Introduction

In this article we problematize the turn to action research as an explicit strategy towards ‘improvement’ within the climate of performativity that has dominated schools in the UK and abroad for three decades. Demands for the continuous improvement of student outcomes have created pressures for teachers in seeking the most effective ways to develop their practice. At the same time, this high-stakes environment can increase reliance on what appears to be ‘working’ and makes risk-taking less attractive. There is significant challenge in choosing the right tools to ask questions about practice that may be disruptive of the existing orthodoxies and routines that shape how learners experience school. The article is written by four teacher educators who have experience of working within the primary, secondary and post-compulsory sectors to develop and support inquiry-based projects in England and Wales. We examine action research from the perspective of the impacts of neo-liberalism (Ball, 2012), which have encouraged a competitive basis for educational development in the UK and globally. Such impacts include the standardization of pedagogy and curriculum in pursuit of target-driven goals for teachers and students, making them subject to accountability measures that impede notions of risk-taking and practice variation. The limitations of teachers’ ‘filtering mechanisms’ have been identified (Evans et al., 2017: 415), by which the schools and networks to which teachers belong can inhibit the development of questioning perspectives. These are the recent historical conditions that inevitably shape societal concepts of education and the politics in which action research is situated. Additionally, Thomson (2015: 309) reflected that, within these historical conditions, action research can be perceived as ‘slight’ and at ‘the bottom of the contemporary methodological hierarchy’. Large-scale longitudinal studies can take precedence over localized, context-specific research that brings about change in one person, group or institution. We discuss if and how teachers in a directed profession (Bottery and Wright, 2000) can be enabled to ask research questions that are worth asking and that address ‘equity-linked problems of practice’ (Grudnoff et al., 2018).

Kemmis (2006: 459) accused action research of lacking a ‘critical edge’ and falling short of its emancipatory origins and goals of generating ‘educational critique’. The danger is that action research performs an illusory role, appearing to offer teachers the opportunity to enact change, but in fact it acts as ‘a vehicle for domesticating students and teachers to conventional forms of schooling’ (ibid.). Lawton-Sticklor and Bodamer (2016: 396) suggested that although there is an extensive field that examines the history, theory and practice of teacher research, there is insufficient attention to ‘how inquiry stance is learned and developed’. In response to this, a process for developing critical dialogue by which to refine the focus of action research projects is proposed in this article, drawing on developmental work with teachers in different sector settings in England and Wales. An explicit focus on ‘changing the question’ in formulating action research is explored, offering the possibility of expanding critical perspectives that have socially just aims at their core.

Reclaiming action research from the neo-liberal agenda

McNiff (2002: n.p.) identified the ethical imperative for action research thus:

the need for justice and democracy, the right of all people to speak and be heard … of each individual to show how and why they have given extra attention to their learning in order to improve their work, the deep need to experience truth and beauty.

Uncompromising values drive this vision of action research, which promotes equity at the heart of a wider social project for education. This is one in which teachers are enabled to be agentive and in which schools become sites of social change. It places learner voices (both students’ and teachers’) at the centre of increasing inclusive experience of school, bringing personal enrichment as a consequence of engaging with showing how and why extra attention is given to learning. Truth is part of this social project – alongside beauty, it is deeply experiential – a consequence of participating in action research, realized by each individual in terms of what is made meaningful for them. It is essentially based on the desire of teachers to do good – ‘to make things better than they already are’ (Coghlan and Brannick, 2009: 17); by this, ‘any action based on that research has the potential to transform the work we do, the working conditions that we sweat under, and most importantly the people who we are’. The assumption is that such engagement is personally enriching and expansive of the individual as an ethical, social and intellectual being. It is transformational. Such transformational potential lies in the relationship between individual agency and its capacity to bring about wider societal change – to make things better. From this perspective, striving for justice and democracy inevitably challenges dominant policy agendas that promote uniform solutions to educational problems.

The relationship that many teachers have with research has become explicitly aligned with UK school improvement agendas in recent years (for example, Welsh Government, 2011, 2013; Coldwell et al., 2017). In many instances, action research has been appropriated by policymaking within the armoury of strategies that have emerged within the Global Education Reform Movement (Sahlberg, 2011). These support the ‘ever-increasing demand for knowledge creation’ (Philpott and Poultney, 2018: 56) that affects schools and their networks, linked to neo-liberal concerns to improve student performance in international league tables. In this environment, Hart et al. (2004: 264) identified how many teachers feel a need to seek a ‘helpful kind of simplification’ to enable them to meet the demands of increasingly complex classroom teaching and public expectations, by which the differences between students are readily labelled (for example as high/low ability) and failure to engage with school experience is perceived as a problem that is located within the young person. Deficit thinking (Pearl, 1997) about students is a consequence, and action research becomes a means to rectify it. Pearl (ibid.: 229–34) identified deficit thinking as an obstacle to be addressed in order to achieve genuinely ‘democratic education’ in which equal ‘encouragements’ for learners are promoted. Deficit thinking has become prevalent, however, in the appropriation of action research towards improving results as part of the neo-liberal agenda. One consequence is a diminished capacity to initiate critical inquiry that seeks to question the ways in which schooling frequently perpetuates unequal access to learning. In such a context, mutant forms of action research are used to promote the treatment of students who fail to thrive in such conditions, rather than ask questions that attempt to change the conditions themselves.

