect with the young people he works with:

its origins lie in the ghetto neighbourhoods of the Bronx in the US, a musical genre and culture formed in the 1970s. Minority groups of young people growing up in poverty and discrimination created this art form to give them a voice, to make them visible. The ethos and energy by which the genre was created resonates with the young people that I work with.

Hope, it seems, grounds what we do as creative mentors, alongside the intrinsic creative forces that motivate our practice. Hope that we are making a difference provides nourishment and motivation to our practice. Those who have worked closely with children will at some point wonder whether their work has had a lasting impact on those children’s lives. Fairly recently I bumped into a young man now in his early twenties who I worked with when he was 10, some 12 years ago. I had worked with him as a resident artist in his primary school, providing one-to-one creative support for one afternoon each week throughout a whole school year. We worked creatively together with Lego, drawing, model-making and painting. The school had struggled to cope with him. Sadly he was in the end permanently excluded from his primary school, but thankfully with personalised support and opportunities to learn and play instruments he turned his life around through music. In our conversation on a 20-minute bus journey he remembered looking forward to our creative sessions together as a time ‘to do what he wanted to do’. He recalled that the art sessions offered a breathing space for him, and reflected on them as ‘a time where he felt calm’. Not all of us get the opportunity to have that feedback; all we can do is hope, and listen to the testimonies of others who may be echoing the experiences of some of our own young people.

For more information about Derbyshire County Council’s creative mentoring service for looked-after children and young people, see https://www.local.gov.uk/derbyshire-county-council-using-creative-mentoring-support-looked-after-children.

Author biography

Claire Parker has worked as a creative mentor for Derbyshire County Council (DCC)’s Virtual School since 2014. Claire is a (HCPC) registered art psychotherapist, having completed her Masters in art psychotherapy in 2014. She has worked in a Manchester primary school for ‘Place2Be’ (a national children’s mental health charity), and for East Cheshire Hospice. Claire runs workshops for schools in the High Peak, Derbyshire, and has been Hadfield Nursery School’s resident artist for over a decade. Her degree studies in working with children in the early years ignited a special interest in trauma, loss and attachment in the early years that can impact later development. This has informed her work and commitment with older teenagers as a creative mentor for DCC’s Virtual School.

Her early career as a scenic artist and prop-maker for television and theatre brings experience and expertise in the arts to her current role as creative mentor.

Claire believes that the creative process supports communication, social and emotional issues and builds resilience, confidence and self-esteem, helping young people achieve their potential.

Declarations and conflict of interests

The author declares no conflicts of interest with this work. All participants provided informed publication consent and declaration forms are freely made available to the Editors upon request.

References

Fonagy, P.. (2020). The Life Scientific: Peter Fonagy on a revolution in mental health care. BBC Sounds. January 28 2020 Retrieved from https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000dpj2 .

Hughes, D.. (2016). After attachments cause pain: The pathway to discovering comfort and joy. Conference April 2016 – Frightened to love: Working with attachment issues and traumatic loss in children, teenagers and adults. London: The Centre for Child Mental Health, Britannia Row.

Jappe, E.. (2010). De 3 P’er. Blog. Retrieved from http://10rs1gruppe6.blogspot.com/2010/09/de-3-per.html .

Johnson, K.; Ali, S.. (2016). Creative mentoring, the illustrated ‘third space’. Matlock: Derbyshire County Council’s Virtual School.

Kelly, P.. (2016). Creative mentoring with children in care: An enhanced review. Matlock: Derbyshire County Council.

Lihme, B.. (1988). Socialpædagogikken for børn og unge. Et debatoplæg med særlig henblik på døgninstitutionen. Holte: Scopol.

Malaguzzi, L.. (1950). 100 languages: No Way. The Hundred Is There. Reggio Emilia Approach. Retrieved from https://www.reggiochildren.it/en/reggio-emilia-approach/100-linguaggi-en/ .

Robbins, A.. (2001). Object relations and art therapy. Approaches to Art Therapy. 2nd ed. Rubin, J. (ed.), London: Routledge.

Rogers, C. R.. (1951). Client-centered therapy: Its current practice, implications and theory. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Stott, S.. (2018). Copying and attunement: The search for creativity in a secure setting. International Journal of Art Therapy 23 (1–2) : 45–51, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1415364

Wagner, T.. (2015). Creating innovators: The making of young people who will change the world. New York: Scribner.

Winnicott, D. W.. (1971). Playing and reality. London and New York: Routledge Classics.