Kemmis (2006) identified the proliferation of ‘inadequate’ forms of action research that perpetuate dominant practices and, in effect, neutralize questioning of the status quo in schools. These aim to improve teaching techniques while not questioning the contexts in which existing techniques have become the norm. They seek to increase efficiency and not question the efficacy of practices, and they aim to implement policy directives without questioning the policy rationale and assumptions. He further argues that action research that is conducted without attention to learner voices and by sole researchers ignores the need for genuinely critical conversation with those who are most affected by what is happening. Such research is unlikely to bring about meaningful change in schooling as it is experienced by students, particularly those who do not present as ideal learners. Action research needs to make it possible to tell ‘unwelcome truths’ and to shape school environments that allow this to happen:

building and securing such conditions is an integral part of the obligation and the duty of the critical action researcher – it is our own small investment in making a worthwhile polis, a community that can conduct itself civilly through reason and care for the good of others. (ibid.: 461)

Action research is – or should be – a disruptive practice. This is essential for teachers who undertake research that is concerned with increasing social justice, resisting a drift towards goals that can be fixated upon student attainment. The position of teachers who want to ‘do good’ in this context is thus conflicted. Daly and Taylor (2020: 146) have argued that ‘there are ambiguous consequences for the role of research in developing critically informed professionals, capable of independent critique of “what works” in classrooms and for individual pupils within unique contexts’. The challenge of providing genuinely inclusive education in highly competitive performative contexts is a global one, recognized across vastly differing education systems (UNESCO, 2017). The conflation of increasing results with increasing the quality of life chances is a problem that was identified by the UNESCO (ibid.) report. In this climate, increasing results as rapidly as possible becomes a powerful proxy for reducing inequities in school systems.

In the judgemental conditions of contemporary systems, it is understandable that teachers who seek to ‘do good’ can be influenced by ready-made solutions and apply them to attempt to remedy the underperformance of some students. This is a long way from notions of practice that are based on expressing ethical, nuanced understandings of ‘a good life’ or ‘a good society’ that are highly complex (Carr and Kemmis, 2009). There is limited tolerance of the time it takes to go beyond surface tinkering that leaves intact the deep structures and practices that maintain unequal access to learning within schools. There is even less recognition of the need for deliberately disruptive professional dialogue that is focused on confronting long-held beliefs and customs. All members of school communities are implicated. Without an investment in time and cultural shift for action research to develop the school holistically, leaders can steer professional attention towards discovering ‘what works’.

There is a need to reclaim action research from the neo-liberal agenda. Forms of action research that are heavily influenced by government-directed improvement agendas are ‘likely to be and to produce conformity and compliance to authority rather than a critical evaluation, asking uncomfortable questions about the quality of education offered in a school or school system’ (Kemmis, 2006: 460). An example can be found in the recent history of curriculum reform in Wales. The School Effectiveness Framework (Welsh Assembly Government, 2008) emphasized the importance of action research within a professional learning community model, to support teacher learning related to a new school curriculum – ‘Curriculum 2008’. However, schools found limited opportunities to engage in related action research, and they struggled to sustain collaborative research cultures in accordance with the model for professional learning communities (PLCs) required by the government framework. Ten years on, the OECD (2018: 17) reported that many schools had an underdeveloped ‘culture of enquiry, innovation and exploration’. Conflicting policy agendas militated against the realization of PLCs that could be genuinely collaborative and challenging of existing practices. Opportunities for critique were in fact bounded by parallel increases in accountability, driven by international league tables. Most recently, however, the latest curriculum changes in Wales following the Donaldson (2015) review provide another opportunity to refocus action research in schools. This curriculum is designed to increase learners having a greater say in the what and how of their learning experiences, and schools and teachers are required to share in its construction. There is the possibility of new relations between teachers, schools and accountability regimes, reflecting how participants can become partners who are willing and able to learn from each other. The national inspection service in Wales has identified schools that are moving towards ‘a non-threatening and supportive culture’ (Estyn, 2018: 3) that enables teachers to engage in conversations around practice. Such change in teachers’ learning orientations can be hard to achieve (Pedder and Opfer, 2013), however, without sufficient attention to individual self-transformation and collective professional dialogue. Teachers need to unlearn much that has been taken for granted as effective, to build genuine, dialogic communities that are capable of critique and inquiry. It is too early to gauge the outcomes, but as far as the UK is concerned, this may be an opportunity to reassert the emancipatory dimensions of action research.

The struggle for truth and beauty

Action research occupies a position with conflicted expectations of teachers who strive to make things better than they are. Teachers in a directed profession can become complicit in ensuring minimal changes, collecting evidence of what is ‘working’, asking questions that seek reassurance and positioning students’ struggles to learn within deficit analyses of their ‘problems’ to be solved. In fact, ‘it could be argued that most school contexts provide a near-perfect storm for research inaction by teachers’ (Poultney, 2019: n.p.). Ultimately, action research can become an instrument for the ideological co-option of teachers. The concept of ideological co-option was developed in the field of critical language analysis to express the ways in which individuals become compliant with dominant belief systems (Fairclough, 1992). Their compliance is vital to perpetuating such systems and the inequalities they bring. Opposition to inequalities is neutralized by engaging those within the system in helping to maintain it. In schools, restricted forms of experimentation are authorized and effectively distract teachers from challenging questions that are not asked about taken-for-granted routines and behaviours that create inequalities. The relationship between the individual, the professional community and the wider societal context becomes a powerful means of ensuring that the questioning of dominant practices, and the belief systems on which they are based, is neutralized at each level.

For example, selecting students who are eligible for free school meals for an intervention has become a popular focus for action research, but can distract attention from the reality that the performance of these students is a high-stakes measure of the performance of the school. We have witnessed a staffroom where photographs of students who are eligible for free school meals are posted on the noticeboard with the call to action – ‘These need 5 Cs’ (Grade C indicated the threshold pass mark in national qualifications at age 16). Who would argue that their life chances would not be materially affected by obtaining these? What teacher would argue they should not be supported to attain them? The point is about what agenda is being served here. The teacher who is committed to reducing the impact of poverty on students’ life chances may be attracted to identifying groups of students who are economically disadvantaged, and to providing special attention to individuals. Their efforts, however, take place within a climate of high accountability that is outcomes driven. Students’ deficit economic status becomes the indicator that attention is needed to their learning. Identifying them for action by teachers deflects from the real questions that need to be asked about the accessibility of the curriculum and how all learners are valued. The quality of teaching is part of the discussion, from the viewpoint of the classroom as a community of learners together. A deficit construct of these students means that crucial questions are not asked about why the curriculum and prevalent pedagogies do not meet the needs of all learners. In constructing the students as objects of change, there is limited questioning of the organization of schooling, and the ways that students have very different (and unequal) experience of the curriculum and the social and intellectual affordances of classrooms. The questions that are asked need to change. How can students and teachers together create a fully integrated learning environment for all students? How can social integration be fostered through collaborative work in the classroom? Can group peer assessment enhance all students’ understanding? Such questions and many more offer alternative understandings of changes in action that involve learners and teachers in mutual development.

The neo-liberal appropriation of action research needs to be directly tackled. Without this, action research is aimed at reductive goals that have been described by Kemmis (2006: 469) as:

Problematizing the work of teachers, not the schools and systems they work in, and not the curricula, pedagogies and modes of assessment that operate across whole school systems to constrain teaching and learning within state-approved boundaries.

The need for collegial dialogue in action research

The need for teachers to experience rich, emancipatory inquiry is evident. Door (2014) emphasized the role of collaboration and dialogue in allowing new perspectives and creativity to emerge though regular opportunities for teachers to talk and learn to exercise ‘gentle scepticism’ regarding immediate solutions to questions. Soultana and Stamatina (2013) analysed the impact on teachers of shared planning, implementation and evaluation of classroom projects, developed through collaborative action research. They found that although collaborating, sharing and negotiating were seen to be important elements of professional learning, they were rarely actually practised by teachers. Similar conclusions were drawn by Pedder et al. (2005) about limited engagement with team teaching, joint research, and evaluation and peer observation. The conclusion drawn by Frost (2012: 208) is that ‘if collaborative enquiry-based activities are both effective and highly valued by teachers, what is needed is a strategy for enabling this to take place’.

Enabling elements of such a strategy are well-understood. Research is conclusive regarding the benefits of collaborative learning conditions within schools (Hipp et al., 2008), that can achieve reform (Harris et al., 2018), supported by school leadership (Kools and Stoll, 2016) and involving external partners (Cordingley, 2014). There is strong evidence that professionals outside school networks and accountability systems contribute significantly to teachers’ capacities to learn. Partners such as university teacher educators and external mentors (Daly and Milton, 2017) help to maintain the inquiring aspects of teaching by being able to introduce critical perspectives, bringing a ‘broader range of knowledge reflecting the wider research evidence than is available in any single school or staff room … which allows for the prevailing orthodoxies and “taken for granted” beliefs and assumptions within the school culture to be challenged’ (Cordingley, 2014: 25).

Given the support of leadership and involvement of external partners as core conditions, the effectiveness of professional learning communities relies greatly on the quality of dialogue that informs the research of teachers. Crucially, it is about ‘the extent to which the community understands and invests in protocols for how these dialogues will be conducted’ (Philpott and Poultney, 2018: 82). Philpott and Poultney (ibid.) distinguished between the disruptive affordances of ‘collegial’ and ‘congenial’ talk within professional communities. They identified severe limitations in ‘congenial’ conversations that are polite or superficial. They drew on Holmlund Nelson et al. (2010) to argue that ‘collegial dialogue’ is needed instead. It is collegial dialogue that can help to achieve disruptive thinking among action researchers. Collegial dialogue is based on ‘de-personalizing’ the core issues brought by teachers, focusing on growing intellectual curiosity about the wider, systemic contexts in which personal experiences and individual concerns are located. It moves towards an objective stance that helps to counter defensiveness in the ways in which teachers are able to interpret their experiences and perceptions of who or what needs to change. This is a prerequisite for making what is normally hidden ‘discussable’ – the deficit thinking about students that masks the inequities perpetuated where an inadequate curriculum, ready labelling and divisive groupings of students exist. It enables speculation about how things might be done differently. It requires structured support based on ‘being intentional about the nature of the dialogue in collaborative groupwork’ and using tools to ‘support a shift from congenial to collegial conversations’ (Holmlund Nelson et al., 2010: 178). These dynamics help to support what Kemmis (2006: 472) called ‘opening a communicative space’ (after Habermas) ‘in which emerging agreements and disagreements, understandings and decisions can be problematized and explored openly’. This is a fundamental necessity in action research. Kemmis (ibid.) went on to suggest that ‘emerging self-understandings’ must be tested – ‘negative and critical challenge’ is the point. ‘Cognitive conflict’ (Cobb et al., 1990; Holmlund Nelson et al., 2010) is essential to teachers’ transition from individual problems of practice to collective challenges of increasing social justice, and it is experienced through dialogic practices.

A dialogic framework

Based on our collective experiences, we propose a dialogic framework developed with teachers to support action research in schools, encouraging questioning and curiosity. The framework helps to challenge the assumptions that underpin prevalent research topics, reassessing the purposes of action research, of teaching and, ultimately, of education. We identify the inclusion issues that are raised by proposed action research questions that can focus on deficit constructs of students’ home backgrounds, gender, behaviour and ability – all viewed as problems to be ‘fixed’. Concerns that form the basis for initiating action research are reviewed through structured dialogue in specific stages. These stages build an exploration of the sources of the issues as they are perceived, and how they signal the inequities that are inherent in the organization of the school and the wider education system. Revised understanding of the issues and what they indicate lead to alternative possibilities for action that reflect the potential for teachers’ professional growth, creativity and risk-taking. This is a challenging process and it requires external partners to help make the systemic pressures that restrict teachers’ initial concerns ‘discussable’ (Cordingley, 2014).

The dialogic framework we propose has been developed using a ‘template-based’ approach (Rüschoff and Ritter, 2001: 226), capable of sustaining an intentional focus on social justice issues in beginning to formulate action research. The origins of such approaches lie in Ausubel (1968) whose work in cognitive theory on ‘advance organizers’ introduces learners to a framework that enables them to connect what is already known with more complex concepts. Advance organizers introduce a higher level of abstraction and wider significance than the immediate issues being discussed, bearing strong relation to the shift to ‘collegial talk’ among professionals. Rüschoff and Ritter (2001) argued that appropriate templates for dialogic tasks engage participants in the shared construction of new knowledge and act as cognitive tools. They are needed to support the deeply reflective thinking that is necessary for cognitive conflict to be generated between existing understandings of how things are, and reinterpretations of reality that lead to heightened awareness of the need for change, and dissatisfaction with the current state.

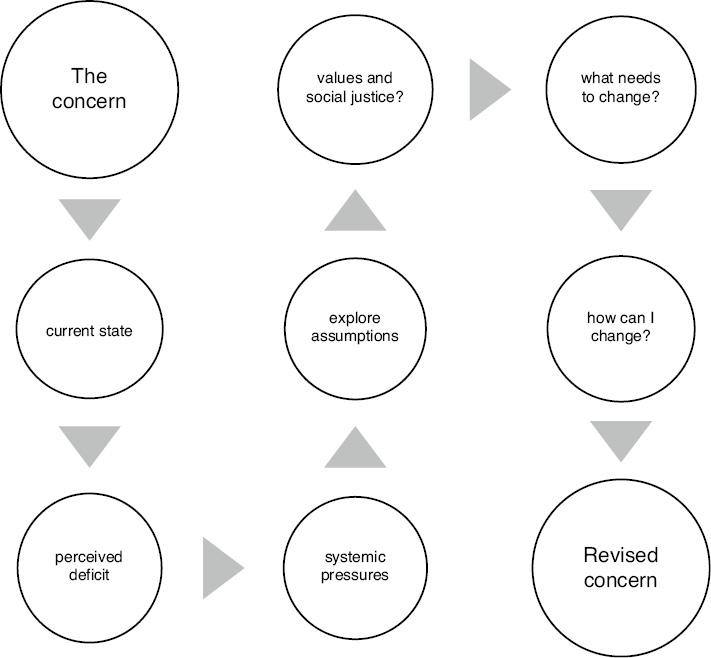

This is, of course, deeply, and necessarily, unsettling. The framework invites teachers to question the routinized practices (such as ‘ability’ grouping, fixed curriculum arrangements and the targeting of students who are eligible for free school meals for interventions) that may be assumed in the concerns they have to make things better. In learning triads, supported by external professionals in a ‘surgery’ role, teachers share the experiences, concerns and priorities that occupy them and that might be a focus of change through action research. The overview of the framework (see Figure 1) develops nine stages in a dialogic process around the concerns frequently articulated by teachers when invited to discuss their priorities for change. The framework is not intended to be prescriptive, and it has taken different forms in varied contexts. Such protocols are constantly evolving, being redesigned in response to local and individual contexts. This one has been modified over time, based on working as external university partners with over a thousand teachers in England and Wales on accredited and non-accredited programmes of professional learning over ten years, during a period of intense growth in teacher research linked to policymaking aimed at school improvement and related professional learning for teachers. It has been developed through our work with teachers on programmes including the Master’s in Teaching and Learning (2010–14), Master’s in Educational Practice (2012–18) and action research workshops with schools and via the Cardiff Festival of Education (2018) and an ESRC Impact Acceleration project (2019–20). These were opportunities to initiate action research with teachers in a variety of contexts, all of them based on collaborative approaches to peer-reviewing a ‘concern’ as a starting point, frequently in the form of a vignette or structured account of a critical incident (Tripp, 1993) provided by the teacher.

A series of cues expands the discourse, including: invitations to articulate experiences, issues and concerns; questions to identify the wider ‘regulatory climate’ (Brown et al., 2015); pointers towards identifying present and future inequities; and prompts for reflection that consider both individual capacity for change and the possibility of collaborative and wider institutional shift (see Table 1). Participants are encouraged to ‘go meta’ (Hutchings and Shulman, 1999) about the systemic pressures on teachers, leaders and schools that maintain deficit thinking about students and teachers who need to ‘improve’. Explicit questions of social justice become a focus based on ‘how things are’ and ‘how they might be otherwise’. The framework aims to support the active exploration of inconsistencies between teachers’ values and commitments to ‘do good’, and the unquestioned practices they carry out or are contemplating within schools. This is what Pedder and Opfer (2013) have called values–practice ‘dissonance’. Consciousness-raising is the aim of such a discussion protocol, deliberately seeking to align teachers’ moral and professional purpose with desirable change as a goal of action research. Pedder and Opfer (ibid.) identified the need to deliberately focus on increasing the capacity to learn among teachers and to build collaborative exchange. They argued that ‘becoming aware of inconsistencies between values and practices may motivate teachers to learn’ (ibid.: 544). Self-doubt can be productive (Wheatley, 2002) when it is explored within a purposeful dialogic framework, where action research can increase motivation for change. Ultimately, teachers are asked to articulate a revised understanding of their initial concern through the lens of social justice – ‘What is this issue really about?’

The dialogic framework – cues and prompts

| Stages | Cues/prompts | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | The concern | Articulation of teacher’s perspective on the concern that matters to them. Initial responses. Use of vignette, teacher narrative. |

| 2. | Current state | Exploration of feelings and beliefs that underpin the concern. Acknowledgement of the teacher’s positionality in the concern, of their responsibility. Acceptance of emotional dimensions. Initial thoughts on how things could be different – desired state for students and teacher. Recognition of the power of seductive solutions. |

| 3. | Perceived deficit | What would be the students’ stories of this concern? Examination of perceived responsibilities for the concern. Who is finding things difficult? What values underpin the concern? Who can learn here? What do they already know? |

| 4. | Systemic pressures | What are the pressures on the students? What are the pressures on the teacher? What are the pressures on the school? Where do the pressures come from? |

| 5. | Explore assumptions | What things are always done? Why? What is being ‘taken for granted’? What needs to be questioned? Who or what should change? How do students feel about these things? |

| 6. | Values and social justice | What inequalities are present in this concern? How can these inequalities be reduced? What is the risk of increasing inequalities? How are students positioned in this dialogue? What do I really need to change? What must I avoid doing? |

| 7. | What needs to change? | Is there anything I should stop doing? What systemic things need to change? The curriculum? The social organization of the classroom? How learning is assessed? |

| 8. | How can I change? | What agency do I have as a teacher? How can I really listen to students? How can I avoid surface changes? Who do I need to work with to achieve change? |

| 9. | Revised concern for action research | What is this really about? |

The framework is based on the concept identified in neuroscience of an ‘incubation period’ (Sio and Ormerod, 2009; Ritter and Dijksterhuis, 2014), which was applied by Lawton-Sticklor and Bodamer (2016) to teacher research contexts. It is a crucial phase in influencing the teacher’s learning orientation, helping to shape the meaning of the current state of things and of desired change. The incubation period is not directed towards task-fulfilment but is ‘associated with active engagement and processing’ (Lawton-Sticklor and Bodamer, 2016: 396). Although there is relatively little research into how the incubation period brings about changes in teacher perceptions, the emphasis on active processing is seen to be important. Ritter and Dijksterhuis (2014: 7) identified two central features of the incubation period, one being the avoidance of thinking that is ‘fixated’ on solving a problem, and the other the importance of ‘facilitating cues’. The framework reflects both of these features. Both are argued to help generate creative responses to initial concerns or perceived problems to be addressed, and the development of deeper awareness of issues that have a bearing on them. Most importantly, Lawton-Sticklor and Bodamer (2016: 396) emphasized the importance of ‘engaging complexity’ during this early stage of an action research cycle. It reflects the need to experiment ‘seriously’, ‘cooperatively’ and ‘doggedly’ (Stenhouse, 1975, 1980).

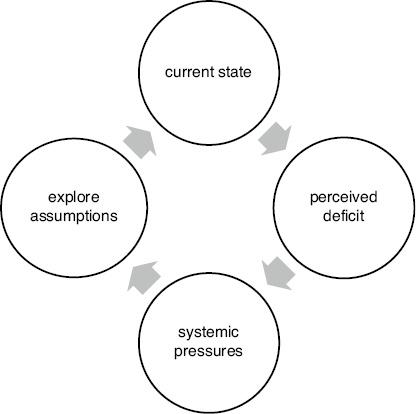

Teachers may spend varying amounts of time engaging with such an incubation period, extending over several conversations. It is this use of time that is sometimes reduced in climates where action research becomes a solution-focused strategy rather than a way of learning. Some stages warrant further engagement, and internal dialogue cycles can be needed (see Figure 2). Internal cycles can extend the focus on articulating and understanding awareness of the current state of things, as thinking is revised. Thus, the stages of dialogue exploring ‘current state’ – ‘perceived deficit’ – ‘systemic pressures’ – ‘explore assumptions’ may result in a return to a revised ‘current state’ to begin a further cycle. These early stages are important to invest in, as they depersonalize the issues brought by teachers, focusing on growing intellectual curiosity about the wider, systemic contexts in which personal experiences and individual concerns are located. They move towards an objective stance that is necessary to avoid defensiveness, before considering the issues of values and social justice that underpin the current state and possible change. They also help to prevent the fixation on problem solving in ineffective dialogue identified by Ritter and Dijksterhuis (2014).

Stages 6–8 begin an explicit examination of the social justice dimensions and initiate tentative consideration of ‘what needs to change?’ (stage 7). The aim is to move to these stages once a reasonably objective position has been achieved for the action researcher. The researcher knows by now that the scope of all that is desirable cannot be achieved through the efforts of one individual or even one school – enabling far-reaching desire for change to be more readily articulated. Only following on from the wider consideration of ‘what needs to change?’ does the teacher consider ‘how can I change?’ Whatever the teacher can and cannot yet do is understood as located within a wider politics. This does not diminish the ambitions of the action research planning that follows – but it connects the individual’s capacity to change with seeking to mobilize collective effort (Carr and Kemmis, 1986). Crucially, it mitigates against solution-oriented foundations for action research that restrict teachers to narrow goals that are easily achieved but do not change very much that is worth changing. At no stage do the cues invite the development of deficit analyses of students or teachers, but they introduce nuance, complexity and self-awareness in understanding the relationship of the teacher and the students with the current conditions. Having explored these issues, and the generative potential of values–practice dissonance, the action researcher is ready for the last stage (for now) and is invited to respond to the final cue, ‘what is this really about?’

Table 2 provides an example of how the framework has been typically applied to the equity issues raised by teachers who are concerned about students labelled ‘more able and talented’. It reflects the kinds of talk, questions and perceptions that have emerged through using such a framework in multiple contexts. It is a composite of multiple voices and reflects no individual teacher in particular, but it is rather a distillation of the core features that are explored.

| Stages | Examples of dialogue features | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | The concern | The teacher recounts a concern: students who are labelled as ‘more able and talented’ are not fulfilling their potential and sometimes appear to be bored or finish tasks quickly without exploring in depth. A story is told of a student who demonstrated this recently in their class. |

| 2. | Current state | Feelings of: professional inadequacy; lack of time to give students special attention in class; guilt; concern about parents’ evening conversations; awareness of students’ boredom. Beliefs that ability is fixed. Students who are high attaining cannot be fully catered for within the curriculum. The curriculum is sound. Something has to be done about this. Students should be ‘stretched’ to achieve higher scores. Students need an intervention that will stretch them. Awareness of other schools with special provision – after-school/dinner-time clubs for ‘able’ students. What other schools do seems to work. School leaders would like to see this. A likely solution would not be too difficult to organize and measure its effectiveness. |

| 3. | Perceived deficit | Some students are ‘too able’ for the curriculum. Students require something more than the curriculum can offer. |

| 4. | Systemic pressures | School data indicate that students categorized as ‘more able’ are not performing to predicted levels. School leaders and coordinator for ‘more able’ students want to see improvements. The inspection regime wants to see improved results. Parental expectations of provision for children categorized as ‘more able and talented’. Other schools showcasing schemes for ‘more able’ students. Competition among schools to attract ‘more able’ students. |

| 5. | Explore assumptions | What is wrong with the curriculum? What is it about the curriculum that is not fulfilling the needs of these students? Why is it OK to leave the curriculum alone? How do we know what it is like for other students to experience the curriculum? |

| 6. | Values and social justice | What values underpin the systemic pressures? What values underpin the teacher’s concern? What kinds of segregation are already in place? What are the risks of increasing segregation? What is being ignored that affects all students? What view of ‘ability’ is being perpetuated and what are the dangers? What are the risks of inequality of opportunity here? Who is being excluded from what? |

| 7. | What needs to change? | Curriculum is a major focus for change – how can that be achieved? Where can this start? How can students and colleagues share this task? This is not going to be straightforward. |

| 8. | How can I change? | Can I enrich learning experiences to include more student-led learning, open-ended exploration, self-regulation, student choice – for everybody? Can I work with students to think more about this concern? Can I do this slowly, choosing a place to start? I’m not sure I can take this on, but it would be wrong to ignore what I now think. Which colleagues will I talk with about this? |

| 9. | Revised concern for action research | This is about the need to develop a curriculum that is stimulating for all students. This will be harder than anticipated. This is bigger than anticipated. This cannot be the goal of an individual teacher. |

The example is a warning of the deeply unsettling impacts of increased consciousness of values–practice dissonance on teachers. In writing about his experiences of transformation through action research, Strauss (1995: 30) identified this as ‘professional schizophrenia’. His reflections on experiencing dissonance indicate the perpetual struggle that is at the heart of action research. He captures the dilemma of striving to increase social justice by teaching towards emancipatory goals for students, while being complicit with the performative agendas of schooling. It is hard to come to terms with and, ultimately, it is important to articulate profound self-awareness – ‘I am not the teacher I thought I was’. This is not to adopt a defeatist response to the challenge for the action researcher. Rather than locating this in a sense of individual deficit, action research directs these dilemmas towards the empowerment of teachers through increased collegiality, professional community and the collective commitment to worthwhile change.

Concluding remarks

In our collective experience, we have found that it is possible for teachers to avoid forms of action research that co-opt them into ‘proving’ that something works. It is possible to resist deficit analyses of students that distort the desire to do good. However, it has become increasingly difficult. Protocols for the deliberative exploration of the issues can help to reclaim action research as a disruptive practice, in which dissonance is highly valued and in which teachers can reassert socially just values as the basis for the change that is possible.

We have highlighted the need for conceptually derived tools that can provoke and deepen a professional dialogue that is able to challenge the dominant thinking that impacts on the ways schools are organized. Such thinking is deeply ingrained, and deliberative strategies are needed to fulfil the potential of action research to make things better. This is important from the beginning of thinking about the issues. The framework supports the importance of an incubation period that can challenge the ‘inherent danger’ of a simplistic emphasis on ‘cause and effect’ as a basis for research in classrooms (Evans et al., 2017). Most importantly, it relocates deficit thinking about students towards looking at the complexity of schools. This is something that is frequently difficult to achieve for those in a directed profession, where the emphasis on performativity reduces opportunities for critique and experimentation.

The dialogic process is particularly challenging in contexts where teachers have been ideologically co-opted into perpetuating the dominant discourses of normative, performance-oriented schooling that have oppressed educational aims for so long. Changing beliefs about what is good for learners and for society is, however, at the heart of action research. The crucial thing is to begin to talk in these ways. We can look to Kemmis for reassurance that the process of reaching deep understanding is an intentional struggle. We should have no illusions that action researchers can readily – or ever – achieve either uninterrupted space for talk like this, or achieve complete understanding of another person’s struggle. That, however, is not the point. Kemmis (2006: 473) argued:

The thing that holds a group together is the tacit or explicit agreement to continue the conversation towards these aims, despite the limits and interruptions – because there is no definite destination at which to arrive.

The crucial thing is to ‘open a communicative space’. The dialogic model we have developed is only the beginning of this process.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the teachers who engaged with versions of this model on the Master of Teaching (UCL Institute of Education), Master’s in Teaching and Learning (London Region), Master’s in Educational Practice (Cardiff University), at the Cardiff Festival 2018 and in workshops funded by an ESRC Impact Acceleration Award 2019–20.

Our thanks also go to Emmajane Milton and Alex Morgan (Cardiff University) for their work with teachers in Wales based on this model, enabled by funding from the Cardiff Festival and ESRC Impact Acceleration Award.

Notes on the contributors

Caroline Daly is Professor of Teacher Education at UCL Institute of Education and Associate Professor at the University of South Wales. She has worked extensively in the field of professional learning for early career teachers. Her research and development work is in mentoring early career teachers, professional learning and the school factors that affect the learning of new teachers. She is a Fellow of the International Professional Development Association.

Linda Davidge-Smith was a teacher and leader in primary schools for 22 years before moving into higher education where she has been Associate Head of School and Lecturer for Initial Teacher Education. She currently works at the University of South Wales and is a member of the Welsh Expert Group for Foundation Phase and the Foundation Phase Excellence Network. As Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy, she researches educative mentoring and pedagogical principles of effective learning and practice.

Chris Williams taught chemistry and was a pastoral leader in schools for over twenty years before working in higher education. He is currently Senior Lecturer in Secondary ITE at the University of South Wales. He completed his PhD at Swansea University prior to his career in teaching. He is particularly interested in research into holistic teaching methods that meet individual student development needs, as well as in developing educative mentoring for teaching professionals.

Catherine Jones is Head of Research Development and Pedagogic Practice in the School of Education, Early Years and Education and Education Cognate Research Group lead at the University of South Wales. Her research interests include developing professional practice, close-to-practice research collaboration and collaborative learning and blended learning. She has worked in partnership with schools and colleges on approaches to inquiry.

References

Ausubel, D.P. (1968). Educational Psychology: A cognitive view. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Ball, S. (2012). Politics and Policy Making in Education: Explorations in policy sociology. London: Routledge.

Bottery, M; Wright, N. (2000). Teachers and the State: Towards a directed profession. London: Routledge.

Brown, T; Rowley, H; Smith, K. (2015). The Beginnings of School-led Teacher Training: New challenges for university teacher education. Manchester: Manchester Metropolitan University.

Carr, W; Kemmis, S. (1986). Becoming Critical: Education, knowledge and action research. Geelong: Deekin University Press.

Carr, W; Kemmis, S. (2009). Educational action research: A critical approach In: Noffke, S, Somekh, B B (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Educational Action Research. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 74–84.

Cobb, P; Wood, T; Yackel, E. (1990). Classrooms as learning environments for teachers and researchers In: Davis, R, Mayer, C; C and Noddings, N N (eds.), Constructivist Views on the Teaching and Learning of Mathematics. Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, pp. 125–46.

Coghlan, D; Brannick, T. (2009). Doing Action Research in Your Own Organisation. 4th ed London: SAGE Publications.

Coldwell, M; Greany, T; Higgins, S; Brown, C; Maxwell, B; Stiell, B; Stoll, L; Willis, B; Burns, H. (2017). Evidence-Informed Teaching: An evaluation of progress in England: Research report. London: Department for Education. Online. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/625007/Evidence-informed_teaching_-_an_evaluation_of_progress_in_England.pdf . accessed 26 August 2020

Cordingley, P. (2014). Inquiry paper 5: The contribution of research to teachers’ professional development In: The Role of Research in Teacher Education: Reviewing the evidence. (Interim Report of the BERA-RSA Inquiry). London: British Educational Research Association, pp. 25–7.

Daly, C; Milton, E. (2017). External mentoring for new teachers: Mentor learning for a change agenda. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education 6 (3) : 178–95, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-03-2017-0021

Daly, C; Taylor, L. (2020). Teacher research in English classrooms: Questions that are worth asking? In: Davison, J, Daly, C C (eds.), Debates in English Teaching. London: Routledge, pp. 145–57.

Donaldson, G. (2015). Successful Futures: Independent review of curriculum and assessment arrangements in Wales. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

Door, V. (2014). Developing Creative and Critical Educational Practitioners. St Albans: Critical Publishing.

Estyn. Improving teaching. Cardiff: Estyn. Online. www.estyn.gov.wales/system/files/2020-07/Improving%2520teaching.pdf . accessed 26 August 2020

Evans, C; Waring, M; Christodoulou, A. (2017). Building teachers’ research literacy: Integrating practice and research. Research Papers in Education 32 (4) : 403–23, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2017.1322357

Fairclough, N. (1992). Critical Language Awareness. London: Longman.

Frost, D. (2012). From professional development to system change: Teacher leadership and innovation. Professional Development in Education 38 (2) : 205–27, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2012.657861

Grudnoff, L; Haigh, M; Jackson, C; Passfield, P. (2018). Using collaborative inquiry to examine equity-linked problems of practice. Set: Research Information for Teachers 2 : 33–9, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.18296/set.0107

Harris, A; Jones, M; Huffman, J. (2018). Teachers Leading Educational Reform: The power of professional learning communities. London: Routledge.

Hart, S; Dixon, A; Drummond, M; McIntyre, D. (2004). Learning without Limits. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Hipp, K; Huffman, J; Pankake, A; Olivier, D. (2008). Sustaining professional learning communities. Journal of Educational Change 9 : 173–95, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10833-007-9060-8

Holmlund Nelson, T; Deuel, A; Slavit, D; Kennedy, A. (2010). Leading deep conversations in collaborative inquiry groups. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas 83 (5) : 175–9, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00098650903505498

Hutchings, P; Shulman, L. (1999). The scholarship of teaching: New elaborations, new developments. Change 31 (5) : 10–15, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00091389909604218

Kemmis, S. (2006). Participatory action research and the public sphere. Educational Action Research 14 (4) : 459–76, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09650790600975593

Kools, M; Stoll, L. (2016). What Makes a School a Learning Organisation? A guide for policy makers, school leaders and teachers. Paris: OECD.

Lawton-Sticklor, N; Bodamer, S. (2016). Learning to take an inquiry stance in teacher research: An exploration of unstructured thought-partner spaces. The Educational Forum 80 (4) : 394–406, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2016.1206161

McNiff, J. (2002). Action research for professional development, Online. www.jeanmcniff.com/ar-booklet.asp . accessed 26 August 2020

OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). Developing Schools as Learning Organisations in Wales. (Implementing Education Policies). Paris: OECD, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/9789264307193-en

Pearl, A. (1997). Democratic education as an alternative to deficit thinking In: Valencia, R.R (ed.), The Evolution of Deficit Thinking: Educational thought and practice. London: Falmer Press, pp. 211–41.

Pedder, D; James, M; MacBeath, J. (2005). How teachers value and practise professional learning. Research Papers in Education 20 (3) : 209–43, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02671520500192985

Pedder, D; Opfer, V.D. (2013). Professional learning orientations: Patterns of dissonance and alignment between teachers’ values and practices. Research Papers in Education 28 (5) : 539–70, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2012.706632

Philpott, C; Poultney, V. (2018). Evidence-Based Teaching: A critical overview for enquiring teachers. St Albans: Critical Publishing.

Poultney, V. (2019). Different schools, same problem: What value teacher research and inquiry, BERA blog, 11 February. Online. www.bera.ac.uk/blog/different-schools-same-problem-what-value-teacher-research-and-inquiry . accessed 26 August 2020

Ritter, M; Dijksterhuis, A. (2014). Creativity – the unconscious foundations of the incubation period. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience 8 (Article 215) : 1–10, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2014.00215

Rüschoff, B; Ritter, M. (2001). Technology-enhanced language learning: Construction of knowledge and template-based learning in the foreign language classroom. Computer Assisted Language Learning 14 (3–4) : 219–32, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1076/call.14.3.219.5789

Sahlberg, P. (2011). Finnish Lessons: What can the world learn from educational change in Finland. New York: Teachers College Press.

Sio, U.N; Ormerod, T.C. (2009). Does incubation enhance problem solving? A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin 135 (1) : 94–120, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014212

Soultana, M; Stamatina, B. (2013). Collaborative action research projects: The role of communities of practice and mentoring in enhancing teachers’ continuing professional development. Action Researcher in Education 4 : 109–21.

Stenhouse, L. (1975). An Introduction to Curriculum Research and Development. London: Heinemann.

Stenhouse, L. (1980). Curriculum Research and Development in Action. London: Heinemann.

Strauss, P. (1995). No easy answers: The dilemmas and challenges of teacher research. Educational Action Research 3 (1) : 29–40, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0965079950030103

Thomson, P. (2015). Action research with/against impact. Educational Action Research 23 (3) : 309–11, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2015.1062235

Tripp, D. (1993). Critical Incidents in Teaching: Developing professional judgement. London: Routledge.

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). Accountability in Education: Meeting our commitments. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Online. https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/report/2017/accountability-education . accessed 26 August 2020

Welsh Assembly Government. School Effectiveness Framework. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government.

Welsh Government. Professional Learning Communities. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

Welsh Government. Professional Learning Communities. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

Wheatley, K. (2002). The potential benefits of teacher efficacy doubts for educational reform. Teaching and Teacher Education 18 (1) : 5–22, Online. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(01)00047-6